0587

The interaction between first-episode schizophrenia and age based on gray matter volume and its molecular analysis: A multimodal MRI study1Department of Magnetic Resonance Imaging, The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, China, 2Laboratory for Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Molecular Imaging of Henan Province, Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Zhengzhou, China

Synopsis

Keywords: Neurodegeneration, Gray Matter, gray matter volume / early-onset schizophrenia / adult-onset schizophrenia /neurodevelopment / visual perception / visual cognitive

We aimed to investigate the interaction characteristics of schizophrenia and onset age and its underlying molecular mechanisms by using T1-weighted high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging (3DT1) and the JuSpace toolbox. 150 first-episode drug-naïve schizophrenia and 119 matched normal controls were recruited and underwent 3DT1 scans. Our results show that the two main effects of factors and interaction effect in gray matter volume and their underlying molecular mechanisms have varying degrees of specificity changes. Particularly, the abnormality of the visual perception system and higher visual cognitive functions in early-onset schizophrenia (EOS) have guiding significance for the mechanism and treatment of EOS.Introduction

Early-onset schizophrenia (EOS: onset after the age of 18) is thought to be clinically and neurobiologically continuous with adult-onset schizophrenia (AOS: onset 13–18 years), with a poor outcome and high severity, increased genetic vulnerability, and a 12.3% prevalence1-3. Differences in the age of onset of schizophrenia may explain the inconsistent findings and the heterogeneity of the disorder itself4, 5. According to the well-known neurodevelopmental hypothesis, schizophrenia starts early in the process of brain development and gradually leads to dynamic structural abnormalities of the brain6. Therefore, understanding the impact of developmental status on pathological processes involving brain structures in schizophrenia is crucial to comprehend the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Moreover, neurotransmitters are involved in a variety of developmental processes, including neuronal proliferation, differentiation, and the process of apoptosis, in addition to their primary role in regulating synaptic communication7, 8. And, the gray matter density on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is an indirect indicator of the intricate architecture of glia, vasculature, and neurons with dendritic and synaptic processes9. Previous studies have generally used longitudinal data on schizophrenia to study the effects of development on schizophrenia, but data from such studies are relatively difficult to collect. Our study uses cross-sectional data in an interactive manner to investigate the effect of the age-onset of schizophrenia on gray matter volume (GMV) and to explore the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms in conjunction with molecular structural abnormalities.Materials and Methods

FES patients (84 AOS and 66 EOS) and NC (73 adults and 46 adolescents) were included in this study. All participants were scanned using 3.0 T MRI scanner with 8-channel receiver array head coil (Discovery MR750, GE, USA). Spatial-3D high-resolution T1-weighted images (3DT1) were acquired using a brain volume sequence with the following settings: repetition time/echo time = 8.2/3.2 ms, slice thickness = 1 mm, slice gap = 0 mm, flip angle = 12°, slice number = 1, field of view (FOV) = 25.6 × 25.6 cm2, number of averages = 1, matrix size = 256 × 256, voxel size = 1 × 1 ×1 mm3. Voxel-based morphometry analyses were preprocessed with the Computational Anatomy Toolbox, a software extension to the Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM12). Processing steps include image evaluation, normalization, segmenting, resampling, and smoothing. And, using the JuSpace toolkit (Dukart et al., 2021), we evaluated the spatial correlation between the GMV difference map (interaction effect, main effects) and positron emission tomography/single photon computed emission tomography (PET/SPECT) maps to examine if there was a link between factors-induced alterations in GMV and neurotransmitter expression. For GMV comparisons, two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to examine the main effect of the diagnosis (schizophrenia vs. controls) and age (adolescent vs. adults) and their interaction effects between diagnosis and age. Multiple comparisons were corrected according to the Gaussian random field (GRF) theory (voxel-wise P < 0.001, cluster-wise P < 0.05, two-tail, and cluster extent threshold at k > 30). Post hoc comparisons were used by Mann-Whitney (P < 0.05/2 for main effect analyses, P < 0.05/4 for interaction effect analyses, Bonferroni-corrected). Furthermore, a correlation analysis between clinical measures and significant outcomes between groups was performed by Spearman's rank correlation.Results

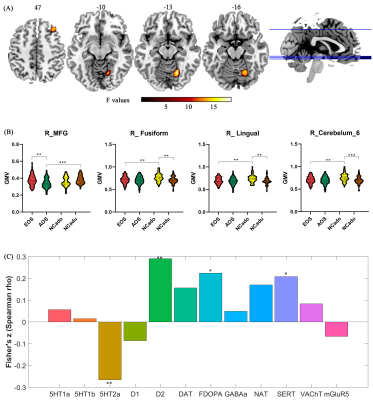

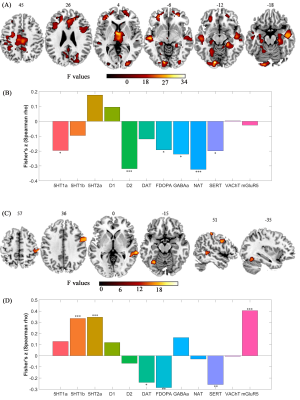

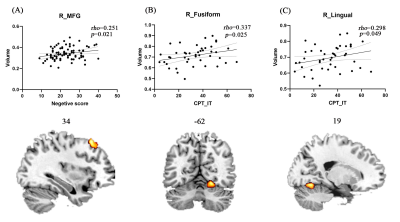

Compared to AOS, EOS and adult NC had larger GMV in right middle frontal gyrus. Compared to adolescent NC, EOS and adult NC had smaller GMV in right lingual gyrus, right fusiform gyrus, and right cerebellum_6 (Figure 1). Disease-induced GMV reductions were mainly distributed in frontal, parietal, thalamus, visual, motor cortex, and medial temporal lobe structures (Figure 2.). Age-induced GMV alterations were mainly distributed in visual and motor cortex (Figure 2). The changed GMV induced by schizophrenia, age, and their interaction were related to dopaminergic and serotonergic receptors. Age is also related to glutamate receptors, and schizophrenia is also associated with (GABAa)ergic and noradrenergic receptors (Figure 2). Correlation analysis showed that the GMV reduction of the right MFG in AOS was positively correlated with the negative score (P = 0.021, rho = 0.251), and the GMV reduction in the right fusiform gyrus and the right lingual gyrus of EOS was positively correlated with the CPT_IT score, respectively (P = 0.025, rho = 0.337; P = 0.049, rho = 0.298) (Figure 3).Discussion and conclusion

The current findings suggest that disruptions in visual perceptual system and abnormalities in higher visual cognitive functions in EOS and their underlying molecular mechanisms were influenced by developmental status, which may provide clues for early intervention in EOS.Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the individuals who participated in this study. We also express our gratitude to the technical staff of the Magnetic Resonance Department of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, who helped to acquire images of patients, and the staff of the Department of Psychiatry of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University. And, all authors declared no conflict of interest.References

1. Diaz-Caneja CM, Pina-Camacho L, Rodriguez-Quiroga A, Fraguas D, Parellada M, Arango C. Predictors of outcome in early-onset psychosis: a systematic review. NPJ Schizophr 2015;1:14005.

2. Ahn K, An SS, Shugart YY, Rapoport JL. Common polygenic variation and risk for childhood-onset schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry Jan 2016;21(1):94-96.

3. Arango C, Buitelaar JK, Correll CU, et al. The transition from adolescence to adulthood in patients with schizophrenia: Challenges, opportunities and recommendations. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol Jun 2022;59:45-55.

4. Zhang C, Wang Q, Ni P, et al. Differential Cortical Gray Matter Deficits in Adolescent- and Adult-Onset First-Episode Treatment-Naive Patients with Schizophrenia. Sci Rep Aug 31 2017;7(1):10267.

5. Gogtay N, Vyas NS, Testa R, Wood SJ, Pantelis C. Age of onset of schizophrenia: perspectives from structural neuroimaging studies. Schizophr Bull May 2011;37(3):504-513.

6. Rapoport JL, Giedd JN, Gogtay N. Neurodevelopmental model of schizophrenia: update 2012. Mol Psychiatry Dec 2012;17(12):1228-1238.

7. Xing L, Huttner WB. Neurotransmitters as Modulators of Neural Progenitor Cell Proliferation During Mammalian Neocortex Development. Front Cell Dev Biol 2020;8:391.

8. Heather A. Cameron TGH, Ronald D. G. McKay. Regulation of Neurogenesis by Growth Factors and Neurotransmitters. Journal of Neurobiology 1998;31.

9. Nitin Gogtay*† JNG, Leslie Lusk*, Kiralee M. Hayashi‡, Deanna Greenstein*,A. Catherine Vaituzis*, Tom F. Nugent III*, David H. Herman*, Liv S. Clasen*, Arthur W. Toga‡, Judith L. Rapoport*, and Paul M. Thompson‡. Dynamic mapping of human cortical development during childhood through early adulthood. PNAS 2004;101.

Figures