0572

Realizing sub-second and sub-millimeter spinal cord fMRI at 7 Tesla1Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Charlestown, MA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Spinal Cord, fMRI (resting state)

Spinal cord fMRI is an emerging field with clinical potential. Sub-millimeter in-plane fMRI acquisitions are desirable and achievable, but published studies have had modest temporal resolutions (>2s). Using a custom-built 7T spine coil, we demonstrate sub-second and sub-millimeter cervical cord fMRI for the first time. Employing a 3D multi-shot sequence with appropriate phase corrections and NORDIC denoising, our data demonstrated temporal signal-to-noise ratios similar to those of standard supra-second protocols, and we replicated functional connectivity patterns previously published in the cord. This opens new avenues of discovery similar to those realized through high spatiotemporal resolution brain fMRI.Introduction

Investigating spinal cord function using fMRI is relevant for neurological diseases such as multiple sclerosis1 and pain2, and fundamental/clinical advancements have been made over the past decade (e.g.,3–9). In spinal cord fMRI, voxel sizes of ≤1mm (in-plane) are essentially required because the cord is narrow, and gray matter horns have dimensions of only 1-3mm. Spinal cord imaging at 7T is advantageous for high resolution fMRI, but prior studies have had to compromise on the temporal resolution to meet other constraints of spatial resolution and coverage, resulting in a volume acquisition time (VAT) over 2s. In the brain, fMRI investigations with sub-second sampling rates have demonstrated the unique benefits of high temporal resolution fMRI10. For instance, dynamic connectivity architecture is revealed with better precision11 and certain faster neural processes are discoverable only at sub-second resolutions12. We posit that future spinal cord fMRI research will similarly benefit from sub-second and sub-millimeter acquisitions (SSSM).Achieving SSSM is, however, not trivial. Spinal cord fMRI is challenging with higher physiological noise due to the closer proximity to moving organs (tongue, throat, heart, lungs), and distortions arising from dynamic B0 inhomogeneities13. Although achieving SSSM is more feasible at 7T, these noise sources/distortions are also amplified at 7T. Our prior work at 7T suggests that a 3D multi-shot sequence (versus 2D single-shot) is preferable for cord fMRI14 because noise/distortions are mitigated with a reduced echo time. Unfortunately, a stock 3D multi-shot sequence for reliable fMRI is not available across all vendors. Therefore, the three goals of this study were to: (i) develop a 3D multi-shot acquisition protocol for reliable cervical cord fMRI on a Siemens 7T scanner, (ii) further develop an SSSM protocol, and (iii) demonstrate their efficacies in replicating functional connectivity (FC) patterns previously published in the spinal cord.

Methods

All experiments were performed on a Siemens Terra 7T scanner using a custom-built 8-channel pTx/20-channel Rx cervical spine coil15. All participants provided informed consent under protocols approved by the Mass General Brigham Institutional Review Board. We obtained a 3D gradient-echo multi-shot sequence16 through a Siemens C2P agreement with the German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (DZNE) in Bonn, Germany. In early testing, we considered several variants of phase correction (PC) and concluded that PC per blade (PCblade) and PC per volume (PCvol) were viable options for spinal cord fMRI.To achieve our first goal, we acquired resting-state spinal cord fMRI data in healthy subjects (N=13, 10M/3F, age=37.9±9.2y) (one scan with PCblade and one with PCvol) using an acceleration of 2 (=“R2”) (mean scan duration=8:08min): VAT=2.3s, TE=6.75ms, FA=8o, voxels=1x1x4mm3, slices=20, FOV=160mm, phase-encoding direction=AP, C2–C5 coverage, bandwidth: PCvol=1250Hz/Px, PCblade=1302Hz/Px. During these scans, we also developed a shimming strategy using Siemens manual/interactive shimming tools.

To achieve the second goal, we developed an SSSM protocol by increasing the bandwidth (=1358Hz/Px) and acceleration (in-plane=3, through-slice=2) (=“R6”, PCvol): VAT=0.99s, voxels=0.99x0.99x4mm3. Resting state data were acquired in the same cohort (mean scan duration=7:51min). The resultant images exhibited higher thermal noise than their R2 counterparts, as expected, but importantly were not more distorted. After analyzing initial scans, it was apparent that reducing thermal noise was imperative. Thus, we utilized a recently published tool, NORDIC17, and incorporated it into our workflow.

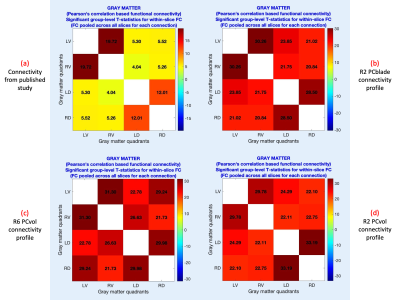

To achieve the third goal, we compared temporal signal-to-noise ratios (tSNR) and within-slice FC. All data were preprocessed in Neptune – custom spinal cord fMRI data processing software that we developed – v1.0 (steps 1, 3–17) with default choices18. Each slice was segmented into four gray-matter quadrants: left(L)/right(R) ventral(V)/dorsal(D) horns, and within-slice FC was computed between all combinations19. For each connection, a one-sample t-test was performed by pooling across all participants and slices (as within-slice FC patterns replicate across slices) (p<0.05, Bonferroni corrected). We hypothesized that our data will replicate the most robust findings in resting state cord fMRI5,9, which is higher LV–RV and LD–RD FC, and relatively lower LV–LD, RV–RD, LV–RD and LD–RV FC.

Results

NORDIC resulted in significant tSNR gains in R6-PCvol (p=0.0002), R2-PCvol (p=0.009) and R2-PCblade (p=0.004) data. TSNR was not significantly different between R2-PCblade and R2-PCvol (p=0.68), but the decisive outcome measure, FC pattern, was slightly more similar to the expected FC pattern in PCblade versus PCvol (Fig.1). R6-PCvol had similar tSNR compared to R2-PCvol after NORDIC (p=0.42) (was lower without NORDIC, p=0.0015). R6-PCvol had similar FC stats (Fig.1), and the FC pattern conformed to prior literature.Discussion and Conclusions

R2-PCblade FC pattern marginally outclassed R2-PCvol for spinal cord fMRI at 7T; hence, we recommend it for studies not requiring SSSM cord fMRI. However, in a small percentage (~10%) of scans (data not shown/used), images acquired using PCblade exhibited unique distortions, which was unexpected and is under investigation. For studies aspiring SSSM fMRI, we recommend R6-PCvol with NORDIC denoising. We were unable to devise an SSSM protocol with R6-PCblade (VAT=1.05s) while maintaining the same number of slices, but based upon our R2 results, we expect its performance to be similar. In conclusion, reliable spinal cord fMRI (with or without sub-second acquisition) is feasible on a Siemens 7T scanner using 3D multi-shot sequences, specific phase corrections, and NORDIC denoising.Acknowledgements

We thank Rüdiger Stirnberg (DZNE, Bonn, Germany) for providing the 3D multi-shot sequence used in this work and for helpful discussions. We also thank Signe Johanna Vannesjo (Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway) and Alan Seifert (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, USA) for helpful discussions. This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) through grants R01EB027779, R21EB031211, and S10OD023637. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.References

[1] B. N. Conrad, R. L. Barry, B. P. Rogers, S. Maki, A. Mishra, S. Thukral, S. Sriram, A. Bhatia, S. Pawate, J. C. Gore and S. A. Smith, "Multiple sclerosis lesions affect intrinsic functional connectivity of the spinal cord.," Brain, vol. 141, no. 6, p. 1650–1664, 2018.

[2] K. T. Martucci, K. A. Weber and S. C. Mackey, "Spinal Cord Resting State Activity in Individuals With Fibromyalgia Who Take Opioids.," Frontiers in neurology, vol. 12, p. 694271, 2021.

[3] J. Cohen-Adad, C. J. Gauthier, J. C. Brooks, M. Slessarev, J. Han, J. A. Fisher, S. Rossignol and R. D. Hoge, "BOLD signal responses to controlled hypercapnia in human spinal cord.," NeuroImage, vol. 50, no. 3, p. 1074–1084, 2010.

[4] R. L. Barry, S. A. Smith, A. N. Dula and J. C. Gore, "Resting state functional connectivity in the human spinal cord," eLife, vol. 3, p. e02812, 2014.

[5] R. L. Barry, B. P. Rogers, B. N. Conrad, S. A. Smith and J. C. Gore, "Reproducibility of resting state spinal cord networks in healthy volunteers at 7 Tesla," NeuroImage, vol. 133, p. 31‐40, 2016.

[6] S. Vahdat, A. Khatibi, O. Lungu, J. Finsterbusch, C. Büchel, J. Cohen-Adad, V. Marchand-Pauvert and J. Doyon, "Resting-state brain and spinal cord networks in humans are functionally integrated.," PLoS biology, vol. 18, no. 7, p. e3000789, 2020.

[7] H. Islam, C. Law, K. A. Weber, S. C. Mackey and G. H. Glover, "Dynamic per slice shimming for simultaneous brain and spinal cord fMRI.," Magnetic resonance in medicine, vol. 81, no. 2, p. 825–838, 2019.

[8] J. Finsterbusch, C. Sprenger and C. Büchel, "Combined T2*-weighted measurements of the human brain and cervical spinal cord with a dynamic shim update.," NeuroImage, vol. 79, p. 153–161, 2013.

[9] F. Eippert, Y. Kong, A. M. Winkler, J. L. Andersson, J. Finsterbusch, C. Büchel, J. Brooks and I. Tracey, "Investigating resting-state functional connectivity in the cervical spinal cord at 3T," NeuroImage, vol. 147, p. 589‐601, 2017.

[10] J. E. Chen, G. H. Glover, N. E. Fultz, B. R. Rosen, J. R. Polimeni and L. D. Lewis, "Investigating mechanisms of fast BOLD responses: The effects of stimulus intensity and of spatial heterogeneity of hemodynamics.," NeuroImage, vol. 245, p. 118658, 2021.

[11] T. Matsui, T. Murakami and K. Ohki, "Neuronal Origin of the Temporal Dynamics of Spontaneous BOLD Activity Correlation.," Cerebral cortex, vol. 1496–1508, no. 29, p. 4, 2019.

[12] K. J. Michon, D. Khammash, M. Simmonite, A. M. Hamlin and T. A. Polk, "Person-specific and precision neuroimaging: Current methods and future directions.," NeuroImage, vol. 263, p. 119589, 2022.

[13] R. L. Barry, S. J. Vannesjo, S. By, J. C. Gore and S. A. Smith, "Spinal cord MRI at 7T.," NeuroImage, vol. 168, pp. 437-451, 2018.

[14] R. L. Barry, B. N. Conrad, S. Maki, J. M. Watchmaker, L. J. McKeithan, B. A. Box, Q. R. Weinberg, S. A. Smith and J. C. Gore, "Multi-shot acquisitions for stimulus-evoked spinal cord BOLD fMRI.," Magnetic resonance in medicine, vol. 85, no. 4, p. 2016–2026, 2021.

[15] N. Lopez Rios, R. Topfer, A. Foias, A. Guittonneau, K. Gilbert, R. Menon, L. Wald, J. Stockmann and J. Cohen-Adad, "Integrated AC/DC coil and dipole Tx array for 7T MRI of the spinal cord," in Proceedings of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, Montréal, QC, Canada, 2019.

[16] R. Stirnberg and T. Stöcker, "Segmented K-space blipped-controlled aliasing in parallel imaging for high spatiotemporal resolution EPI.," Magnetic resonance in medicine, vol. 85, no. 3, p. 1540–1551, 2021.

[17] L. Vizioli, S. Moeller, L. Dowdle, M. Akçakaya, F. De Martino, E. Yacoub and K. Uğurbil, "Lowering the thermal noise barrier in functional brain mapping with magnetic resonance imaging.," Nature communications, vol. 12, no. 1, p. 5181, 2021.

[18] D. Rangaprakash and R. L. Barry, "Neptune: a toolbox for spinal cord functional MRI data processing and quality assurance," in International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine annual meeting, London, UK, 2022.

[19] R. L. Barry, B. N. Conrad, S. A. Smith and J. C. Gore, "A practical protocol for measurements of spinal cord functional connectivity," Scientific Reports, vol. 8, no. 1, p. 16512, 2018.

Figures