0559

Alterations in intrinsic functional networks in squirrel monkey spinal cord after focal damage to primary motor cortex using resting state fMRI1Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Spinal Cord, fMRI (resting state), Functional Connectivity

The goal of this study was to detect and quantify how functional connectivity within networks in squirrel monkey spinal cord changes after a focal lesion of the primary motor cortex. We first used independent component analysis to identify 7 spatially independent functional hubs within each segment of the cervical spinal cord. The overall connectivity of these spinal cord networks increased after a lesion within M1, indicating plastic changes in spinal cord due to cortical injury. Distinct functional communities confined to neighboring spinal cord segments were identifiable one week after the injury, confirming spinal cord functional networks reorganized over that time.

Introduction

The spinal cord is responsible for the transmission and integration of signals to and from the brain, and acts as the primary interface between the central and peripheral nervous systems1. An injury to the brain may result in motor and/or sensory dysfunction2,3 and affect its communication with the spinal cord. Plastic changes, including reactivation and reorganization of brain functional networks, are believed to play crucial roles in the recovery after a brain injury4–6. Previous MRI studies have documented brain reorganization after a spinal cord injury, but few studies have reported the reverse situation7,8. Here, we aimed to first identify and delineate resting state functional networks in normal squirrel monkey spinal cord without prior hypotheses of their location. To achieve this, we use Independent Component Analysis (ICA) of resting state BOLD fMRI signals in a data-driven, hypothesis-free approach. Further, it is known that corticospinal axons from primary motor cortex (M1) are connected with the motor neurons and interneurons in the ventral spinal cord to affect motor control9,10. We therefore designed a study to quantify the longitudinal plastic changes in spinal cord functional circuits subsequent to a disruption of descending motor control input to the cervical spinal cord ventral horns by a targeted lesion of the hand region in M1 cortex of the squirrel monkey brain.Methods

Images of five axial slices, covering C3-C7 cervical segments, were acquired using a custom neck coil and an Agilent 9.4T scanner in anaesthetized squirrel monkeys. Resting state fMRI data (300 dynamics) were acquired using a fast gradient echo sequence (flip angle = ~18°, TR = 46.88ms, TE: 6.5ms, 3s per volume). Data were acquired from 15 normal monkeys and one M1 lesioned monkey before injury and at weeks 1 and 6 post-injury. Motion and physiological signal corrections (RETROICOR) and band pass filtering (0.01-0.1 Hz) were performed on the fMRI data, followed by co-registration to a customized template using FSL in order to facilitate group level analyses11,12. Next, group spatial ICA was performed by temporal concatenation of all the data using GIFT software, and thirty-five spatially independent components were extracted from within the butterfly-shaped gray-matter region of spinal-cord13,14. These components were identified to belong to different functional hubs by visually comparing them with the anatomy of spinal cord. Next, functional connectivities between these hubs were computed for one M1-lesioned monkey both before and after injury, by correlating (Pearson’s correlation) their fMRI time courses, and significant changes were noted across time. Community structures were obtained based on connectivity measures and graph theory15,16, which depict the functional network organization within and across spinal segments before and after injury. Finally, the connectivity matrix was rearranged such that the connectivities within each community are next to each other in order to illustrate the community behavior.To create the lesion, standard intracranial microstimulation procedures were first used to determine which regions evoked muscle movements of the hand and arm. Next, ibotenic acid, which causes toxicity and neuronal death, was used to lesion the pre-determined hand region6.

Results

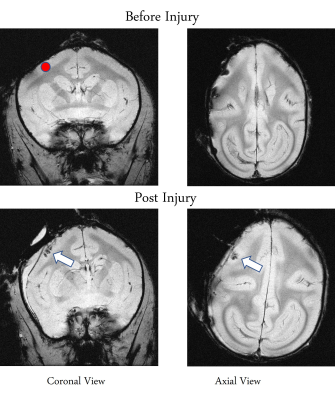

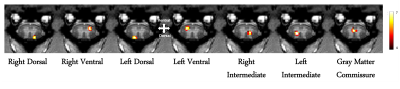

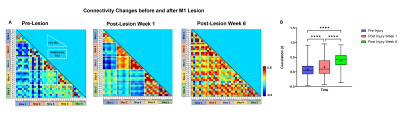

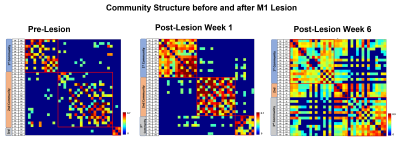

The M1 lesion is evident as a hypointense region in the post lesion structural T2*W images of the squirrel monkey brain as shown in Figure 1. In the spinal cord, ICA decomposed resting state fMRI data of 15 normal monkeys into seven spatially distinct ROIs/functional hubs in each segment: left/right dorsal horns, left/right ventral horns, left/right intermediate region which extended from the dorsal to the middle part of spinal cord, and gray-commissure region (GC), which is the thin strip of gray matter located at the central junction between the two hemi-cords, as shown for a representative slice in Figure 2. Connectivity measures between these 7 functional hubs from the 5 segments (C3-C7), revealed that there were significant increases post-lesion at 1-week and further at 6-weeks as shown in Figure 3. Before injury, the community structure obtained using the connectivity values was spread within and across multiple slices/segments as shown in Figure 4. However, after M1 lesion at week 1, connectivity increased between functional hubs of Slice 2 and 3, Slice 4 and 5, and Slice 1 separately, forming 3 communities. At week 6, the three major communities consisted of ventral and GC region of Slice 2,3,4,5 and Slice 1 separately, and the dorsal and intermediate hubs from all the slices.Discussion and Conclusion

The location of the seven functional hubs in the spinal cord obtained using ICA from normal monkeys corroborate well with our previous published results17. The increase in overall functional connectivity at Week 1 and Week 6 suggests a compensatory mechanism occurs after M1 lesion deprives the spinal cord of descending motor controlling inputs. The reorganization of spinal cord networks into strong communities confined to neighboring segments was also visually evident from their connectivity matrix structure at Week 1 post-lesion. Similar community structure formation has also been observed previously, in studies showing spinal cord injury effects17. Also, the formation of separate communities from the dorsal hubs and from the ventral and GC hubs have been reported in our previous study17. Once we have sufficient sample size, the results from this study will provide valuable information about how targeted M1 lesion affects specific functional hubs of spinal cord.Acknowledgements

Funding Source:

R01 NS078680 and R01NS092961

The authors acknowledge Chaohui Tang

for animal preparation.

References

1. Prochazka A, Mushahwar VK. Spinal cord function and rehabilitation - An overview. J Physiol 2001;533:3–4.

2. Nudo RJ. Recovery after brain injury: Mechanisms and principles. Front Hum Neurosci 2013;7:1–14.

3. Warren G. Darling*, Marc A. Pizzimenti† and RJM. Lesions in Non-Human Primates : Experimental IMPLICATIONS FOR HUMAN STROKE PATIENTS. J Integr Neurosci 2011;10:353–84.

4. Higo N. Non-human Primate Models to Explore the Adaptive Mechanisms After Stroke. Front Syst Neurosci 2021;15:1–8.

5. Sato T, Nakamura Y, Takeda A, et al. Lesion Area in the Cerebral Cortex Determines the Patterns of Axon Rewiring of Motor and Sensory Corticospinal Tracts After Stroke. Front Neurosci 2021;15:1–14.

6. Murata Y, Higo N, Oishi T, et al. Effects of motor training on the recovery of manual dexterity after primary motor cortex lesion in macaque monkeys. J Neurophysiol 2008;99:773–86.

7. Wang L, Zheng W, Yang B, et al. Altered functional connectivity between primary motor cortex subregions and the whole brain in patients with incomplete cervical spinal cord injury. Front Neurosci 2022:1–11.

8. Freund P, Weiskopf N, Ashburner J, et al. MRI investigation of the sensorimotor cortex and the corticospinal tract after acute spinal cord injury: A prospective longitudinal study. Lancet Neurol 2013;12:873–81.

9. Ueno M, Nakamura Y, Li J, Gu Z, Niehaus J, Maezawa M, Crone SA, Goulding M, Baccei ML YY. Corticospinal Circuits from the Sensory and Motor Cortices Differentially Regulate Skilled Movements through Distinct Spinal Interneurons. Cell Rep 2018;23:1286–1300.

10. Zaaimi B, Edgley SA, Soteropoulos DS, et al. Changes in descending motor pathway connectivity after corticospinal tract lesion in macaque monkey. Brain 2012;135:2277–89.

11. Jenkinson M, Smith S. A global optimisation method for robust affine registration of brain images. Med Image Anal 2001;5:143–56.

12. Glover GH, Li TQ, Ress D. Image-based method for retrospective correction of physiological motion effects in fMRI: RETROICOR. Magn Reson Med 2000;44:162–7.

13. Beckmann C, Mackay C, Filippini N, et al. Group comparison of resting-state FMRI data using multi-subject ICA and dual regression. Neuroimage 2009;47:S148.

14. Calhoun VD, Adali T, Pearlson GD, et al. Group ICA of Functional MRI Data: Separability, Stationarity, and Inference. Proc ICA 2001 2001. [Epub ahead of print].

15. Newman MEJ. Finding community structure in networks using the eigenvectors of matrices. Phys Rev E - Stat Nonlinear, Soft Matter Phys 2006;74:1–19.

16. Rubinov M, Sporns O. Complex network measures of brain connectivity: Uses and interpretations. Neuroimage 2010;52:1059–69.

17. Sengupta A, Mishra A, Wang F, et al. NeuroImage Functional networks in non-human primate spinal cord and the effects of injury. Neuroimage 2021;240:118391.

Figures