0514

Free-Breathing Dynamic Pancreatic MRI Using Stack-of-Stars Radial Sampling Algorithm and Compressed SENSE

Yoshifumi Noda1, Nobuyuki Kawai1, Tetsuro Kaga1, Kimihiro Kajita2, Yu Ueda3, Masatoshi Honda3, Fuminori Hyodo1,4, Hiroki Kato1, and Masayuki Matsuo1

1Department of Radiology, Gifu University, Gifu, Japan, 2Department of Radiology Services, Gifu University Hospital, Gifu, Japan, 3Philips Japan, Tokyo, Japan, 4Institute for Advanced Study, Gifu University, Gifu, Japan

1Department of Radiology, Gifu University, Gifu, Japan, 2Department of Radiology Services, Gifu University Hospital, Gifu, Japan, 3Philips Japan, Tokyo, Japan, 4Institute for Advanced Study, Gifu University, Gifu, Japan

Synopsis

Keywords: Pancreas, Pancreas

Dynamic contrast-enhanced imaging is an essential examination in pancreatic MRI. However, non-diagnosable image quality due to motion artifacts and inappropriate scan timing for pancreatic phase are common problems. Recently, free-breathing sequence (4D FreeBreathing) has been introduced and it can provide diagnosable image quality even in free-breathing. In this study, we evaluated the feasibility of 4D FreeBreathing in pancreatic MRI. Our results showed that 4D FreeBreathing could provide diagnosable image quality and appropriate pancreatic phase scanning could be achieved in all examinations.Purpose

Dynamic contrast-enhanced imaging needs multiple breath-holds; however, degraded image quality is often observed due to its susceptibility to body motion. Additionally, it often suffers from inappropriate scan timing for pancreatic phase. To address those issues free-breathing sequence (4D FreeBreathing) has been introduced and the clinical usefulness has been reported1. Recently, a prototype 4D FreeBreathing that can be used in combination with Compressed SENSE has been developed to enable further acceleration and improve image quality. In the present study, we attempt to evaluate the feasibility of 4D FreeBreathing in pancreatic protocol MRI and compare it with a conventional breath-holding sequence.Materials and Methods

This prospective study was approved by our Institutional Review Board, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Six participants (1 man and 5 women, median age, 72 years; interquartile age range, 69–75 years) with suspected pancreatic diseases underwent free-breathing dynamic pancreatic MRI between April 2022 and September 2022 were included (4DFB group). We also included 15 patients who underwent breath-holding dynamic pancreatic MRI during the same period (eTHRIVE group). Using a 3T MRI scanner (Ingenia 3.0T CX; Philips Healthcare) equipped with a 32-channel digital coil, we performed dynamic contrast-enhanced pancreatic MRI. Scanning parameters were as follows: repetition time/echo time, 4.0/1.86 msec; flip angle, 12 degrees; acquisition voxel size, 1.56 × 1.56 × 4.00 mm3; field of view, 40 × 40 cm2; the number of slices, 100; CS factor, 2.0 (in-plane)/2.0 (through-plane). Multiphasic imaging was immediately started after the start of contrast agent administration. The scan duration of 3 minutes was required to capture the pancreatic and portal venous phases. A footprint of 30 seconds and temporal resolution of 10 seconds were used in this study. Gadobutrol (Gadovist®; Bayer Healthcare) was used as contrast agent for all cases. Before the image analyses, the study coordinator selected the optimal images for the pancreatic and portal venous phases. A radiologist, who was unaware of the scan sequence, randomly reviewed the images at precontrast, pancreatic, and portal venous phases and assigned confidence scores for motion, streak, pancreatic sharpness, overall image quality using a 5-point scale. Diagnosable image quality was defined as ≥ 3 points in the overall image quality. Furthermore, a radiologist assessed whether the scan timing of the pancreatic phase was appropriate or not. A radiologist also measured mean signal intensity using region-of-interests (ROIs) placing on the pancreas (SIpancreas) and paraspinal muscle (SImuscle). Standard deviation (SDpancreas) was also determined by placing an ROI on the pancreas. The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) were calculated as SIpancreas/SDpancreas and (SIpancreas – SImuscle)/SDpancreas, respectively. The Mann-Whitney U test was conducted to compare the qualitative and quantitative parameters between eTHRIVE and 4DFB groups. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered to be significant.Results

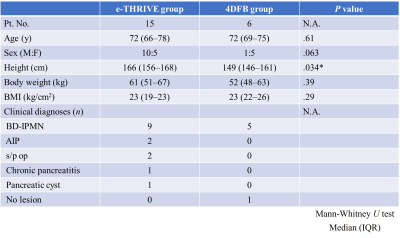

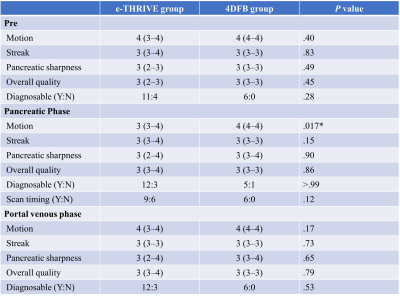

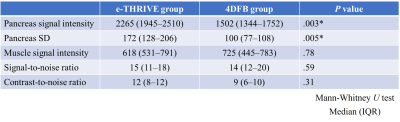

Patients’ demographics are summarized in Table 1. Patients’ height was higher in eTHRIVE group than in 4DFB group (P = .03). No difference was found all other parameters between the two groups (P = .063–.61). Median confidence score for motion at pancreatic phase was higher in 4DFB group than in eTHRIVE group (P = .02). No difference was found in all other parameters between the two groups (P = .12–.90). All of 6 examinations in 4DFB group showed appropriate scan timing for pancreatic phase (Table 2, Figure 1). The median SIpancreas (P = .003) and SDpancreas (P = .005) were higher in eTHRIVE group than in 4DFB group. No difference was found in other parameters between the two groups (P = .31–.78) (Table 3).Discussion

4D FreeBreathing is composed of three essential features. First, a variable-density golden angle stack-of-stars2 is used. This technique can optimize 3D sampling by having a high-density radial grid in central k-space and adjusting lower densities at the periphery. As a result, acquisition time can be reduced due to less spokes. Second, 4D k-space weighted image contrast (KWIC) sliding window reconstruction3 is applied. To improve temporal resolution, small data acquisition is needed. However, this leads streak artifact, therefore view sharing technique is used. The KWIC filter enhances the data during desired phase in k-space center. Lastly, respiratory soft gating is used. This allows to reduce streaking by weighting spokes based on their respiratory state. The weighted reconstruction is performed in k-space center using data obtained during expiration. We believe that 4D FreeBreathing could provide diagnosable image quality by the contribution of these features. The timing of the pancreatic phase is crucial in pancreatic imaging. However, correct timing is challenging because the optimal time interval is short, and the amount of contrast agent is small. However, the dynamic scanning starts at the same time of contrast injection and continuously performed during the pancreatic phase in 4D FreeBreathing. In addition to this, the high temporal resolution allows to absolutely obtain appropriate pancreatic phase images. Although no statistical difference was observed in the proportion of appropriate scan timing, only 60% of examinations showed appropriate scan timing in eTHRIVE group against 100% in 4DFB group. We strongly believe that we will observe statistical difference between these two groups by accumulation of cases.Conclusion

4D FreeBreathing was feasible in dynamic pancreatic MRI and provided appropriate pancreatic phase in all examinations.Acknowledgements

The authors of this manuscript declare no relationships with any companies whose products or services may be related to the subject matter of the article.References

1. Endler CH, Kukuk GM, Peeters JM, Beck GM, Isaak A, Faron A et al.: Dynamic liver magnetic resonance imaging during free breathing: A feasibility study with a motion compensated variable density radial acquisition and a viewsharing high-pass filtering reconstruction. Invest Radiol 2022; 57: 470-477.

2. Winkelmann S, Schaeffter T, Koehler T, Eggers H, Doessel O: An optimal radial profile order based on the golden ratio for time-resolved mri. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2007; 26: 68-76.

3. Song HK, Dougherty L: K-space weighted image contrast (kwic) for contrast manipulation in projection reconstruction mri. Magn Reson Med 2000; 44: 825-832.

Figures

Table 1: Patients' demographics

Table 2: Qualitative image analysis

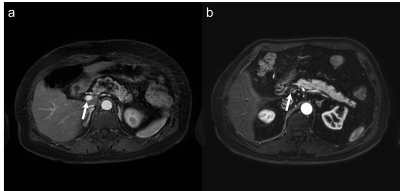

Figure 1: (a) 4D FreeBreathing image in a 69-year-old woman with

pancreatic cyst at pancreatic body shows portal venous inflow (arrow) and this

is appropriate scan timing for pancreatic phase. (b) Conventional eTHRIVE image in a 78-year-old man shows weak

portal enhancement and this is inappropriate scan timing.

Table 3: Quantitative image analysis

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/0514