0535

MR-double-zero in vivo: Model-free and live MRI contrast optimization running a loop over a real scanner with a real subject.1High-field Magnetic Resonance Center, Max Planck Institute for Biological Cybernetics, Tuebingen, Germany, 2Department for Biomedical Magnetic Resonance, University Hospital Tuebingen, Tuebingen, Germany, 3Institute of Neuroradiology, University Hospital Erlangen, Friedrich-Alexander University Erlangen-Nürnberg, Erlangen, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: Pulse Sequence Design, Pulse Sequence Design

Recently, we proposed a framework for automatized, model-free MR sequence design for contrast generation. The concept was proven by optimizing the contrast-generating sequence using a real MRI scanner for scanning model solutions repeatedly until convergence to the target. In this work, we demonstrate for the first time that this live optimization loop can also be used directly on a real subject’s brain. As an example, GM/WM contrast for a GRE sequence was optimized fully automatically in a model-free and reference-free manner live in a healthy subject at a 3T MR scanner.Introduction

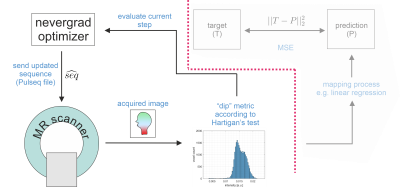

We recently proposed a framework for automatized, model-free MR sequence design and for parameter optimization termed MR-double-zero1. For that, a closed live optimization loop consisting of (i) updating a parametrized sequence, (ii) executing it at the real scanner, and (iii) evaluating a loss function based on the current iteration’s reconstruction was established. Whilst the first proof of concept was performed in model solutions, herein we demonstrate a first live and model free optimization in vivo.In this this work the live optimization of FA, TR and TE of a gradient echo sequence is performed with the goal to maximize a histogram-based tissue contrast metric, i.e. Hartigan’s dip test2, a measure for non-unimodality of the image intensity histograms. Without signal model or tissue parameters, maximizing this metric, which can be directly evaluated on the individual images at each iteration, allows increasing the MR image contrast live, in a human brain. Additionally, the metric does not rely on an accurate segmentation of GM/WM tissue, which is hard to obtain in a real-time optimization and also would need to be updated in case of subject motion.

Methods

The basic idea is to optimize an MR sequence for GM/WM contrast by automatically adapting TE, TR and FA during an in vivo examination using MR-double-zero. The experimental setup as presented in1 is slightly adapted: loss is now determined with Hartigan’s dip test (implemented by3 available via4). This metric will enforce tissue contrast which would ideally manifest as a bimodal/multimodal distribution. The optimization objective can be formulated as$$\text{FA}^*,\text{TR}^*,\text{TE}^* = \underset{\text{FA,TR,TE}}{\arg\min} \left\{ -\text{Hdip}\left(\text{scan}(\text{seq}(\text{FA,TR,TE}))\right) \right\}$$

where seq(FA,TR,TE) is the parametrized Pulseq5 sequence, scan() represents acquisition and reconstruction at the real scanner system, and Hdip() is the chosen metric (larger means less unimodal).

Details on the proposed framework are depicted in Figure 1. MRI examinations were performed at a 3T MR scanner (Siemens, Germany) in agreement with the local ethics committee. The fully sampled RF and gradient-spoiled 2D GRE sequence is implemented in Pulseq. This allows modifying TE, TR and FA either manually, or with an optimizer by generating a new *.seq file and sending it to the scanner where it gets executed automatically using a modified Pulseq interpreter6. In case of automatic optimization, impossible combinations of TE/TR were avoided by application of constraints to the optimizer. The optimization process was controlled remotely and not from the scanner’s host computer, which provides more freedom regarding the use of different types of software. Raw data was reconstructed by an FFT, and magnitude images were masked manually (coarse skull stripping) once before the first iteration to avoid influence of background noise to the loss. As in prior work, the CMA-ES optimization algorithm8 implemented in nevergrad9 was chosen for this non-differentiable, non-convex and noisy optimization problem. One iteration took 20 to 70 seconds, the whole optimization approx. 90 minutes.

Results

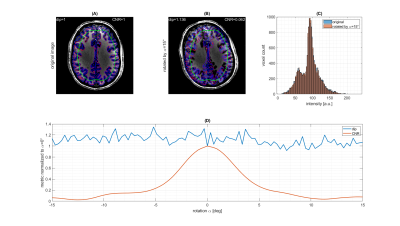

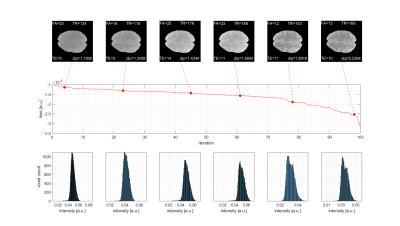

The results of the model free and live optimization pipeline are shown in Figure 2. As the algorithm explores the parameter space randomly, the images were sorted by loss retrospectively. The used -Hdip metric clearly correlates with the increase in contrast and live optimization shows intermediate results with quite different parameter combinations and image contrast (Figure 2a). Once the loss decayed below approximately -1.5·10-3 a clear grey-white matter contrast is enforced and further increased. The decrease of the loss curve in Figure 2b indicates that a lower minimum might even be possible. Yet the discovery was possibly limited by the finite number of iterations of 100, but the optimization could potentially be continued in another session.The histogram-based loss metric has two major benefits: (i) as no target image is used, the optimization is not driven towards a certain predefined contrast, but can freely discover solely governed by the increase of contrast. (ii) With a loss based on a target image (e.g. CNR), motion between the current iteration and the target would be problematic, while the histogram-based loss is found to be stable against simulated motion (Figure 3).

Discussion

It was demonstrated that without major modifications it is possible to perform the model free and live optimization MR-double-zero as well in vivo. As a first example, contrast between GM and WM was optimized, by adapting TE, TR and FA. Still, no signal equation had to be provided (= model-free) but the optimization was fully data driven, again, in line with the initial idea behind the MR-double-zero project. Future projects might require the implementation of prospective motion correction, especially for subjects that may not be able to avoid motion over the course of the optimization, which is longer than typical clinical applications of MRI. Also, further investigations e.g. on the effect of optimizer settings such as step-size or start values, or the masking need to be performed. Nevertheless, judging from the presented findings, it seems to be reasonable to assume that besides parameter optimization also full sequence design should be possible in vivo with MR-double-zero.Conclusion

MR-double-zero can be applied for model-free and live optimization as well in vivo, and yields first, promising results. The model- and reference-free approach promises novel paths for the exploration of MRI strategies directly in the organ of interest.Acknowledgements

The financial support of Max Planck Society, German Research Foundation (Reinhart Koselleck project DFG SCHE658/12 and ZA 814/7-1) and ERC Advanced Grant, No 834940 is gratefully acknowledged.References

1 F. Glang, S. Mueller, K. Herz et al., MR-double-zero – Proof-of-concept for a framework to autonomously discover MRI contrasts, JMR 341 (2022) 107237, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmr.2022.107237

2 J. A. Hartigan. P. M. Hartigan., The Dip Test of Unimodality., Ann. Statist. 13 (1) 70 - 84, March, 1985. https://doi.org/10.1214/aos/1176346577

3 F. Mechler, D. L. Ringach, On the classification of simple and complex cells, Vision Research, Vol. 42, Issue 8, 2002, 1017-1033, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0042-6989(02)00025-1

4 D. Schluppeck, https://gist.github.com/schluppeck/e7635dcf0e80ca54efb0, GitHub

5 Layton, K.J., Kroboth, S., Jia, et al., Pulseq: A rapid and hardware-independent pulse sequence prototyping framework. Magn. Reson. Med., 77: 1544-1552. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.26235

6 Loktyushin, A, Herz, K, Dang, N. et al., MRzero - Automated discovery of MRI sequences using supervised learning. Magn Reson Med. 2021; 86: 709– 724. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.28727

7 V. A. Magnotta, L. Friedman, and F. Birn, Measurement of Signal-to-Noise and Contrast-to-Noise in the fBIRN Multicenter Imaging Study, Journal of Digital Imaging, Vol 19, No 2 (June), 2006: pp 140-147

8 N. Hansen, A. Ostermeier, Adapting arbitrary normal mutation distributions in evolution strategies: the covariance matrix adaptation, in: In: Proceedings of IEEE International Conference on Evolutionary Computation, 1996, pp. 312–317, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICEC.1996.542381

9 Rapin J, Teytaud O. Nevergrad - A gradient-free optimization platform. https://GitHub.com/FacebookResearch/Nevergrad. 2018.

Figures

Figure 2: Results of live optimization in vivo using MR-double-zero sorted by loss. (First row) Resulting GRE images with parameters and loss as labels. (Second row) Losses for all 100 iterations sorted retrospectively. (Third row) Histograms on which the loss is determined by Hartigan’s dip test. Parameters to be optimized were flip angle (FA in degree), echo time (TE in ms) and repetition time (TR in ms).