0564

Neurodegeneration within upper spinal cord is associated with brain gray matter volume atrophy in early stage of cervical spondylotic myelopathy1Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University, Wuhan, China, 2GE Healthcare, MR Research, Beijing, China

Synopsis

Keywords: Spinal Cord, Neurodegeneration, Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy, Spinal Cord Toolbox

Associations between cross-sectional area and white matter area within the rostral spinal cord and gray matter volume in left supplementary motor area and right middle cingulate gyrus suggest a concordant change pattern and adaptive mechanisms for neuronal plasticity underlying remote neurodegeneration in early cervical spondylotic myelopathy. The atrophy of cross-sectional area within the upper spinal cord and gray matter volume loss in right postcentral gyrus can serve as potential neuroimaging biomarkers of early structural changes within spinal cord and brain preceding marked clinical disabilities in patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy.

INTRODUCTION AND PURPOSE

Cervical spondylotic myelopathy (CSM) is the most common non-traumatic spinal cord injury (SCI) in adults [1]. Since clinical symptoms are not always evident until after years of spinal compression, research on CSM pathology mechanisms harbored the idea that multimodal imaging that exactly characterizes early injury may be crucial for directing appropriate interventions [2]. Besides focal compression, gray matter and with matter also undergo remote neurodegenerative changes beyond the site of cervical stenosis in lumbar cord or even brain [4]. In most of previous studies on patients with CSM, remote neurodegenerative changes such as atrophy and demyelination affecting the entire spinal cord and brain were investigated in isolation [3; 5-6]. To our knowledge, research concentrating on the association between neurodegeneration above the site of compression and brain gray matter volume (GMV) occurring at the early course of CSM is limited. Exploring the relationship between neurodegeneration within the upper spinal cord and brain GMV alternation occurring at the early phase of the disease may help to search for initial clues regarding remote neurodegeneration mechanisms. Furthermore, investigating the remote neurodegenerative changes and their relationship to clinical outcomes may contribute to seek for predictors for assessing early morphologic alternation within the spinal cord and brain prior to marked clinical disabilities.METHODS

Two images were acquired on 3.0 Tesla MR scanner (Discovery MR750, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, Wisconsin): (1) 3D high-resolution axial T2*WI multi-echo recombined gradient-echo sequence (TR / average TE = 30ms / 11.3ms) for assessing spinal cord, gray matter and white matter atrophy; (2) 3D sagittal T1 weighted image using fast spoiled gradient recalled echo sequence (TR / TE = 4ms / Minfull) for the computation of brain GMV. Using Spinal Cord Toolbox software, spinal cord morphometrics (cross-sectional area [CSA], gray matter area [GMA], and white matter area [WMA]) of 40 patients with CSM and 28 healthy controls (HCs) were first computed then compared using two-sample t-test. In addition, the brain cortex GMV of the two groups was analyzed using the voxel-based morphometry (VBM) approach and compared using two-sample t-test. Subsequently, Pearson’s correlation coefficient between spinal cord morphometrics and altered brain cortex GMV was conducted in patients with CSM. Lastly, Spearman’s correlation coefficient between remote neurodegenerative changes and clinical outcomes was implemented in patients with CSM.RESULTS

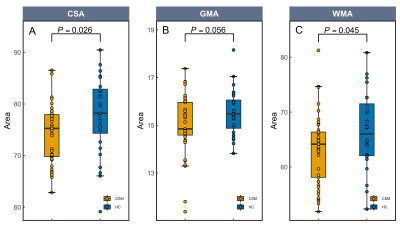

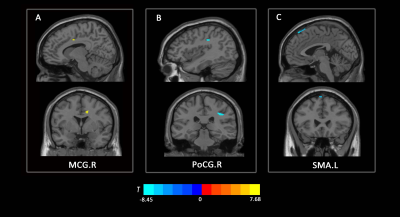

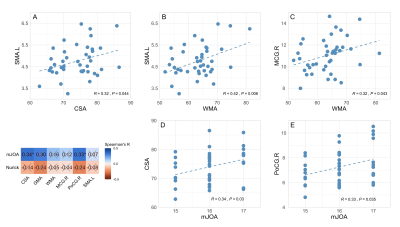

Compared to HCs, CSA and WMA at C2/3 was significantly decreased in patients with CSM (See Fig1A, 1C), and GMA at C2/3 showed a decreasing trend toward significance (See Fig1B). In the VBM analysis, GMV in right middle cingulate gyrus (MCG.R) in patients with CSM was significantly increased compared to HCs (See Fig2A), and decreased in right postcentral gyrus (PoCG.R) and left supplementary motor area (SMA.L) (See Fig2B, 2C). In addition, altered GMV in SMA.L and MCG.R were positively associated with CSA and WMA at C2/3 in patients with CSM (See Fig3A, 3B, 3C). Furthermore, CSA at C2/3 and GMV in the PoCG.R were related to modified Japanese Orthopedic Association (mJOA) scores in patients with CSM (See Fig3D, 3E).DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Slow but continuous cord atrophy above the level of injury is expected in chronic SCI over time and has been frequently documented [4; 7], the significant decreases in CSA and WMA at C2/3 in patients with CSM compared to that in HCs observed in this study is in line with the previous study. GMV atrophy in POCG.R and SMA.L has been suggested to reflect sensorimotor impairment in response to cord compression in patients with CSM [6]. And the increased GMV in MCG.R was suggested due to the innate cortical reorganization and recruitment process to remedy sensory impairment in the early stage phase of CSM. The altered GMV obtained in the present study was in accordance to the prior research [6].We observed GMV loss in SMA.L and CSA and WMA atrophy in upper spinal cord at the early course of CSM. During the course of the disease, the neurodegenerative processes affect efferent motor and afferent sensory pathways and cause sensory and motor deficits [8]. The reduced corticospinal projection from SMA.L to spinal cord was suspected under the procedure of remote neurodegeneration occurring upper spinal cord and SMA.L at the early course of CSM. The association between GMV loss in SMA.L and atrophy of CSA and WMA within rostral spinal cord indicates that remote neurodegeneration in upper spinal cord and brain present a concordant pattern of change. In addition, the correlation between increased GMV in MCG.R and decreased WMA at C2/3 in the present study is in line with the previous findings and may be due to the neuronal plasticity of dendritic sprouting in cortical and spinal cord neurons, which suggests adaptive mechanisms for neuronal plasticity in the rostral spinal cord and brain to restrain clinical impairment in the early phase of spinal compression.

Combined with GMV loss in PoCG.R, CSA atrophy at C2/3 in patients with CSM correlated with mJOA scores is coherent with the previous findings [3] and further corroborates the view that remote neurodegeneration not limit to the site of cord damage could serve as potential neuroimaging biomarkers for evaluating early structural changes within spinal cord and brain prior to the development of obvious clinical disabilities.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all participants for their time and effort. We are deeply grateful to programmer Wei Zhao from ShuKun Technology for her help with installing the Spinal Cord Toolbox software.References

[1] Yarbrough, C. K., Murphy, RK., Ray, W. Z., Stewart, T. J. The Natural History and Clinical Presentation of Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy. Adv Orthop. 2012; 2012:480643.

[2] Matz, P.G., Anderson, P.A., Holly, L.T., Groff, M.W., Heary, R.F., Kaiser, M.G., et al. The natural history of cervical spondylotic myelopathy. J Neurosurg Spine. 2009; 11:104-11.

[3] Grabher, P., Mohammadi, S., Trachsler, A., Friedl, S., David, G., Sutter, R., et al. Voxel-based analysis of grey and white matter degeneration in cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Sci Rep. 2016; 6:24636.

[4] Maryam, S., Wheeler-Kingshott, C., Cohen-Adad, J., Flanders, A.E., Freund, P. Guidelines for the conduct of clinical trials in spinal cord injury: Neuroimaging biomarkers. Spinal Cord. 2019; 57:717-28.

[5] Dong, Y., Holly, L.T., Albistegui-Dubois, R., Yan, X.H., Marehbian, J., Newton, J.M., et al. Compensatory cerebral adaptations before and evolving changes after surgical decompression in cervical spondylotic myelopathy. J Neurosurg Spine. 2008; 9:538-51.

[6] Duggal, N., Rabin, D., Bartha, R., Barry, R.L., Gati, J.S., Kowalczyk, I., et al. Brain reorganization in patients with spinal cord compression evaluated using fMRI. Neurology. 2010; 74:1048-54.

[7] Huber, E., David, G., Thompson, A. J., Weiskopf, N., Mohammadi, S. Dorsal and ventral horn atrophy is associated with clinical outcome after spinal cord injury. Neurology. 2018; 90:E1510-E22.

[8] Hou, J.M., Yan, R.B., Xiang, Z.M., Zhang, H. Brain sensorimotor system atrophy during the early stage of spinal cord injury in humans. Neuroscience. 2014; 266:208-15.

Figures