0533

Semi-Randomized Trajectories to the Rescue: Reducing Artifacts from Fluctuating Physiological Signals in 3D Steady-State MRI

Amir Seginer1 and Rita Schmidt2

1Siemens Healthcare Ltd, Rosh Ha'ayin, Israel, 2Department of Brain Sciences, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel

1Siemens Healthcare Ltd, Rosh Ha'ayin, Israel, 2Department of Brain Sciences, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel

Synopsis

Keywords: Data Acquisition, Artifacts, ultra-high field

Rapid 3D steady-state sequences such as SWI are sensitive to semi-periodic physiological fluctuations (e.g., cardiac pulsation, breathing, and eye movement) resulting in repeating artifacts in the images. Randomization of the phase-encoding order reduces the above artifacts but results in apparent noise from slow global changes (like motion or eddy currents changes). We propose a new semi-randomized acquisition order that allows to set a cutoff frequency for artifact suppression; above which artifacts are suppressed, whereas artifacts from slower changes are unaffected. Simulations and SWI human brain scanning at 7T validate the method.

Introduction

Rapid steady-state sequences offering 3D acquisitions and multiple contrasts1 are widely used. These sequences are, however, sensitive to semi-periodic physiological fluctuations of the signal and/or its phase, e.g., from cardiac pulsation in the blood vessels (0.3-1 Hz), breathing (0.7-2 Hz), and eye/eyelids movement (0.25-0.33 Hz). The semi-periodicity results in incorrect interpretation of the signal’s source location, manifested as repeating artifacts in the image whose intensity depends on the scan parameters (like TR and flip angle). Susceptibility Weighted Imaging (SWI) that utilizes the benefits of a 3D steady-state acquisition with short TR is widely used, but is also very sensitive to the above artifacts.Here we examine how by simply reordering the phase encodes (PEs) of the acquisition one can reduce the artifacts from local fluctuations, as long as the source of the fluctuating signal is small. We pick up on previous works2-8 considering random and semi-random acquisition ordering to suppress the above artifacts. A randomized order can suppress any repeating artifact but it may also increase the apparent noise, e.g., in cases of slow movement of the subject or slow changes due to eddy currents. Here we propose a new semi-randomized space-filing curve that allows to set a cutoff frequency for artifact suppression. Thus, fluctuations above the cutoff are suppressed, whereas changes from slow movement are not affected. We examine and characterize the above methods using simulations and SWI human scanning at 7T including parallel imaging (using a Cartesian acquisition).

Methods

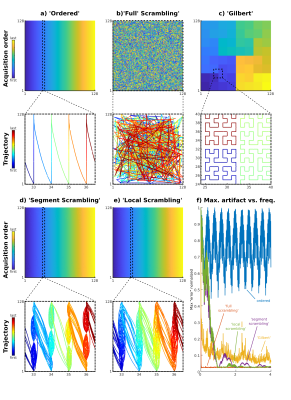

Five ordering schemes were tested in simulation and in vivo:- 'Ordered' - The standard order, sequentially going through a 2D phase encoding grid (column by column, or row by row).

- 'Full Scrambling' - Random shuffling of all the possible PEs.

- 'Gilbert' - A generalized version of the Hilbert curve, supporting rectangular domains9.

- 'Segmented Scrambling' - Targeted at modulations faster than a cutoff frequency $$$f_\mathrm{cutoff}$$$. The ordered set is treated as a 1D array, split into segments of length $$$1/(\mathrm{TR}\cdot{f_\mathrm{cutoff}})$$$ and each, independently, randomly permuted. [In practice, segments where not of identical length, as integer lengths are involved.]

- 'Local Scrambling' - A random shuffling aiming to mimic the time shift distribution of Segmented Scrambling but without using explicit segments. (For the target cutoff, an effective cutoff $$$f_\mathrm{cutoff}/1.2$$$ was used.)

In vivo scans were performed on a 7 T system (MAGNETOM Terra, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen) using a modified GRE sequence that allows arbitrary ordering of the PE lines and an option to interleave two orderings. Interleaving two orderings allows a simultaneous acquisition of both and thus a comparison at the same conditions. See figures for scan parameters.

Results

Fig. 1 shows the examined orderings and compares the intensity of the worst “artifact” as a function of modulation frequency. The effect of the TR, of the number of PE samples ($$$N_\mathrm{tot}$$$), and of the cutoff $$$f_\mathrm{cutoff}$$$ on the worst artifacts is shown in Fig. 2. Fig. 3 shows the effect of the size of the modulating object on the resulting “noise”. In vivo results comparing the different ordering schemes are shown in Fig. 4, each acquired interleaved with the Ordered scheme. Fig. 5 shows an in vivo example demonstrating movement and breathing artifacts. This case emphasizes that Full Scrambling may increase the overall noise in the image while Local Scrambling still provides a good quality image.Discussion

As expected, Full Scrambling minimizes the artifact from a periodic signal (except at extreme modulation frequencies of $$$\sim1/(\mathrm{scan\ time})$$$ and $$$\sim1/\mathrm{TR}$$$). However, Full Scrambling involves large steps in k-space which have led to their own artifacts (affected also by the readout bandwidth, but not shown here). A Hilbert-like curve minimizes the PE k-space steps but suppresses the artifact less effectively (Figs. 1, 4) and in addition is more difficult to implement for non-uniform sampling, e.g., GRAPPA with its center of k-space fully sampled.Local Scrambling, however, benefits from both worlds. K-space steps are limited in size and the suppression of the artifacts practically matches that of Full Scrambling for frequencies above $$$f_\mathrm{cutoff}$$$. In this approach, the lower frequency modulations (typically associated with global motion, e.g., head motion) are hardly affected, thus no extra noise appears (Fig. 5). The scrambling approach benefits from 3D acquisitions and increasing resolution since the artifact magnitude depends on the total number of PE samples, behaving like $$$\sim1/\sqrt{N_\mathrm{tot.}}$$$.

Conclusions

Local Scrambling of steady-state acquisitions, especially 3D with high resolution, achieves a significant reduction of artifacts arising from semi-periodic localized fluctuations. This is especially useful in SWI which is sensitive to fluctuations in blood vessels and the eyes. The method was demonstrated with high resolution SWI brain imaging at 7T MRI. Global changes (motion or phase) still require complementary corrections.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

- Hargreaves BA. Rapid gradient-echo imaging. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 2012;36:1300–1313.

- Bailes DR, Gilderdale DJ, Bydder GM, Collins AG, Firmin DN. Respiratory ordered phase encoding (ROPE): a method for reducing respiratory motion artefacts in MR imaging. Journal of Computer Assisted Tomography 1985;9:835–838.

- Haacke ME, Patrick JL. Reducing motion artifacts in two-dimensional Fourier transform imaging. Magnetic Resonance Imaging 1986;4:359–376.

- Korin HW, Riederer SJ, Bampton AEH, Ehman RL. Altered phase-encoding order for reduced sensitivity to motion in three-dimensional MR imaging. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 1992;2:687–693.

- Wilman AH, Riederer SJ. Improved centric phase encoding orders for three-dimensional magnetization-prepared MR angiography. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 1996;36:384–392.

- Jhooti P, Wiesmann F, Taylor AM, Gatehouse PD, Yang GZ, Keegan J, Pennell DJ, Firmin DN. Hybrid ordered phase encoding (HOPE): An improved approach for respiratory artifact reduction. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 1998;8:968–980.

- Parker DL, Goodrich KC, Roberts JA, Chapman BE, Jeong EK, Kim SE, Tsuruda JS, Katzman GL. The need for phase-encoding flow compensation in high-resolution intracranial magnetic resonance angiography. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 2003;18:121–127.

- Wermer MJH, van Walderveen MAA, Garpebring A, van Osch MJP, Versluis MJ. 7 Tesla MRA for the differentiation between intracranial aneurysms and infundibula. Magnetic Resonance Imaging 2017;37:16–20.

- Červený J, Generalized Hilbert ("gilbert") space-filling curve for rectangular domains of arbitrary (non-power of two) sizes. https://github.com/jakubcerveny/gilbert/blob/master/gilbert2d.py, accessed:2022.07.10.

Figures

Figure 1: Illustrative

comparison of the ordering schemes. (a)–(e) K-space (128 × 128) color coded according to the acquisition

order of the PE samples and a zoom-in, below each, showing the trajectory. The

trajectories are color coded according to the sampling times within

each zoom (using arced connectors

for better visualization). (f) The

normalized (worst) artifact from a point source vs. its modulation

frequency, plotted for each scheme. For illustration purposes, simulations used

128 × 128 PEs, TR 20 ms, and cutoff of 1 Hz (Local Scrambling used $$$f_\mathrm{cutoff}/1.2$$$).

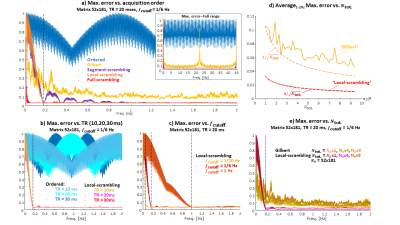

Figure 2: Dependence

of the worst artifact (from a modulating point source) on scan parameters and

ordering schemes. (a) All acquisition schemes for a typical set of

scanning parameters. (b) Effect of changing TR. (c) Effect of changing $$$f_\mathrm{cutoff}$$$. (d,

e) Effect of the total number of PE sampling points on the worst artifact

(Gilbert and Local Scrambling only): (d) Worst artifact as a function of $$$N_\mathrm{tot.}$$$, (e)

Worst artifact as function of the modulation frequency for three $$$N_\mathrm{tot.}$$$ values.

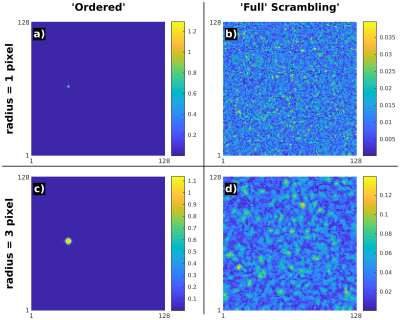

Figure 3: Qualitative

effect of source size on “noise” after Full Scrambling. Simulations for disks

of radius 1 pixel (top) and 3 pixels (bottom), using Ordered (left) and Full

Scrambling (right) schemes. Acquisition matrix 128 × 128, TR 20 ms, and modulation

frequency (of phase) 0.3Hz. The “noise” in the Full Scrambling case is a

convolution of a point source “noise” and the actual source. Thus, as the

source increases, the “noise” level increases and larger scale patterns appear.

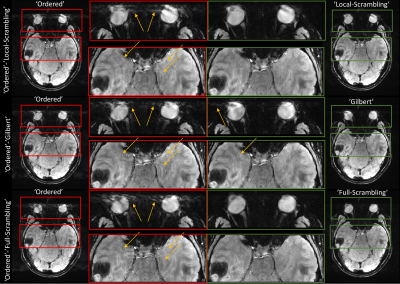

Figure 4: In

vivo comparison of the Ordered scheme (left half, red boxes) with Local Scrambling,

Gilbert, and Full Scrambling schemes

(right half, green boxes). Each

scan interleaved the Ordered scheme with a different one, to acquire them

simultaneously. Scan parameters: TR=22ms, TE=14ms, FOV 220×184 mm2,

in-plane resolution 0.55×0.55 mm2, slice thickness 2 mm,

acceleration ×2, $$$N_\mathrm{tot.}$$$ matrix=

52×181, transversal orientation, readout AP direction.

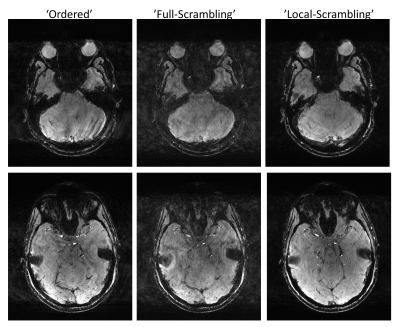

Figure 5: In vivo comparison of

the Ordered scheme with Full Scrambling and Local Scrambling, showing two

slices for each. This time scans were not interleaved, but repeated

scans showed similar results. Scan parameters: TR=22 ms, TE=14ms, FOV 220×184

mm2, in-plane resolution 0.55×0.55 mm2, slice thickness 2

mm, acceleration ×2, $$$N_\mathrm{tot.}$$$ matrix= 52×181, transversal orientation,

readout AP direction.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/0533