0593

MR Imaging Deep Brain Stimulation of the Nucleus Basalis Meynert Restored Cognitive Function in Alzheimer’s Disease Model1Department of Biomedical Engineering, National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University, Taipei, Taiwan, 2Biomedical Translation Research Center, Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan, 3Ph.D. Program in Medical Neuroscience, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan, 4Department of Neurology, Buddhist Tzu Chi Medical Foundation, Hualien, Taiwan, 5Department of Neurology, Tzu Chi University, Hualien, Taiwan

Synopsis

Keywords: Neurodegeneration, fMRI, Nucleus Basalis of Meynert

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is an intricate neurodegenerative disease. Nucleus Basalis of Meynert (NBM), a key region of the cholinergic system that provides acetylcholine to cortex, has been shown to be target for deep brain stimulation (DBS) in AD. The 5×FAD mouse model was used to investigate the change of behavioral tasks, resting-state functional MRI, and acetylcholinesterase (AChE) assay were applied in this study. We found that NBM-DBS may play an important role in modulating cognitive function and spatial working memory in 5×FAD mice. Increasing functional connectivity and decreasing AChE activity may be the biomarkers for AD individuals.Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is an intricate neurodegenerative disease with a combination of multiple factors1. There are several hypotheses concerning the origin of AD2,3. The cholinergic hypothesis describes the symptom onset because of a reduced acetylcholine synthesis4-7. Previous research has linked cholinergic neurotransmitter system disruption to cognitive, emotional, and behavioral symptoms of AD8. The nucleus Basalis of Meynert (NBM) is a key region of the cholinergic system, which provides the major acetylcholine (Ach) to the cortex9-11. Additionally, a strong correlation had been shown between NBM neural loss, resultant cortical cholinergic deficits, and cognitive impairment in AD12-14. Besides, the Ach is degraded to choline and acetic acid by the enzyme acetylcholinesterase (AChE)15,16. In this study, we applied deep brain stimulation (DBS) of NBM induced changes in functional connectivity (FC) and AChE activity, corresponding to cognitive function and spatial working memory. We hypothesized that NBM-DBS may change the FC and AChE activity, improving the behavioral performance in the 5×FAD mouse model.Methods

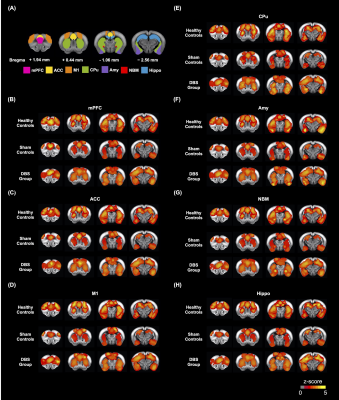

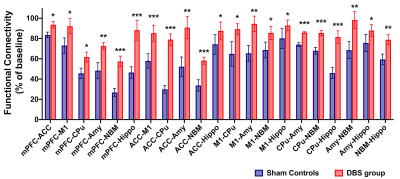

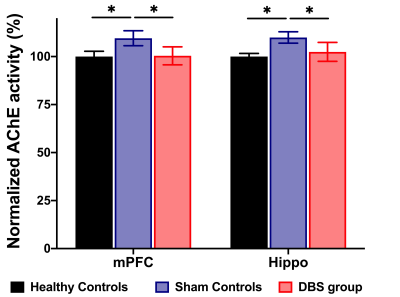

Adult male C57BL/6 mice (weight 20 ± 5 g, N = 10) were used as the healthy controls, and adult male 5×FAD mice (weight 20 ± 5 g, N = 20) were used as the sham controls and DBS group. All groups were housed in the animal facility under a 12:12-h light/dark cycle with a controlled temperature of 22 ± 2°C. The mice were allowed to recover for 7 days after the neural probe implantation surgery in bilateral NBM (AP: -1.06 mm, ML: ± 2.00 mm, DV: - 4.20 mm). Implanted mice in three groups were placed in a plastic cage (30 cm diameter and 38 cm height) for 30 min/day with/without DBS (duration: 20 sec, biphasic electrical current: 200 𝝁A, pulse width: 60 𝝁s, frequency: 130Hz), and then performed the behavioral tasks. Novel object recognition (NOR) task over three days (habituation, training, and testing) to evaluate the rodents' ability to recognize a novel object in their environment. A preference index (PI) was computed using the formula: PI = (n) / (n+f), where n represents time spent with novel objects and f represents time spent with familiar objects. The T-maze was used to assess spatial working memory for five days, with one session per day and five trials per session. The latency time to reach the correct T-maze goal arm was plotted against the session. To investigate the FC alteration with NBM-DBS, brain images were obtained using a Bruker 7 Tesla magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanner (Bruker Biospec 70/30 USR, Ettlingen, Germany). The gradient-echo planar imaging (GE-EPI) sequence (TR = 2,000 ms, TE = 20 ms, FOV = 20 × 20 mm2, matrix size = 80 × 80, bandwidth = 200 kHz, 14 coronal slices, and thickness = 0.5 mm) was used to obtain the resting-state functional MRI (rsfMRI) images. There were 260 dynamics for 10 dummy scans and 250 rsfMRI images in the GE-EPI images. The FMRIB Software Library v5.0 (FSL 5.0; www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl) and the Analysis of Functional NeuroImages (AFNI) software (http://afni.nimh.nih.gov/afni) were used to perform a ROI-based analysis of FC between regions such as the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), motor cortex (M1), amygdala (Amy), caudate putamen (CPu), NBM, and hippocampus (Hippo). The Allen mouse brain 17 ROIs were also resliced to match the affined GE-EPI datasets in dimension. To compare the FC caused by NBM-DBS quantitatively, the measured FC between distinct brain areas was normalized. The mPFC and Hippo were dissected from the brain tissues to detect the AChE activity by acetylcholinesterase assay kit (ab138871, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) which applied by a modified Ellman method18.Results

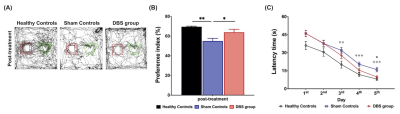

In the behavioral tasks, PI in healthy controls and DBS group were significantly higher than sham controls (Figure 1.(A),(B)). The latency time to reach the criterion was significantly shorter in healthy controls compared to sham controls from 3rd to 5th day, and significantly shorter than sham controls on 5th day in the DBS group (Figure 1.(C)). Additionally, the normalized FC in DBS group presented the enhancement compared with sham controls (Figure 2. and Figure 3.). Furthermore, while compared with healthy controls and the DBS group, sham controls had higher normalized AChE activity in the mPFC and Hippo (Figure 4.).Discussion

We found the NBM-DBS enhanced the FC, improved the performance of behavioral tasks related to cognitive function and spatial working memory, and decreased the AChE activity in mPFC and Hippo in AD model. In previous study, the mechanism of DBS has focus on the modulation of brain networks19-22, and DBS in cortical-NBM pathway reduce the performance in learning and memory23-26. Inhibiting AChE activity can ameliorate the availability of Ach to enhance the cholinergic neurotransmission relate to cognitive function and memory27,28.Conclusion

In this study, we applied the NBM-DBS in the 5×FAD mice model, demonstrating the differences in behavioral performance, FC, and AChE activity in healthy controls, sham controls, and DBS group. Our findings support the importance of NBM as a therapeutic target for improving cognitive function and memory in AD individuals.Acknowledgements

This work is financially supported by the National Science and Technology Council under Contract numbers of MOST 111-2321-B-A49-005-, 111-2314-B-303-026-, 111-2221-E-A49-049-MY2, 111-2314-B-038-059-MY3. Partial support for the work also is provided by the “Key and Novel Therapeutics Development Program for Major Diseases” project of Academia Sinica, Taiwan, R.O.C. under Grant number AS-KPQ-111-KNT.

References

1. Scheltens P, De Strooper B, Kivipelto M, et al. Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet (London, England). 2021;397(10284):1577.

2. Cheng Y-J, Lin C-H, Lane H-Y. Involvement of cholinergic, adrenergic, and glutamatergic network modulation with cognitive dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021;22(5):2283.

3. Ju Y, Tam KY. Pathological mechanisms and therapeutic strategies for Alzheimer’s disease. Neural Regeneration Research. 2022;17(3):543.

4. Francis PT, Palmer AM, Snape M, Wilcock GK. The cholinergic hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: a review of progress. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 1999;66(2):137-147.

5. Terry AV, Buccafusco JJ. The cholinergic hypothesis of age and Alzheimer's disease-related cognitive deficits: recent challenges and their implications for novel drug development. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2003;306(3):821-827.

6. Coyle JT, Price DL, Delong MR. Alzheimer's disease: a disorder of cortical cholinergic innervation. Science. 1983;219(4589):1184-1190.

7. Chen Z-R, Huang J-B, Yang S-L, Hong F-F. Role of Cholinergic Signaling in Alzheimer’s Disease. Molecules. 2022;27(6):1816.

8. Klaassens BL, van Gerven JM, Klaassen ES, van der Grond J, Rombouts SA. Cholinergic and serotonergic modulation of resting state functional brain connectivity in Alzheimer's disease. NeuroImage. 2019;199:143-152.

9. Mesulam M-M, Mufson EJ, Levey AI, Wainer BH. Cholinergic innervation of cortex by the basal forebrain: Cytochemistry and cortical connections of the septal area, diagonal band nuclei, nucleus basalis (Substantia innominata), and hypothalamus in the rhesus monkey. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1983;214(2):170-197.

10. Gratwicke J, Kahan J, Zrinzo L, et al. The nucleus basalis of Meynert: a new target for deep brain stimulation in dementia? Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2013;37(10):2676-2688.

11. Laxton AW, Lipsman N, Lozano AM. Deep brain stimulation for cognitive disorders. In: Handbook of clinical neurology. Vol 116. Elsevier; 2013:307-311.

12. Etienne P, Robitaille Y, Wood P, Gauthier S, Nair N, Quirion R. Nucleus basalis neuronal loss, neuritic plaques and choline acetyltransferase activity in advanced Alzheimer's disease. Neuroscience. 1986;19(4):1279-1291.

13. Gilmor ML, Erickson JD, Varoqui H, et al. Preservation of nucleus basalis neurons containing choline acetyltransferase and the vesicular acetylcholine transporter in the elderly with mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1999;411(4):693-704.

14. Candy J, Perry R, Perry E, et al. Pathological changes in the nucleus of Meynert in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases. Journal of the neurological sciences. 1983;59(2):277-289.

15. Massoulié J, Pezzementi L, Bon S, Krejci E, Vallette F-M. Molecular and cellular biology of cholinesterases. Progress in Neurobiology. 1993;41(1):31-91.

16. Peng L, Rong Z, Wang H, et al. A novel assay to determine acetylcholinesterase activity: The application potential for screening of drugs against Alzheimer's disease. Biomedical Chromatography. 2017;31(10):e3971.

17. Lein ES, Hawrylycz MJ, Ao N, et al. Genome-wide atlas of gene expression in the adult mouse brain. Nature. 2007;445(7124):168-176.

18. Ellman GL. A colorimetric method for determining low concentrations of mercaptans. Archives of biochemistry and Biophysics. 1958;74.2:443-450.

19. Li S-J, Lo Y-C, Lai H-Y, et al. Uncovering the Modulatory Interactions of Brain Networks in Cognition with Central Thalamic Deep Brain Stimulation Using Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Neuroscience. 2020;440:65-84.

20. McIntyre CC, Hahn PJ. Network perspectives on the mechanisms of deep brain stimulation. Neurobiology of Disease. 2010;38(3):329-337.

21. Montgomery EB, Gale JT. Mechanisms of action of deep brain stimulation (DBS). Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2008;32(3):388-407.

22. Miocinovic S, Somayajula S, Chitnis S, Vitek JL. History, Applications, and Mechanisms of Deep Brain Stimulation. JAMA Neurology. 2013;70(2):163-171.

23. Montero-Pastor A, Vale-Martı́nez A, Guillazo-Blanch G, Nadal-Alemany R, Martı́-Nicolovius M, Morgado-Bernal I. Nucleus basalis magnocellularis electrical stimulation facilitates two-way active avoidance retention, in rats. Brain research. 2001;900(2):337-341.

24. Montero-Pastor A, Vale-Martı́nez A, Guillazo-Blanch G, Martı́-Nicolovius M. Effects of electrical stimulation of the nucleus basalis on two-way active avoidance acquisition, retention, and retrieval. Behavioural brain research. 2004;154(1):41-54.

25. Chen Y-s, Shu K, Kang H-c. Deep Brain Stimulation in Alzheimer’s Disease: Targeting the Nucleus Basalis of Meynert. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 2021(Preprint):1-18.

26. Gratwicke J, Oswal A, Akram H, et al. Resting state activity and connectivity of the nucleus basalis of Meynert and globus pallidus in Lewy body dementia and Parkinson's disease dementia. NeuroImage. 2020;221:117184.

27. Pan H, Zhang J, Wang Y, et al. Linarin improves the dyskinesia recovery in Alzheimer's disease zebrafish by inhibiting the acetylcholinesterase activity. Life Sciences. 2019;222:112-116.

28. Blokland A. Acetylcholine: a neurotransmitter for learning and memory? Brain Research Reviews. 1995;21(3):285-300.

Figures

Figure 1. (A) The trajectory of testing day in healthy controls, sham controls, and AD group (red: previous object, green: novel object). (B) The preference index had significantly lower in sham controls than in healthy controls and DBS group. (C) Curves of latency time (s) to reach the correct T-maze goal arm. There were significantly shorter learning periods found in healthy controls from the 3rd to the 5th day, and DBS group on the 5th day compared with sham controls.

* indicated significant differences with p < 0.05, and the data were analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis test (Mean ± SEM).