0560

Diffusion Tensor Imaging and ActiveAx analysis of Post-Mortem Human Cervical Spinal Cord Injury1International Collaboration on Repair Discoveries, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2Physics & Astronomy, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 3Radiology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 4UBC MRI Research Centre, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 5Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 6Vancouver General Hospital, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 7Orthopaedics, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada

Synopsis

Keywords: Spinal Cord, Diffusion/other diffusion imaging techniques, trauma, spinal cord injury, post-mortem, wallerian degeneration, axons, ActiveAx, DTI

7T Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI) and ActiveAx analysis techniques were used to probe the microstructural properties of post-mortem human spinal cord injury tissue. A decrease in DTI fractional anisotropy was observed caudal to (below) the injury epicenter for descending tracts and rostral to (above) the injury epicenter for ascending tracts. All cords displayed increased axon diameter in ascending tracts rostral to the injury site, which may be evidence of axonal swelling. A decrease in axon density for the two subjects with the longest injury-to-death interval may indicate the time scale of Wallerian degeneration-induced axonal damage observable using ActiveAx.

Introduction

Spinal Cord Injury (SCI) clinical outcomes vary greatly based on injury mechanism, severity, and lesion location. Following primary injury, secondary injury occurs over weeks to years due to progressive tissue degeneration1. One such secondary injury mechanism is Wallerian degeneration, which describes the disintegration of axons and myelin sheaths distal to the point of axonal transection or injury2,3. MRI can detect T2 intensity changes associated with Wallerian degeneration as early as 4–7 weeks post-injury4,5. Advanced MRI techniques such as diffusion MRI can probe early changes in tissue morphology that may be attributed to Wallerian degeneration2.Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI) analysis provides metrics of fractional anisotropy (FA), mean diffusivity (MD), radial diffusivity (RD), and axial diffusivity (AD). These metrics can be used to probe information about tissue integrity. However, DTI has limited correlation with specific tissue microstructure properties due to its sensitivity to other factors such as size, density, and orientation distribution of cells, limiting physiological interpretation6,7. Other diffusion MRI analysis approaches have been developed to improve tissue microstructure characterization.

ActiveAx is a diffusion-weighted MRI biophysical modelling technique developed for orientation independent estimations of axon density, axon diameter, and intracellular volume fraction (ICVF)7. ActiveAx benefits from its ability to extract estimations of axon density and diameter along pathways with varying orientations7,8. Although the spinal cord generally consists of fiber tracts of known and constant orientation7, such fibre orientations may be disrupted in damaged spinal cord tissue. Additionally, ActiveAx is designed to account for the distribution of axon diameters within tissue9. Metrics of axon density and diameter, as well as ICVF, allow for information to be gleaned about tissue microstructure in the spinal cord.

Objective: Investigate diffusion MRI metrics of tissue damage following SCI and characterize the effect of injury-to-death interval on these metrics in post-mortem spinal cord tissue.

Methods

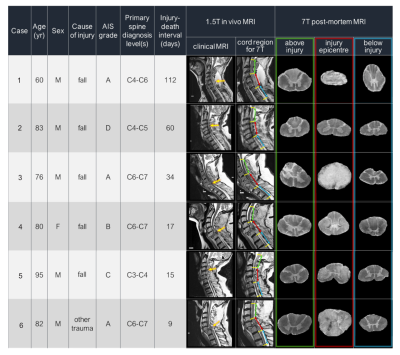

Acquisition: Six full spinal cords were donated to the International SCI Biobank (www.sci-biobank.org) from patients who had suffered acute/sub-acute cervical spinal cord injuries (Figure 1). The injury-to-death interval in patients ranged from 9 to 112 days. The cords were formalin-fixed, and three 4.5cm segments (injury epicenter, above (rostral) epicenter, below (caudal) epicenter) were imaged at 7T (Bruker Biospec, 35mm inner-diameter quadrature volume coil, room temperature). Both anatomical (RARE, resolution=0.1x0.1x1mm3, slices=45) and diffusion imaging (multi-shell 3D diffusion-weighted SE EPI, TR/TE=250/41.21ms, resolution=0.15x0.15x1mm3, six b=0 scans, 5 shells with b=500,1000,2000,3500,5000,7000s/mm2 and 6,15,24,42,60,80 directions respectively, distributed uniformly by a Spherical Code optimization algorithm10) was performed.MRI analysis All data was pre-processed using non-local mean denoising11. Susceptibility and Eddy current corrections were performed on the diffusion images (FSL ‘top up’, ‘eddy’9,12) and fit with DTI and ActiveAx models7(Figure 2a). Manual segmentation was performed on the anatomical images to create white matter (WM) and grey matter masks, which were registered slice-wise to a histological spinal cord atlas using a Coherent Point Drift algorithm13,14 (Figure 2b). DTI and ActiveAx metric values from the ascending, descending, and mixed WM tracts were extracted separately for each slice.

Results

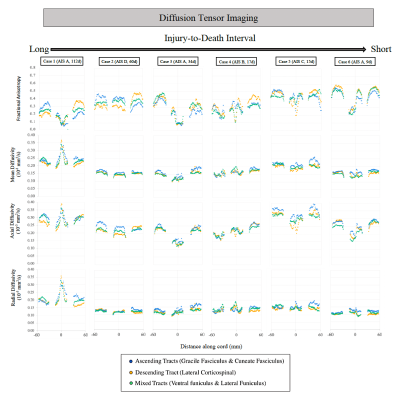

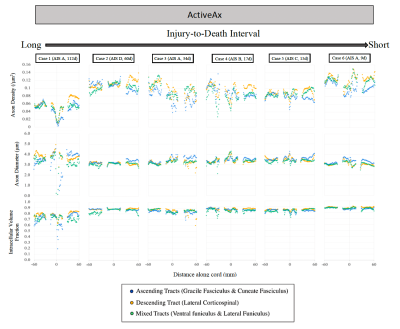

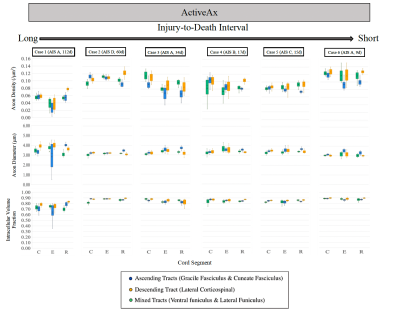

DTI (Figure 3): FA was decreased in ascending tracts rostral to the injury epicenter (average -30.4%) and in descending tracts caudal to the injury epicenter (average -36.3%) in the two cases with the longest injury-to-death interval. A decrease in FA at the injury epicenter was observed for the subjects with the highest injury severity score (AIS=A, Cases 1,3,6, average decrease 71.4%). An increase in MD, RD, and AD was observed across all segments for the subject with the longest injury-to-death interval.ActiveAx (Figure 4 and 5): Axon density, Axon diameter and ICVF were lowest for the subject with the longest injury-to-death interval. Axon density in descending tracts was decreased caudal to the injury epicentre for the two cases with the longest injury-to-death interval (average decrease 19.8%). Axon diameter in ascending tracts was increased rostral to the injury epicentre for all cases (average +10.6%). A large disruption in ActiveAx metrics was observed at the injury site for all subjects, with metric abnormality increasing with increasing AIS score.

Discussion

ActiveAx and DTI were used to investigate tissue microstructure of traumatically injured human spinal cords. Decreased FA rostral to the injury epicentre in ascending tracts and caudal to the injury epicenter in descending tracts could be attributed to the effects of Wallerian degeneration on WM integrity, as seen in previous in vivo SCI studies15. Increased axon diameter rostral to the injury epicentre in ascending tracts could be due to axonal swelling possibly linked to Wallerian degeneration. Decreased axon density in the two cases with the longest injury-to-death interval could be attributed to Wallerian degeneration-induced tract atrophy. This observation of decreased axon density in patients with injury-to-death intervals greater than 60 days may indicate the utility of ActiveAx in determining the time scale of axonal degeneration with the benefit over DTI of orientation independent calculations and increased correlation with tissue microstructure metrics.Conclusion

Increased axon diameter rostral to the injury epicentre in ascending tracts was observed for all SCI subjects, which may indicate ActiveAx’s ability to detect axonal swelling. Decreased axon density observed only in patients with long (>60 day) injury-to-death intervals may indicate the time scale for the detection of axonal degeneration using ActiveAx metrics.Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the patients and families for donating their tissue to the International Spinal Cord Injury Biobank. Funding for this study and the Biobank was obtained from the Craig H. Neilsen Foundation, NSERC, Blusson Integrated Cures Partnership (BICP), VGH and UBC Hospital Foundation and the Rick Hansen Foundation, and an International Collaboration on Repair Discoveries (ICORD) seed grant. This work was conducted on the traditional, ancestral, and unceded territories of Coast Salish Peoples, including the territories of the xwməθkwəy̓əm (Musqueam), Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish), Stó:lō and Səl̓ílwətaʔ/Selilwitulh (Tsleil- Waututh) Nations.

References

[1] Alizadeh A., Dyck S. M. and Karimi-Abdolrezaee S., "Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury: An Overview of Pathophysiology, Models and Acute Injury Mechanisms," Frontiers in Neurology, vol. 19, 2019. |

[2] Fischer T., Stern C., Freund P., Schubert M. and Sutter R., "Wallerian degeneration in cervical spinal cord tracts is commonly seen in routine T2-weighted MRI after traumatic spinal cord injury and is associated with impairment in a retrospective study," European Radiology, vol. 31, no. 5, pp. 2923-2932, 2021. |

[3] Gaudet A. D., Popovich P. G. and Ramer M. S., "Wallerian degeneration: Gaining perspective on inflammatory events after peripheral nerve injury," Journal of Neuroinflammation, vol. 8, p. 110, 2011. |

[4] Becerra J. L., Puckett W. R., Hiester E. D., Quencer R. M., Marcillo A. E., Post M. J. and Bunge R. P., " MR-pathologic comparisons of wallerian degeneration in spinal cord injury," American Journal of neuroradiology, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 125-133, 1995. |

[5] Kuhn M. J., Mikulis D. J., Ayoub D. M., Kosofsky B. E., Davis K. R. and Taveras J. M., "Wallerian degeneration after cerebral infarction: evaluation with sequential MR imaging," Radiology, vol. 172, p. 179, 1989. |

[6] Duval T., McNab J. A., Setsompop K., Witzel T., Schneider T., Huang S. Y., Keil B., Klawiter E. C., Wald L. L. and Cohen-Adad J., "In vivo mapping of human spinal cord microstructure at 300 mT/m," Neuroimage, vol. 118, pp. 494-507, 2016. |

[7] Alexander D. C., Hubbard P. L., Hall M. G., Moore E. A., Ptito M., Parker G. J. M. and Dyrby T. B., "Orientationally invariant indices of axon diameter and density from diffusion MRI," NeuroImage, pp. 1374-1389, 2010. |

[8] Sepehrband F., Alexander D. C., Kurniawan D. N., Reutens D. C. and Yang Z., "Towards higher sensitivity and stability of axon diameter estimation with diffusionweighted MRI," NRM in biomedicine, vol. 26, pp. 293-308, 2015. |

[9] Andersson J. L. R. and Sotiropoulos S. N., "An integrated approach to correction for off-resonance effects and subject movement in diffusion MR imaging," NeuroImage, vol. 125, pp. 1063-1078, 2016. |

[10] Cheng J., Shen D., Yao P. T. and Basser P. J., "Single- and Multiple-Shell Uniform Sampling Schemes for Diffusion MRI Using Spherical Codes," IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, vol. 37, pp. 185-199, 2018. |

[11] Coup P. and et. al., "An optomized blockwise nonlocal means denoising filter for 3-D magnetic resonance images," IEEE Transaction on Medical Imaging, vol. 27, pp. 425-441, 2008. |

[12] Andersson J. L. R., Skare S. and Ashburner J., "How to correct susceptibility distortions in spin-echo echo-planar images: application to diffusion tensor imaging," NeuroImage, vol. 20, pp. 870-888, 2003. |

[13] Myronenko A. and Song X., "Point-Set Registration: Coherent Point Drift," IEEE Transaction on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, vol. 32, pp. 2262-2275, 2010. |

[14] Sengul G., Watson C., Tanaka I. and Paxinos G., "Atlas of the spinal cord: Mouse, rat, rhesus, marmoset and human," Elsevier, 2012. |

[15] Cohen-Adad J. and et. al., "Demyelination and degeneration in the injured human spinal cord detected with diffusion and magnetization transfer MRI," NeuroImage, vol. 55, pp. 1024-1033, 2011. |

Figures

Figure 1: Patient donor information from the International Spinal Cord Injury Biobank. In vivo clinical images were obtained at 1.5T prior to death with rostral, epicenter and caudal spinal cord segments denoted in green, red, and blue, respectively. Anatomical axial images at 7T are given for each segment. (AIS grades: A= Complete loss of motor/sensory function below injury, B= sensory but no motor function below injury, C= motor function below injury with < 1⁄2 muscle function, D= motor function below injury with > 1⁄2 muscle function)

Figure 2: (a) representative DTI and ActiveAx metric maps for Case 5 rostral segment slice (b) Spinal cord segmentation atlas for representative slice: Ascending Tracts, Descending Tract, and Mixed Tracts are denoted in blue, yellow, and green, respectively. Injury schematic not to scale.

Figure 3: Diffusion tensor imaging metrics for each patient are shown for a ~12 cm portion of spinal cord with injury epicenter located at 0mm (+60 mm = rostral end of cord portion, -60 mm = caudal end of cord portion). AIS severity score and injury-to-death interval for each case are indicated in brackets.

Figure 4: ActiveAx imaging metrics for each patient are shown for a ~12 cm portion of spinal cord with Injury epicenter located at 0mm (+60 mm = rostral end of cord portion, -60mm = caudal end of cord portion). AIS severity score and injury-to-death interval for each case are indicated in brackets.

Figure 5: ActiveAx average metrics for the Rostral, Epicenter, and Caudal (R, E, and C, respectively) 4.5 cm cord segments. AIS severity score and injury-to-death interval for each case are indicated in brackets.