0586

Distinct patterns of microstructural changes in mouse models of ALS/FTD with mutations in Tardbp, Fus and C9orf721Wellcome Centre for Integrative Neuroimaging, FMRIB, Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom, 2UK Dementia Research Institute at UCL, Faculty of Brain Sciences, University College London, London, United Kingdom, 3Department of Neurodegenerative Disease, UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology, University College London, London, United Kingdom, 4Mouse Imaging Centre, The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, ON, Canada, 5Department of Physiology, Anatomy and Genetics, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom, 6Mammalian Genetics Unit, MRC Harwell Institute, Oxford, United Kingdom, 7MRC Prion Unit and Institute of Prion diseases, University College London, London, United Kingdom, 8Department of Neuromuscular Diseases, UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology, University College London, London, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: Neurodegeneration, Preclinical

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) form a disease spectrum with shared clinical, pathological and genetic features. The most common mutations in ALS/FTD are in the genes C9Orf72, TARDBP and FUS. We used post-mortem diffusion kurtosis imaging to assess microstructure imaging phenotypes in mouse models of ALS/FTD with mutations in these genes. While mice with mutation in Tardbp presented reduced FA and MO in various white matter tracts, no difference could be detected in mice with mutation in Fus, and increased MO in a portion of the corpus callosum was observed in mice with mutation in C9orf72.Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) form a disease spectrum with shared clinical, pathological and molecular features1. ALS patients present mainly motor defects, while FTD patients have changes in executive function, language and behaviour. Approximately 50% of ALS patients present behavioural and cognitive impairment and ~40% of FTD patients develop motor dysfunction2. More than 30 genes are causative for ALS1, of which at least 17 genes are linked to ALS and FTD2. The most common genetic mutations in ALS and FDT are in C9Orf72, TARDBP, and FUS genes2.The disease mechanisms in ALS/FTD are not fully understood and these diseases lack a cure or treatment. Animal models that recapitulate features of ALS/FTD are essential to better understand disease mechanisms and assess potential therapeutics. Due to the heterogeneous nature of ALS/FTD, a range of animal models may be needed to better represent the ALS/FTD subgroups3.

MRI can provide biomarkers of ALS/FTD and contribute to the understanding of disease mechanisms and the development of candidate therapies. Imaging signatures of FTD/ALS include cortical thinning4, atrophy of subcortical grey matter5, and altered diffusion-MRI metrics6, varying according to the gene involved7. Despite the numerous animal models of ALS/FTD, most imaging studies focus on the SOD1 mouse, which is only representative of 2% of ALS cases8. In this study, we explore post-mortem diffusion MRI phenotypes in a broader range of mouse models of ALS/FTD with mutations in the genes Tardbp, Fus, and C9orf72.

Materials and methods

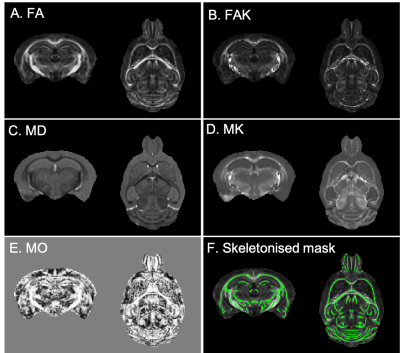

In total, 59 mice divided into three cohorts were studied. Mice had mutations in Tardbp (TDP-M323K9: 8 TDP-M323K homozygous mutants, 8 wild-type (WT) littermates, 12 month-old), Fus (homozygous FUSDelta1410,11: 7 FUSDelta14 homozygous mutants, 10 WT littermates, 3-month-old), or C9orf72 (9 C9orf72-(PR)400 expressing PR dipeptide repeats12, 7 C9orf72-(GR)400 expressing GR dipeptide repeats12, and 10 WT littermates, 20 month-old). Ages were selected to reflect advanced stages of the disease in each model. Mice were perfused with paraformaldehyde 4% in 0.1 M PBS under anaesthesia. Perfusion solutions contained 2 mM of Gd-contrast agent (Gd-CA, Gadovist, Bayer Vital GmbH, Leverkusen, Germany). Heads were removed and dissected, keeping brains in the skull. Brains were immersed in 4% paraformaldehyde with 2 mM Gd-CA for 24h at 4oC, and then kept in PBS with 2 mM Gd-CA and 0.05% azide at 4oC until scanned.Diffusion MRI was performed on a 7.0 tesla MRI scanner using a receive-only 4-channels surface cryoprobe and a volume transmit resonator (Bruker Biosystems, Etlingen, Germany). Diffusion-weighted images were acquired in 30 diffusion directions distributed across the sphere for 2 shells (b=2,500/10,000s/mm2), with four interleaved b=0 volumes (segmented EPI, TE/TR=30/500ms, 12 segments, 100μm isotropic resolution, scan time~12h). A separated b=0 volume with reversed phase encoding was acquired prior to the diffusion-weighted images and allowed to correct off-resonance effects using the package eddy13 (after Gibbs ringing correction14). Signal was fitted with the diffusion kurtosis model using FSL15 dtifit with the --kurtdir option to estimate fractional anisotropy (FA), mean diffusivity (MD), mode of anisotropy16 (MO), and kurtosis along parallel and perpendicular directions. Parallel and perpendicular kurtosis were then used to extract mean kurtosis (MK), and fractional anisotropy of kurtosis (FAK) (Figure 1, A-E).

Data was analysed separately for each cohort (TDP-M323K, FUSDelta14 and C9orf72). The b=0 images from each animal were averaged and the average b0 images were registered to a common space using pydpiper17. The same transforms were used to register all parametric maps to the common space for each cohort. FA maps were averaged, thresholded to include only voxels with FA above 0.3, and then skeletonised using FSL-TBSS18 to create a skeletonised white matter mask (Figure 1, F). For each parametric map, voxels extracted with this mask were compared between mutant mice and age-matched littermates using FSL-randomise19. Differences were considered significant for p<0.05 after family-wise error (FWE) correction for multiple comparisons in each metric.

Results

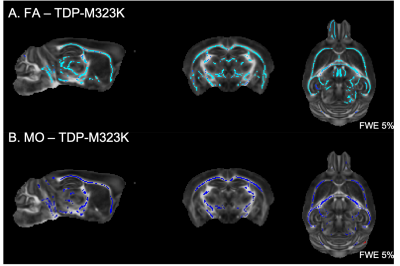

Multiple white matter tracts presented reduced FA and reduced MO in TDP-M323K mice (Figure 2). No differences could be detected in MD, MK, or FAK.In this study, no differences could be detected in white matter for any of the diffusion MRI metrics assessed in homozygous FUSDelta14 mice.

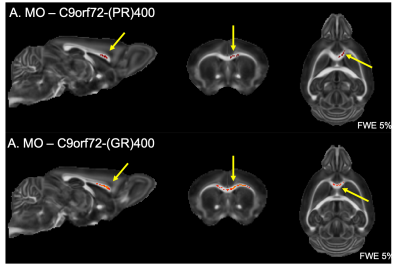

Finally, both C9orf72-(GR)400 and C9orf72-(PR)400 mice presented reduced MO in the anterior portion of the corpus callosum (Figure 3). No further alteration could be detected for FA, MD, MK or FAK in these mice.

Discussion and conclusions

We have previously described that the pattern of volumetric changes is different in TDP-M323K, FUSDelta14 and C9Orf72-PR(400)/-GR(400) mice12 (Figure 4). In this study, we showed that in addition to widespread volumetric changes20, TDP-M323K mice also present reduced FA and MO in several white matter tracts. In contrast, FUSDelta14-hom mice, which present volumetric changes affecting various brain regions11, did not show any detectable alteration in white matter microstructure in the current study. Finally, C9orf72-(PR)400 and C9orf72-(GR)400 mice presented subtle changes in MO in the anterior portion of the corpus callosum. This region is close to the taenia tecta, the only structure where altered volume was observed in these animals12. These results expand the range of mouse models of ALS/FTD with microstructural alterations assessed with MRI and reinforce the complementarity of structural and diffusion MRI.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust (grant 202788/Z/16/Z), MRC and Harwell funding. The Wellcome Centre for Integrative Neuroimaging is supported by core funding from the Wellcome Trust (grant 203139/Z/16/Z).References

1. van Es, M. A. et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet 390, 2084–2098 (2017).

2. Gelon, P. A., Dutchak, P. A. & Sephton, C. F. Synaptic dysfunction in ALS and FTD: anatomical and molecular changes provide insights into mechanisms of disease. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 15, (2022).

3. Stephenson, J. & Amor, S. Modelling amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in mice. Drug Discov. Today Dis. Model. 25–26, 35–44 (2017).

4. Verstraete, E. et al. Structural MRI reveals cortical thinning in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 83, 383–388 (2012).

5. Westeneng, H.-J. et al. Subcortical structures in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurobiol. Aging 36, 1075–1082 (2015).

6. Christidi, F. et al. Gray matter and white matter changes in non-demented amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients with or without cognitive impairment: A combined voxel-based morphometry and tract-based spatial statistics whole-brain analysis. Brain Imaging Behav. 12, 547–563 (2018).

7. Spinelli, E. G. et al. Structural MRI Signatures in Genetic Presentations of the Frontotemporal Dementia/Motor Neuron Disease Spectrum. Neurology 97, E1594–E1607 (2021).

8. Bonifacino, T. et al. Nearly 30 Years of Animal Models to Study Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Historical Overview and Future Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 12236 (2021).

9. Fratta, P. et al. Mice with endogenous TDP‐43 mutations exhibit gain of splicing function and characteristics of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. EMBO J. 37, e98684 (2018).

10. Devoy, A. et al. Humanized mutant FUS drives progressive motor neuron degeneration without aggregation in ‘FUSDelta14’ knockin mice. Brain 140, 2797–2805 (2017).

11. Martins-Bach, A. B. et al. Brain structure in the homozygous FUSDelta14 mouse recapitulates amyotrophic lateral sclerosis phenotypes. in Proc. Intl. Soc. Mag. Reson. Med. 28 (2020).

12. Martins-Bach, A. B. et al. Mild neuroanatomical phenotype in an ALS mouse model with mutation in C9orf72. in Proc. Intl. Soc. Mag. Reson. Med.31 (2022).

13. Andersson, J. L. R. & Sotiropoulos, S. N. An integrated approach to correction for off-resonance effects and subject movement in diffusion MR imaging. Neuroimage 125, 1063–1078 (2016).

14. Kellner, E., Dhital, B., Kiselev, V. G. & Reisert, M. Gibbs-ringing artifact removal based on local subvoxel-shifts. Magn. Reson. Med. 76, 1574–1581 (2016).

15. Smith, S. M. et al. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. Neuroimage 23, 208–219 (2004).

16. Ennis, D. B. & Kindlmann, G. Orthogonal tensor invariants and the analysis of diffusion tensor magnetic resonance images. Magn. Reson. Med. 55, 136–46 (2006).

17. Nieman, B. J. et al. MRI to Assess Neurological Function. Curr. Protoc. Mouse Biol. 8, e44 (2018).

18. Smith, S. M. et al. Tract-based spatial statistics: Voxelwise analysis of multi-subject diffusion data. Neuroimage 31, 1487–1505 (2006).

19. Winkler, A. M., Ridgway, G. R., Webster, M. A., Smith, S. M. & Nichols, T. E. Permutation inference for the general linear model. Neuroimage 92, 381–397 (2014).

20. Martins-Bach, A. B. et al. Anatomical and microstructural brain alterations in the TDP-M323K mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. in Proc. Intl. Soc. Mag. Reson. Med. 29 (2021).

Figures