0531

SNR-efficient, motion-robust multi-echo SPGR with k-space aliasing

Peter J Lally1,2, Mark Chiew3, Paul M Matthews1,4, Karla L Miller5, and Neal K Bangerter6

1Department of Brain Sciences, Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom, 2Centre for Care Research and Technology, UK Dementia Research Institute, London, United Kingdom, 3Medical Biophysics, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, 4UK Dementia Research Institute at Imperial, London, United Kingdom, 5Wellcome Centre for Integrative Neuroimaging, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom, 6Department of Bioengineering, Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom

1Department of Brain Sciences, Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom, 2Centre for Care Research and Technology, UK Dementia Research Institute, London, United Kingdom, 3Medical Biophysics, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, 4UK Dementia Research Institute at Imperial, London, United Kingdom, 5Wellcome Centre for Integrative Neuroimaging, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom, 6Department of Bioengineering, Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: Data Acquisition, Pulse Sequence Design, SSFP, susceptibility

The behaviour of magnetisation under RF spoiling is typically considered to be pseudorandom from TR to TR. Here we describe a model for the coherent underlying phase behaviour which we exploit in a new acquisition strategy. We propose this as an SNR-efficient and motion-robust alternative to multi-echo spoiled gradient echo acquisitions.Introduction

In this work, we use quadratic RF spoiling to give a short-TR alternative to a traditional multi-echo RF- and gradient-spoiled gradient echo (SPGR) sequence. We hypothesised that the inherent signal averaging in the proposed approach would make it robust to artifacts when imaging an area such as the brainstem, which usually suffers from transient phase artifacts from pulsatile motion.Theory

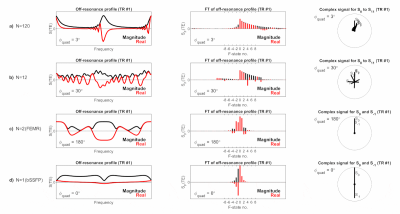

Gradient spoiling and k-space aliasingAt short TRs and in the absence of gradient spoiling, balanced steady state free precession (bSSFP) sequences have a characteristic periodic off-resonance profile resulting in banding artifacts. By introducing a large unbalanced gradient within the TR, the frequency variation becomes compressed in space until the bands are no longer visible because they are confined to a single voxel (Figure 1). In k-space, these repeating banding patterns correspond to a series of evenly-spaced signals (SF) that constitute the configuration states (F-states) in the extended phase graph formalism. By careful choice of the unbalanced gradient area, the signal components from higher order F-states can be pushed to a specific location in k-space (k-space aliasing1, Figure 1).

Linear phase cycling

One common method for controlling banding artifacts (e.g., in bSSFP) is to shift them across an image with a linear phase cycling scheme. Here, the nth RF pulse has phase $$$\phi_n=n\phi_{lin}$$$. To obtain a band-free image, a series of images can be acquired with different $$$\phi_{lin}$$$ and combined via e.g. sum-of-squares2. In k-space this is equivalent to rotating each F-state signal (SF) by a constant term: $$$e^{iF\phi_{lin}}$$$.

Quadratic phase cycling (RF spoiling)

Rather than linear phase cycling, quadratic phase cycling (RF spoiling) can be employed, with the nth RF pulse having phase $$$\phi_n=0.5\phi_{quad}n^2$$$. This has the effect of shifting the off-resonance profile from one TR to the next. In k-space, this is equivalent to a phase term for SF which increments with each RF pulse: $$$e^{inF\phi_{quad}}$$$.

An important feature of quadratic series is that they are N-periodic, where N=2π/$$$\phi_{quad}$$$ 3,4. Provided N is an integer the off-resonance profile is consistent after every Nth RF pulse. Figure 2 demonstrates the magnetisation behaviour for different N-periodic experiments, where N=120, N=12 (used in this work), N=2 (FEMR5), and N=1 (bSSFP).

Phase dependency in RF-spoiled sequences

At low flip angles and short-TRs, the magnitude of each F-state signal in an RF-spoiled sequence can be described as follows3: $$M_F(TE)=e^{-(TE+F\cdot TR)/T_2^*}sin\alpha\frac{1-e^{-TR/T_1}}{1-(cos\alpha) e^{-TR/T_1}}\tag1$$ Incorporating local off-resonance ($$$\omega$$$), the signal from each F-state at TE is given by: $$S_F(TE)=M_F(TE)e^{i\omega(TE+F{\cdot}TR)}\tag2$$ The measured signal in the nth TR is then the sum across all F-states after incorporating RF phase cycling: $$S(TE,n)=\sum_{F} S_F(TE)e^{iF(n\phi_{quad}+\phi_{lin})}\tag3$$ $$=e^{i\omega TE}\sum_{F}M_F(TE)e^{iF(\phi_{lin}+\omega TR)}e^{inF\phi_{quad}}\tag4$$ The phase terms in Equation 4 can be grouped into: i) a global term, $$$e^{i{\omega}TE}$$$ ; ii) a constant linear term, $$$e^{iF(\phi_{lin}+{\omega}TR)}$$$, causing a constant spatial shift in the off-resonance profile; and iii) an n-dependent linear term in F, $$$e^{inF\phi_{quad}}$$$, which causes a per-TR spatial shift in the off-resonance profile. From here onwards, we assume $$$\phi_{lin}$$$=0° for simplicity.

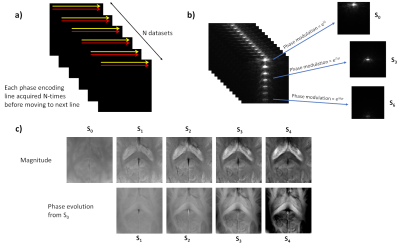

Equation 4 allows us to isolate N separate F-state signals due to their relative phase evolution across N measurements. Meanwhile, we can set the exact amount of gradient spoiling needed to ensure that only N or fewer states remain within the acquired k-space. This can all be determined a priori. A schematic of the acquisition and reconstruction scheme is shown in Figure 3.

The signal magnitude from higher order F-states is more heavily T2* weighted, and the phase is more susceptibility weighted (reflected in the F$$$\cdot$$$TR terms in Equations 1-2, Figure 3). For carefully chosen TR and TE, the SF signals therefore have relative weightings equivalent to the echo signals obtained from a long-TR multi-echo SPGR sequence. However, there is inherent averaging across the N-periodic states which may increase its robustness to transient phase fluctuations.

Methods

We performed an experiment on a 7T Siemens MAGNETOM Terra (Erlangen, Germany) with a 1Tx/32Rx head coil (Nova Medical, Wilmington, MA, USA). The proposed k-space-aliased SPGR sequence (kaSPGR1) was implemented with $$$\phi_{quad}$$$=30° to give a 12-periodic experiment with 7 directly measured F-states (S0 to S6), and compared to a matched multi-echo SPGR sequence with a longer TR and 7 TEs.In a first healthy volunteer we conducted a single-slice 2D experiment, where the flip angle was varied for each sequence to measure SNR efficiency. In two more healthy volunteers, we conducted 3D experiments covering a 2cm axial section across the brainstem.

Results and Discussion

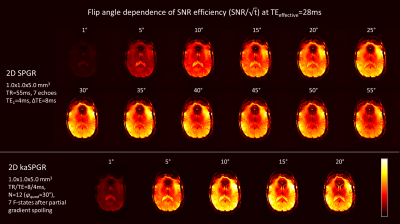

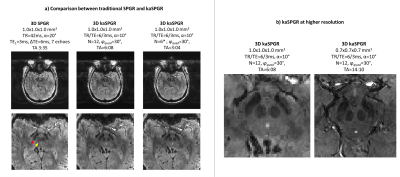

An SNR efficiency comparison is shown in Figure 4 for the 2D experiment with various flip angles. All images shown have an effective TE=28ms. kaSPGR appears to be more SNR efficient at the optimal flip angle (10-15°) compared to the equivalent long-TR SPGR (30-35°).Figure 5 shows reconstructed 3D data, highlighting iron-rich brainstem structures which are more conspicuous on kaSPGR images. We hypothesise that the proposed approach reduces the sensitivity to transient phase fluctuation caused by cardiac pulsation, due to averaging across N-periodic states during reconstruction.

Conclusions

The inherent phase behaviour of magnetisation under RF spoiling can be exploited to give an SNR-efficient and motion-robust alternative to multi-echo SPGR experiments. This could enable higher resolution T2*- or susceptibility-weighted imaging in areas such as the brainstem, where pulsatile motion can be otherwise problematic.Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr Iulius Dragonu (Siemens Healthineers) for providing support for sequence development, and the core team at the LoCUS 7T facility for their support with scanning. PJL acknowledges generous support from The Wellcome Trust (220473/Z/20/Z), The Edmond J Safra Foundation, UK Dementia Research Institute, NIHR Imperial Biomedical Research Centre, and National Institutes of Health (R01EB002524).References

1. Lally PJ, Chiew M, Statton B et al. (2022) SNR-efficient SSFP

with k-space aliasing. Proc. Intl. Soc. Mag. Reson. Med. 30:0503

2. Bangerter NK, Hargreaves BA, Vasanawala SS, et al. (2004) Analysis of multiple-acquisition SSFP.

Magn. Reson. Med., 51: 1038-1047.

3. Ganter C. (2006) Steady state of echo–shifted sequences with radiofrequency phase cycling. Magn. Reson. Med., 56: 923-926.

4.

Guo S and Noll DC. (2020) Oscillating steady-state imaging (OSSI): A novel method for functional MRI. Magn Reson Med., 84: 698– 712.

5. Vasanawala SS, Pauly JM and Nishimura DG. (1999) Fluctuating equilibrium MRI. Magn. Reson. Med., 42: 876-883.

Figures

Figure 1: Illustration

of the effect of gradient spoiling (with no RF spoiling, i.e. φn+1 = φn + const.).

Increasing the gradient spoiler (red) at the end of the TR will push F>0

components outside of the measured k-space, leading to a typical gradient

spoiled image. With a reduced gradient spoiler, we can directly measure

additional signal components (k-space aliasing), but they appear as banding

artifacts across the image.

Figure 2: Illustrating

examples of N-periodic steady states created by different quadratic spoiling

increments φquad.

The off-resonance profile (left) varies from TR-to-TR, with periodicity equal

to 2π/φquad. After Fourier transform (centre), this can be

modelled as a linear phase term which affects each F-state. This is most

clearly visible in the complex plane (right), where the phase of each signal

component (SF) is incremented by Fφquad after

every TR.

Figure 3: Illustrating the acquisition/reconstruction

process used. a) For a chosen N-periodic experiment, a single phase

encoding line was acquired for all N states before moving to the next line. b) With knowledge of the phase modulation of the

signal components across the N-states, they can be

extracted from the acquired data series. c) The magnitude and phase

of the data provide T2* and susceptibility weighting, respectively, as obtained in a multi-echo SPGR experiment.

Figure 4: Comparison of the SNR efficiency (i.e. SNR/√(time) )

for the symmetrically sampled S3 signal with T2* weighting

equivalent to a traditional SPGR with TE = 3xTR(kaSPGR) + TE(kaSPGR). kaSPGR has higher SNR efficiency than a matched SPGR at

the optimal flip angle.

Figure 5: a) Volunteer

experiment with 3D matched kaSPGR and SPGR sequences (top row shows full FOV; bottom row shows same data zoomed on brainstem). kaSPGR more clearly shows

iron-rich nuclei such as the substantia nigra (red arrow, bottom row) and red

nucleus (yellow arrow, bottom row). All images have an effective TE=15ms. *Retrospective

subsampling of N=6 states from acquired N=12 data. b) kaSPGR imaging at different spatial resolutions in separate volunteers.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/0531