0546

Feasibility of accelerated non-contrast-enhanced whole-heart bSSFP coronary MRA by deep learning constrained compressed sensing

Xi Wu1,2, Jiayu Sun1, and Xiaoyong Zhang3

1West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China, 2Affiliated Hospital of North Sichuan Medical College, Nanchong, China, 3Clinical Science, Philips Healthcare, Chengdu, China

1West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China, 2Affiliated Hospital of North Sichuan Medical College, Nanchong, China, 3Clinical Science, Philips Healthcare, Chengdu, China

Synopsis

Keywords: Vessels, Cardiovascular, deep learning

The balanced steady-state free precession (bSSFP) sequence is widely used for navigated whole-heart coronary magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) for the evaluation of coronary anatomy and abnormalities due to its inherently high blood signal intensity and blood-myocardial contrast. However, the main drawback of this approach is that the scan time is longer and prone to interference with motion artifacts. In this study, we investigated the utility of whole-heart coronary MRA using accelerated bSSFP with compressed sensing artificial intelligence (CSAI) technique at 3 Tesla. The results demonstrated the adopted CS-AI technique yielded high image quality within a clinically feasible acquisition time in healthy subjects and patients with suspected CAD.Introduction

Currently, the balanced steady-state free precession (bSSFP) sequence is widely used for navigated whole-heart coronary magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) for the evaluation of coronary anatomy and abnormalities due to its inherently high blood signal intensity and blood-myocardial contrast1-3. However, the limitation of long acquisition time still exists in whole-heart bSSFP coronary MR angiography4, 5, which may increase the odds of patient motion and induce heart rate and respiratory pattern drift, thereby degrading the final image quality. Compressed sensing (CS) could be used to achieve scan time reduction beyond that possible with conventional parallel imaging acceleration. But they generally have the challenge of choosing optimal sparsity transforms and tuning parameters.Recently, there is a high capacity for improving compressed sensing algorithms in which multi-scale sparsification from sparsity transform is replaced by deep learning implementation, which shows superior performance in knee6 and ankle7 MR reconstructions. Based on the characteristics of the “learned implementation” strategy, denoising can be improved through efficient optimization of the denoising level and good edge preservation. Thus, the present study aimed to perform a validation analysis to evaluate the feasibility of the compressed sensing artificial intelligence (CSAI) technique in non-contrast, free-breathing, whole-heart 3T coronary MRA on healthy subjects and individuals with suspected coronary artery disease (CAD).

Methods

This study was approved by the institutional ethics committee. All 42 participants were scanned on a 3T clinical MR scanner (Ingenia Elition, Philips Healthcare Best) with a 16-channel body matrix coil combined with a 12-channel spine matrix coil. Non-contrast whole-heart coronary MRA was acquired under free-breathing in three-dimensional coronal imaging planes by using a bSSFP sequence with a 3D non-selective pulse. The details of coronary MRA parameters were listed as follows: TR/TE = 2.4/1.2 ms; flip angle= 10°; field of view= 280×280×240 mm3; Acquisition voxel size= 1.5×1.5×1.5mm3; Reconstruction voxel size= 0.75×0.75×0.75mm3. For healthy subjects, whole-heart coronary MR angiography was acquired by employing (a) a SENSE factor of 4 (2×2, in the anteroposterior and superior-to-inferior directions), (b) a CS acceleration factor of 5, and (c) CSAI with an acceleration factor of 5. The order of the three acquisitions was randomized for each participant. In patients with suspected CAD, coronary MR angiography was acquired with a CSAI acceleration factor of 5.For healthy subjects, subjective image quality was independently scored by four cardiac MR radiologists using a 5-point scale (1= nonassessable status, 5=excellent visualization) on the assessment of segment with a diameter over 1.5 mm on original images. Images with a score ≥3 were considered to be satisfactory and acceptable for diagnosis. If there were disagreement between the observers, the final result was obtained by discussion. For quantitative objective assessment, blood pool homogeneity, signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) were calculated for comparison between the three techniques. The image scores and quantitative parameters were compared using the Wilcoxon signed rank test. Bland-Altman plots were used to perform a visual comparison of differences between paired measures against their averages. A P value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results and Discussion

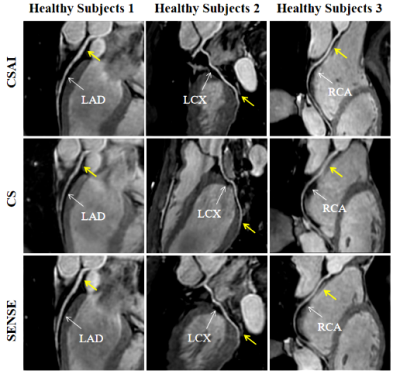

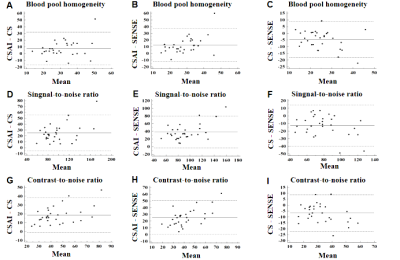

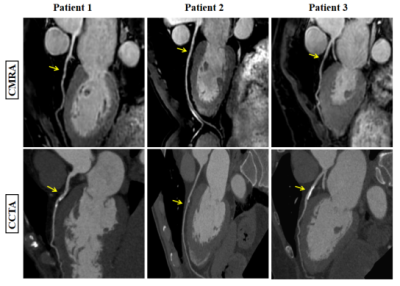

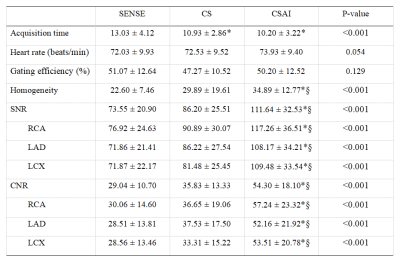

As shown in Table 1, acquisition time was significantly shorter in the CSAI and CS groups than in the SENSE group (10.2 ± 3.2 min vs. 10.9 ± 2.9 min vs. 13.0 ± 4.1 min, p<0.001). However, the CSAI approach had highest image quality scores (4.23 ± 0.90 vs. 3.53 ± 0.94 vs. 3.53 ± 0.86), blood pool homogeneity (34.89 ± 12.77 vs. 29.89 ± 19.61 vs. 22.60 ± 7.46), mean SNR value (111.64 ± 32.53 vs. 86.20 ± 25.51 vs. 73.55 ± 20.90), and mean CNR value (54.30 ± 18.10 vs. 35.83 ± 13.33 vs. 29.04 ± 10.70) (all p<0.001) compared with the CS and SENSE approaches. Coronary MRA images for three representative healthy participants are shown in Figure 1, where CSAI had best lumen visualization with minimal image noise and clear vessel edges than SENSE and CS methods. The Bland-Altman plots revealed acceptable agreement for the CSAI/SENSE, CS/SENSE, and CSAI/CS pairs with respect to corresponding blood pool homogeneity, SNR, and CNR (Figure 2). In the patient study, CSAI coronary MRA demonstrated good agreement and superior local lumen visualization compared with CCTA, and the typical example images were shown in Figure 3.Conclusion

This study employed a compressed sensing artificial intelligence framework to enable non-contrast free-breathing whole-heart bSSFP coronary MRA, which yielded high image quality within a clinically feasible acquisition time in healthy subjects and patients with suspected CAD. Ultimately, this non-invasive and radiation free approach could be a promising tool for rapid screening and comprehensive examination of the coronary vasculature in patients with suspected CAD.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement foundReferences

1. Finn JP, Nael K, Deshpande V, et al. Cardiac MR imaging: state of the technology[J]. Radiology, 2006,241(2):338.2. Androulakis E, Mohiaddin R, Bratis K. Magnetic resonance coronary angiography in the era of multimodality imaging[J]. Clinical Radiology, 2022.

3. Hajhosseiny R, Rashid I, Bustin A, et al. Clinical comparison of sub-mm high-resolution non-contrast coronary CMR angiography against coronary CT angiography in patients with low-intermediate risk of coronary artery disease: a single center trial[J]. Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, 2021,23(1).

4. Kato Y, Ambale-Venkatesh B, Kassai Y, et al. Non-contrast coronary magnetic resonance angiography: current frontiers and future horizons[J]. Magnetic Resonance Materials in Physics, Biology and Medicine, 2020,33(5):591-612.

5. Hajhosseiny R, Munoz C, Cruz G, et al. Coronary Magnetic Resonance Angiography in Chronic Coronary Syndromes[J]. Frontiers in cardiovascular medicine, 2021,8:682924.

6. Pezzotti N, Yousefi S, Elmahdy M S, et al. An Adaptive Intelligence Algorithm for Undersampled Knee MRI Reconstruction[J]. IEEE Access, 2020,8:204825-204838.

7. Foreman S C, Neumann J, Han J, et al. Deep learning–based acceleration of Compressed Sense MR imaging of the ankle[J]. European Radiology, 2022.

Figures

Figure 1 Coronary MR angiography images reformatted along the left anterior descending (LAD), left circumflex (LCX), and right coronary artery (RCA) for three representative healthy participants. 3D bSSFP coronary MR angiography images were obtained with the proposed compressed sensing artificial intelligence (CSAI, top row), compressed sensing (CS, middle row), and sensitivity encoding (SENSE, bottom row).

Figure 2. Bland-Altman plots for blood pool homogeneity, signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) for CSAI/CS (A, D, G), CSAI/SENSE (B, E, H), and CS/SENSE (C, F, I). The y-axis reflects differences between the paired measures. The x-axis represents the means of the paired measures. The solid and dotted lines are mean differences and 95% limits of agreement, respectively. CS, compressed sensing; CSAI, compressed sensing artificial intelligence; SENSE, sensitivity encoding.

Figure 3 Reformatted non-contrast whole-heart CMRA (top row) and CCTA (below row) images along the LAD for three patients (patients 1, 2, and 3). Coronary MR angiography images disclose stenosis (yellow arrow) in the LAD matching the lesion detected by CCTA. Abbreviations: CMRA, coronary magnetic resonance angiography; CCTA, coronary computed tomography angiography.

Table 1 Scan-relevant parameters and objective image quality comparison among the three groups. CNR, contrast-to-noise ratio; LAD, left anterior descending artery; LCX, left circumflex; RCA, right coronary artery. * versus SENSE, p<0.001; § versus CS, p<0.001.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/0546