0562

Spatial distribution of hand-grip motor task activity in spinal cord fMRI

Kimberly J. Hemmerling1, Mark A. Hoggarth1, Milap S. Sandhu2, Todd B. Parrish1, and Molly G. Bright1

1Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, United States, 2Shirley Ryan AbilityLab, Chicago, IL, United States

1Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, United States, 2Shirley Ryan AbilityLab, Chicago, IL, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Spinal Cord, fMRI

A unilateral isometric hand-grip task was used to elicit motor neuron activation in spinal cord fMRI. As predicted, activation was lateralized to the ipsilateral hemicord. However, active voxels were also observed outside of the ventral horn and superior to C7. Reduced spatial precision and sensitivity in activation estimates, particularly along the cord axis, may be due to the combination of inter-individual differences in anatomy, imperfect registration to the standard spinal cord template, additional sensory activity associated with performing the task, and co-contraction of muscles not directly involved in hand-gripping.Introduction

Spinal cord fMRI offers the potential to visualize functional activation patterns in the cord related to sensorimotor activity. Although the technique has historically faced challenges such as low signal to noise ratio, physiological noise, and the small size of the cord1–3, developments in acquisition and analysis techniques have progressed the field. Thus, researchers have used spinal cord fMRI to study motor activation with increasing success4–7. A controlled hand-grip task, which has not yet been widely incorporated into spinal cord fMRI, may be useful in assessing differences in clinical populations8, such as stroke, where hand motor function is impaired. It is imperative, as more studies turn to assess spinal cord function in clinical populations, that the spatial distribution of activation is also accurately characterized in healthy cohorts. In this study, we analyzed spinal cord fMRI during an isometric hand-grip motor task. We hypothesized that cervical spinal cord activation due to a hand-grip task would be localized to the C7-T1 ventral horn of the ipsilateral cord9.Methods

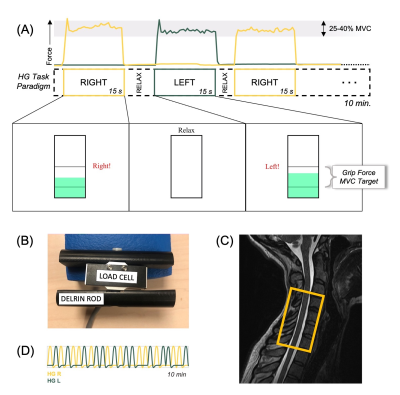

Spinal cord MRI was performed in 28 healthy participants (26.0±4.6y, 18F) using a 3T Siemens Prisma MRI system with a 64-channel head/neck coil and SatPadTM cervical collar. fMRI data were collected in two sessions, before (S1) and after (S2) a 30-minute acute intermittent hypoxia intervention. Participant grip maximum voluntary contraction (MVC) was collected prior to each scan session.During functional scans, participants performed a pseudorandomized isometric hand-grip task with left and right grips (15 each), interspaced by irregular rest periods (Figure 1A). Custom MR-safe hand-grip devices were used (Figure 1B), and real-time visual feedback was displayed to target 25-40% MVC. Spinal cord fMRI was acquired using a GRE EPI sequence with ZoomIT selective excitation (TR/TE=2000/30ms, axial slice thickness=3mm, in-plane resolution=1mm2, 25 slices, FA=90°, FOV=128x44mm2, 300 volumes). The lower edge of the volume was placed just below the C7 vertebra (Figure 1C). Exhaled gases (O2, CO2), pulse, and respiration were collected. A high-resolution anatomical T2-weighted sagittal acquisition was also acquired (TR/TE=1500/135ms, slice thickness=0.8mm, in-plane resolution=0.39mm2, 64 slices, FA=140°, FOV=640mm2).

Physiological data were processed to calculate end-tidal CO2 and RETROICOR regressors10,11. Slicewise motion correction was applied to the raw fMRI data12. The output temporal mean image was manually segmented and used in registration to the standard PAM50 template13,14. Five additional principal component noise regressors were calculated from non-cord signals15. Left and right task regressors were calculated by convolving the block design with the canonical hemodynamic response function (HRF) (Figure 1D).

Data were analyzed using scans from S1 only (N=28) and pooled scans from S1&S2 (N=56) to characterize motor activation. (Note, the impact of the intervention and repeated measures were ignored in this assessment.) First-level fMRI models contained the regressors described above; four statistical contrasts were defined (R>0, L>0, R>L, and L>R). Group-level analyses were performed in the standard PAM50 template space within a group mask. For each contrast, a non-parametric one-sample t-test using threshold-free cluster enhancement (5000 permutations) was used to calculate group-level activation maps with family-wise error rate correction16–18.

Results

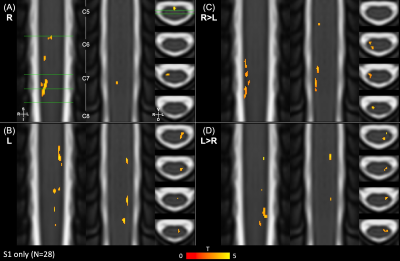

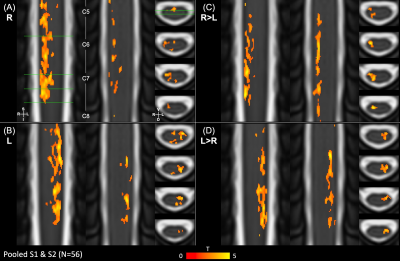

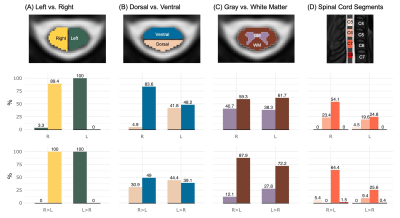

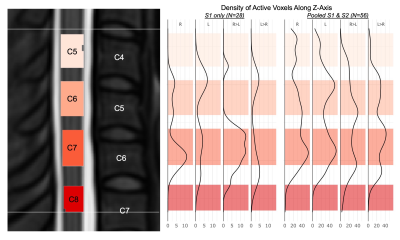

Figures 2 and 3 show S1 only and pooled S1&S2 activation maps, respectively. Activation maps show activity from the right grip primarily in the right hemicord, and from the left grip in the left hemicord. Figure 4 describes the distribution of active voxels (S1 data only) across left and right hemicords, dorsal and ventral hemicords, tissue types, and spinal cord segments. The slicewise count of active voxels in both analyses is shown in Figure 5.Discussion

As expected, spinal cord motor activation due to an isometric hand-grip task is highly lateralized to the ipsilateral hemicord. A high proportion of active voxels lie in the C7 spinal cord segment, relevant but not primarily responsible for hand-gripping motion9. Active voxels appear in both the ventral and dorsal horns, possibly due to sensory feedback associated with the hand-grip task. Many active voxels are also in spinal cord white matter, which may be a result of imperfect registration to standard space, a consequence in part due to poor signal quality19. Additionally, the canonical HRF was used to calculate task regressors, but it has been suggested that the spinal HRF may have different temporal dynamics than the brain20, and therefore may be a source of error in the spatial distribution of motor activity. These results are observed in S1 data and further emphasized when pooling S1&S2. Although it is not appropriate to make statistical inferences on these results (repeated measures are not permitted in this test), this analysis approximates the improved sensitivity from a doubled sample size.Activation was predicted to localize to the C7-T1 spinal cord segments, however we observe active voxels also lie superior to these segments, possibly a consequence of co-contraction of more proximal upper extremity or postural muscles, or due to large inter-individual anatomical variability in the location of spinal cord segments21. Other work mapping motor activation with spinal cord fMRI has also reported activation beyond predicted regions5. Although activation is also expected below the C7 spinal segment, this region is excluded from our data because of insufficient signal quality using our scanner, coil, and scan acquisition approach.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Center for Translational Imaging at Northwestern University. Research supported by the Craig H. Neilsen Foundation (595499). K.J.H. is supported by an NIH funded Training Program (T32EB025766).References

- Eippert, F., Kong, Y., Jenkinson, M., Tracey, I. & Brooks, J. C. W. Denoising spinal cord fMRI data: Approaches to acquisition and analysis. Neuroimage 154, 255–266 (2017).

- Giove, F. et al. Issues about the fMRI of the human spinal cord. Magn Reson Imaging 22, 1505–1516 (2004).

- Kinany, N., Pirondini, E., Micera, S. & van de Ville, D. Spinal Cord fMRI: A New Window into the Central Nervous System. Neuroscientist (2022).

- Yoshizawa, T., Nose, T., Moore, G. J. & Sillerud, L. O. Functional magnetic resonance imaging of motor activation in the human cervical spinal cord. Neuroimage 4, 174–182 (1996).

- Weber, K. A., Chen, Y., Wang, X., Kahnt, T. & Parrish, T. B. Lateralization of cervical spinal cord activity during an isometric upper extremity motor task with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Neuroimage 125, 233–243 (2016).

- Kinany, N. et al. Functional imaging of rostrocaudal spinal activity during upper limb motor tasks. Neuroimage 200, 590–600 (2019).

- Kornelsen, J. & Stroman, P. W. fMRI of the lumbar spinal cord during a lower limb motor task. Magn Reson Med 52, 411–414 (2004).

- Fratini, M. et al. Characterization of the spinal cord fMRI signal in the healthy subjects and in multiple sclerosis patients. Proceedings 30th Scientific Meeting, International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (2022).

- Vanderah, T. W. & Gould, D. J. Spinal Cord. in Nolte’s the Human Brain 233–271 (Elsevier Inc., 2016).

- Glover, G. H., Li, T. Q. & Ress, D. Image-based method for retrospective correction of physiological motion effects in fMRI: RETROICOR. Magn Reson Med 44, 162–167 (2000).

- Brooks, J. C. W. et al. Physiological noise modelling for spinal functional magnetic resonance imaging studies. Neuroimage 39, 680–692 (2008).

- Deshpande, R. & Barry, R. Neptune: a toolbox for spinal cord functional MRI data processing and quality assurance. Proceedings 30th Scientific Meeting, International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (2022).

- de Leener, B. et al. SCT: Spinal Cord Toolbox, an open-source software for processing spinal cord MRI data. Neuroimage 145, 24–43 (2017).

- de Leener, B. et al. PAM50: Unbiased multimodal template of the brainstem and spinal cord aligned with the ICBM152 space. Neuroimage 165, 170–179 (2018).

- Hemmerling, K. J., Hoggarth, M. A., Parrish, T., Barry, R. L. & Bright, M. G. SpinalCompCor: PCA-based denoising for spinal cord fMRI. in Proceedings 30th Scientific Meeting, International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (2022).

- Jenkinson, M., Beckmann, C. F., Behrens, T. E. J., Woolrich, M. W. & Smith, S. M. FSL. Neuroimage 62, 782–90 (2012).

- Nichols, T. E. & Holmes, A. P. Nonparametric Permutation Tests For Functional Neuroimaging: A Primer with Examples. (2001) doi:10.1002/hbm.1058.

- Smith, S. M. & Nichols, T. E. Threshold-free cluster enhancement: Addressing problems of smoothing, threshold dependence and localisation in cluster inference. Neuroimage 44, 83–98 (2009).

- Hoggarth, M. A. et al. Effects of variability in manually contoured spinal cord masks on fMRI co-registration and interpretation. Front Neurol 13, (2022).

- Giulietti, G. et al. Characterization of the functional response in the human spinal cord: Impulse-response function and linearity. Neuroimage 42, 626–634 (2008).

- Cadotte, D. W. et al. Characterizing the location of spinal and vertebral levels in the human cervical spinal cord. American Journal of Neuroradiology 36, 803–810 (2015).

Figures

Figure 1. Experimental design. (A) Schematic of task paradigm, including the hand-grip (HG) force recording, stimulus timing, and visual feedback. “Relax” duration is jittered. (B) MR-safe hand-grip device with load cell and Delrin handle. (C) Placement of fMRI volume overlaid on an anatomical image; the base of the volume box is positioned just below the C7 vertebra and centered on the cord. (D) Example left and right hand-grip task regressors (convolved with canonical HRF).

Figure 2. Spinal cord group-level hand-grip activation maps for S1 scans only. The 4 contrasts for the hand-grip task are shown overlaid on the PAM50 T2 image: (A) R>0, (B) L>0, (C) R>L, and (D) L>R. Group-level statistics were calculated with threshold-free cluster enhancement and are thresholded for significant activation (p<0.05, FWE-corrected). 2 coronal and 4 axial slices are shown for each; the slice locations are indicated (green lines). Approximate spinal cord segments are labeled. FWE=Family-wise error

Figure 3. Spinal cord group-level hand-grip activation maps for pooled S1 & S2 scans (ignoring repeated measures). The 4 contrasts for the hand-grip task are overlaid on the PAM50 T2 image: (A) R>0, (B) L>0, (C) R>L, and (D) L>R. Group-level statistics were calculated with threshold-free cluster enhancement and thresholded for significant activation (p<0.05, FWE-corrected). 2 coronal and 4 axial slices are shown for each; the slice locations are indicated (green lines). Approximate spinal cord segments are labeled. FWE=Family-wise error

Figure 4. Distribution of active voxels across the spinal cord for S1 scans only, showing the percent of active voxels falling within the (A) left vs. right hemicords, (B) dorsal vs. ventral hemicords, (C) gray vs. white matter, and (D) each spinal cord segment C5-C8. The top row represents contrasts 1 (R>0) and 2 (L>0); the bottom row represents contrasts 3 (R>L) and 4 (L>R). Note: Percentages may not add up to 100% because some voxels are not included in the compared regions of interest.

Figure 5. Density of active voxels along the longitudinal axis of the spinal cord. (Left) Probabilistic locations of spinal cord segments C5-C7 within the group mask; vertebrae C4-C7 are labeled. The bounds of the group mask (subject level intersection) are indicated (white lines). (Right) Density of significant activation (voxels per slice) along the superior-inferior spinal cord axis. Shaded regions correspond to the segments on the left panel. Note differences in horizontal axis scaling.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/0562