0497

Reconstruction of High-Resolution Metabolite Maps from Noisy MRSI Data by Incorporating Spatiospectral Constraints through Learned Kernels1Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL, United States, 2National Center for Supercomputing Applications, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL, United States, 3Radiology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States, 4Radiology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, United States, 5Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL, United States, 6School of Biomedical Engineering, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China, 7Department of Bioengineering, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL, United States, 8Carle Illinois College of Medicine, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Spectroscopy, Image Reconstruction

High-resolution MR spectroscopic imaging (MRSI) suffers from very low signal-to-noise ratio, which is often addressed using a priori information/constraints. Existing constrained reconstruction methods utilize spectral constraints in the form of spectral subspaces/manifolds, while impose spatial constraints though spatial regularization. This paper presents a novel kernel-based partial separability model for reconstruction of high-resolution of metabolite maps from noisy MRSI data. The proposed model uses spectral basis functions to absorb spectral prior and a learned kernel function to absorb spatial prior. Experimental results demonstrated very encouraging reconstruction performance.Introduction

A fundamental challenge in achieving high-resolution MR spectroscopic imaging (MRSI) is low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). Constrained reconstruction has been recognized as a promising approach that utilizes a priori spectral and/or spatial information to reduce image noise. Recent research efforts have been mainly focused on exploiting spectral priors such as linear subspaces and nonlinear manifolds1-3. Spatial priors have been less investigated, with most existing methods imposing weak spatial constraints through spatial regularization4. In this work, we present a new method to effectively incorporate both spatial and spectral priors. This method is built upon a previously proposed kernel-based method5, but significantly extends it by learning an optimal kernel functional through deep networks. Compared to handcrafted kernel functions, learned kernels led to significantly improved reconstruction accuracy and robustness as demonstrated by our experimental results.Methods

Kernel-based partial separability modelIn this work, the desired MRSI image function is expressed as:

$$\hspace{10em}s\left(\boldsymbol{x}_n,t_m\right)=\sum_{\ell=1}^{L}{c_\ell\left(\boldsymbol{x}_n\right)\psi_\ell\left(t_m\right)},\text{ }n=1,2,\ldots,N\text{ and }m=1,2,\ldots,M\\\hspace{11em}\text{subject to }\|c_{\ell}(\boldsymbol{x}_n)-\sum_{i=1}^{N}a_{\ell,i}k(\boldsymbol{f}_i,\boldsymbol{f}_n)\|_2^2\leq\delta^2.\hspace{10em}(1)$$

This model has three important features. First, the model represents the spatiotemporal function as a low-dimensional subspace, exploiting the partial separability of MRSI signals6. Second, the temporal basis functions, $$${\psi_\ell\left(t_m\right)}$$$, are pre-learned from physics-based and data-driven spectral priors as done in7,8, leading to a significant reduction in degrees-of-freedom. Third, the spatial coefficients, $$${c_\ell\left(\boldsymbol{x}_n\right)}$$$, are approximated by a kernel-based model: $$$\sum_{i=1}^{N}{a_{\ell,i}k(\boldsymbol{f}_i,\boldsymbol{f}_n)}$$$. Here, $$$k(\cdot,\cdot)$$$ denotes a reproducing kernel function and $$$\boldsymbol{f}_{i}$$$ the image features extracted from the water images (e.g., those obtained from a reference scan or the companion water images in non-water-suppressed MRSI). This kernel model, motivated by the “kernel trick” in machine learning, was “trained” to absorb the side information from water protons to constrain the spatial variations of other molecules5.

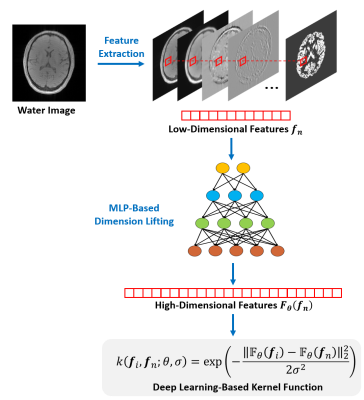

Neural network-based kernel functional learning

In the previous work5, the kernel function was constructed empirically using handcrafted functional forms (e.g., radial Gaussian kernel). In this work, we propose to use a neural network to represent and learn an optimal kernel function from training data (as illustrated in Fig. 1). More specifically, we express the desired kernel function as follows:

$$\hspace{10em}k\left(\boldsymbol{f}_i,\boldsymbol{f}_n;\theta,\sigma\right)=\exp\left(-\frac{\left\|\mathbb{F}_{\theta}(\boldsymbol{f}_i)-\mathbb{F}_{\theta}(\boldsymbol{f}_n)\right\|_2^2}{2\sigma^2}\right).\hspace{10em}(2)$$

The functional form of Eq. (2) is similar to the classic radial Gaussian kernel but different in two key aspects. First, the proposed functional is embedded with a multi-layer perceptron, $$$\mathbb{F}_{\theta}(\cdot)$$$, which explicitly lifts the original image feature, $$$\boldsymbol{f}_n$$$, from a low-dimensional space ($$$\mathbb{R}^{12}$$$) to a high-dimensional one ($$$\mathbb{R}^{512}$$$). This feature lifting strategy follows the spirit of “kernel trick”. With the learned kernel, $$$c_\ell\left(\boldsymbol{x}_n\right)$$$, viewed as a complex nonlinear function of $$$\boldsymbol{f}_n$$$, can be effectively represented as a linear function in the high-dimensional space to which $$$\boldsymbol{f}_n$$$ is lifted. Second, instead of manually selecting the parameters of the kernel function as in5, we learned the parameters based on training data. Particularly, we determined both $$$\theta$$$ and $$$\sigma$$$ by solving the following optimization problem:

$$\hspace{10em}\min_{\theta,\sigma}\mathbb{E}\left\|c_\ell\left(\boldsymbol{x}_n\right)-\sum_{i=1}^{N}{{\hat{a}}_{\ell,i}(\theta,\sigma)k(\boldsymbol{f}_i,\boldsymbol{f}_n;\theta,\sigma)}\right\|_2^2,\hspace{10em}(3)$$

where $$$\mathbb{E}$$$ denotes the expectation with respect to training samples, $$$c_\ell\left(\boldsymbol{x}_n\right)$$$ the ground truth spatial coefficients, and $$${\hat{a}}_{\ell,i}(\theta,\sigma)$$$ the optimal kernel coefficients in the $$$L_2$$$-sense. The problem in Eq. (3) was solved using the ADAM algorithm with a learning rate of 10-4.

Constrained MRSI reconstruction

With the proposed signal model and learned kernel function, image reconstruction was done by solving the following regularization problem:

$$\hspace{10em}C^*=\arg\min_{C}\left\|\boldsymbol{d}-\Omega F_BC\Psi\right\|_2^2+\lambda\left\|\left(I-KK^\dagger\right)C\right\|_2^2,\hspace{9em}(4)$$

where $$$\boldsymbol{d}$$$ denotes the measured MRSI data, $$$\Omega$$$ the sampling operator, $$$F_B$$$ the Fourier encoding operator including the $$$B_0$$$ inhomogeneity, $$$I$$$ the identity matrix, and $$$C, \Psi, K$$$ are matrices formed by the spatial coefficients, temporal basis functions, and kernel functions, respectively. In Eq. (4), the first term preserves the data consistency, while the second term imposes spatiospectral constraints. Once $$$C^*$$$ is determined, the final reconstruction of the desired spatiotemporal function was obtained as $$$\rho=C^*\Psi$$$.

Results

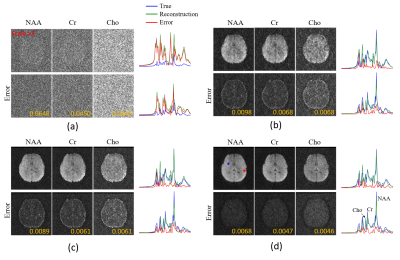

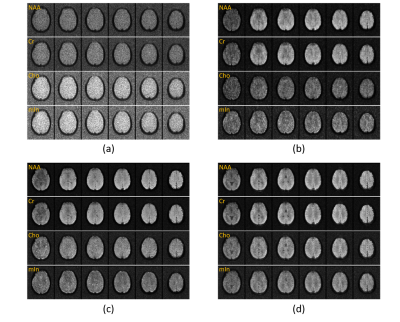

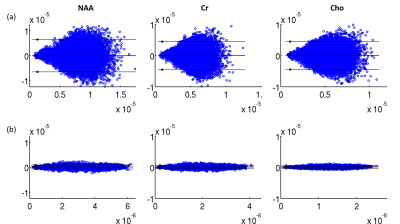

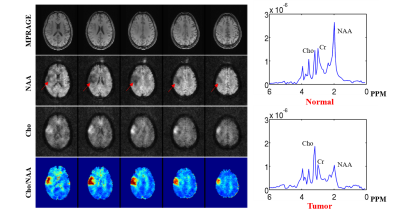

The proposed method has been validated using both simulated and experimental data. Simulated data were constructed based on Eq. (1) plus Gaussian noise. In vivo experimental data were obtained using the SPICE sequence9 with the following parameters: TR/TE=160/1.6 ms, 230×230×72 mm3 FOV, and 78×122×24 matrix size. For all experiments, the kernel function was trained using high-SNR data acquired by a hybrid FID/SE MRSI sequence with multiple averages10. Figure 2 shows some representative simulation results that compare the proposed method to other existing methods, including subspace projection (i.e., directly projecting the spatiotemporal distributions onto $$${\psi_\ell\left(t_m\right)}$$$), edge-preserving spatially regularized method, and previously proposed handcrafted kernel-based method. As can be seen, the proposed method achieved a significantly higher reconstruction accuracy. Figure 3 shows a set of in vivo results obtained from one healthy volunteer, while Figure 4 shows the reproducibility study results conducted on another subject. As can be seen, the proposed method significantly improved the quality and repeatability of the obtained metabolite maps. We have also evaluated the proposed method on a brain tumor data. As shown in Fig. 5, the proposed method successfully captured the metabolic abnormality within the lesion.Conclusions

This paper presents a novel kernel-based partial separability model for reconstruction of high-resolution metabolite maps from noisy MRSI data. The proposed model uses spectral basis functions to absorb spectral prior and the learned kernel function to absorb spatial prior. Reconstruction results from both simulated and experimental data demonstrated very promising potential of using the proposed method to support practical MRSI applications.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

[1] F. Lam and Z.-P. Liang, “A subspace approach to high-resolution spectroscopic imaging,” Magn Reson Med, vol. 71, no. 4, pp. 1349–1357, 2014.

[2] F. Lam, Y. Li, and X. Peng, “Constrained Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopic Imaging by Learning Nonlinear Low-Dimensional Models,” IEEE Trans Med Imaging, vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 545–555, 2020.

[3] Y. Li et al., “Machine learning-enabled high-resolution dynamic deuterium MR spectroscopic imaging,” IEEE Trans Med Imaging, vol. 40, pp. 3879-3890, 2021.

[4] J. P. Haldar, D. Hernando, S.-K. Song, and Z.-P. Liang, “Anatomically constrained reconstruction from noisy data,” Magn Reson Med, vol. 59, no. 4, pp. 810–818, 2008.

[5] Y. Li, F. Lam, B. Clifford, R. Guo, X. Peng, and Z.-P. Liang, “Constrained MRSI reconstruction using water side information with a kernel-based method,” in Proc. Intl. Soc. Magn. Reson. Med., 2018, p. 540.

[6] Z.-P. Liang, “Spatiotemporal Imaging with Partially Separable Functions,” in Proc. IEEE Int. Symp. Biomed. Imag., vol. 2, pp. 988–991, 2007.

[7] Y. Li, F. Lam, B. Clifford, and Z.-P. Liang, “A subspace approach to spectral quantification for MR spectroscopic imaging,” IEEE Trans Biomed Eng, vol. 64, no. 10, pp. 2486–2489, 2017.

[8] F. Lam, Y. Li, R. Guo, B. Clifford, and Z. Liang, “Ultrafast magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging using SPICE with learned subspaces,” Magn Reson Med, vol. 83, no. 2, pp. 377–390, 2020.

[9] X. Peng, F. Lam, Y. Li, B. Clifford, and Z.-P. Liang, “Simultaneous QSM and metabolic imaging of the brain using SPICE,” Magn Reson Med, vol. 79, no. 1, pp. 13–21, Jan. 2018, doi: 10.1002/mrm.26972.

[10] Y. Zhao, Y. Li, J. Xiong, R. Guo, Y. Li, and Z.-P. Liang, “Rapid high-resolution mapping of brain metabolites and neurotransmitters using hybrid FID/SE-J-resolved spectroscopic signals,” 2020.

Figures