0488

Functional Activation Pattern to varied working memory loads in Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Patients1Department of Diagnostic Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, University of Maryland Baltimore, Baltimore, MD, United States, 22National Intrepid Center of Excellence, Walter Read National Military Medical Center, Rockville, MD, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Data Analysis, Traumatic brain injury

Mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) account for 85% of all TBIs. Working memory impairment is one of the most common symptoms in mTBI patients and may persist years post-mTBI. In this study, we used N-back fMRI to investigate the varying N-back task loads on the functional activation pattern in patients with mild TBI and age-matched healthy controls (HCs) as well as the longitudinal changes within mTBI group. Our results suggested that appropriate task load would be more sensitive in detecting the subtle brain functional changes, even though differences in behavioral performance between mTBI and HCs were absent.Introduction

Mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) is one of the most prevalent neurological disorders and account for 85% of all TBIs [1]. One of the most common symptoms in mTBI patients is working memory impairment which may persist years post-mTBI [2]. The N-back fMRI is likely the most popular measures of working memory. Despite growing literature on the use of N-back test among TBI patients, no clear picture has emerged between the performance on N-back test and the corresponding functional activation patterns in mild TBI. A clear understanding of this relationship may provide better characterization of mTBI subjects particularly when no cognitive differences are observed between the mTBI patients and control subjects. In this study, we investigated various N-back task loads effects on the functional activation pattern in patients with mTBI compared with Healthy Controls (HCs), as well as longitudinal changes within mTBI group.Methods

Subjects: Thirty-five patients with mTBI (21males/14females, age of 46.46+/-15.89 years) were included in this study. All mTBI patients underwent cognitive behavioral test and N-back fMRI scans at post-1month and post-6month injury. A cohort of 28 age-matched HCs also included.Behavioral Test: The level of cognitive functioning was assessed by administering the Military Acute Concussion Evaluation (MACE) to each participant [3]. Self-reported symptoms were collected using the Modified Rivermead Post Concussive Questionnaire (RPQ) for mTBI patients [3]. Independent two-sample T-test was used to assess the difference in demographic and behavioral scores between the HC and mTBI groups.

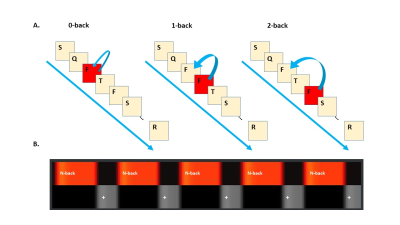

MRI Data Acquisition and Analysis: Three functional runs (0-, 1-, and 2-back) were acquired in order using a T2-weighted EPI sequence (TE/TR = 30 /2300 ms, resolution = 2.396 x 2.396mm2, slice thickness = 4mm). Each functional run consisted of 5 blocks of task (Figure 1). The task block consisted of the presentation of a sequence of letters and participants responded with a MR-compatible response box. Accuracy and average reaction time for correct response were calculated. The fMRI data were processed using SPM12. The preprocessing steps included slice timing, realignment, normalization to the MNI template, and spatially smoothed with an 8-mm FWHM. Statistical analyses were performed on individual data using the GLM, while group analyses were performed using a random-effects model. The significant level was defined as voxel-wise uncorrected p < 0.008 or p < 0.005 and cluster-wise FDR-corrected p < 0.05 for multiple comparison.

Results

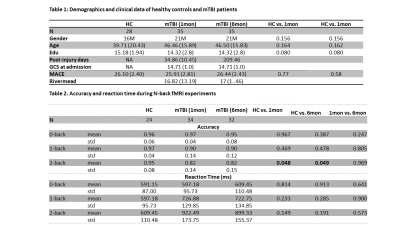

Table 1 shows that there was no significant difference in age, gender, education level, and MACE between the mild TBI and HC groups. There was no significant change across time in Rivermead score.Table 2 shows that accuracy was not significantly different between the HCs and mTBI groups for 0-back and 1-back tasks, but was significant for the more demanding 2-back task. The mean reaction time of correct response were not significantly different between groups and across time in mTBI group for all task loads.

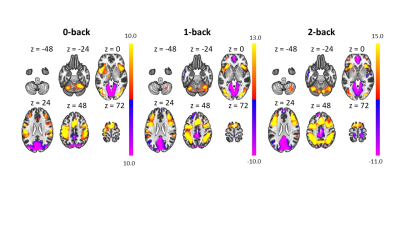

Figure 2 shows that the activation map of the three N-back loads for HCs and mTBI patients (N = 63). For all the three task loads, we observed consistent task positive brain regions in fronto-parietal network, cerebellum, and basal ganglia network, as well as task negative brain regions in default mode network (DMN).

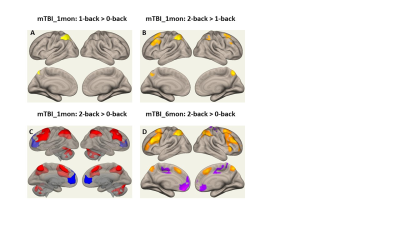

Figure 3 shows the activation difference maps among N-back task loads in mTBI group, whereas no significant activation difference was observed within HC group. For mTBI at post-1month, higher activation was found in left parietal when comparing 1-back with 0-back, in bilateral fronto-parietal network; when comparing 2-back with 1-back load, and in bilateral fronto-parietal network and bilateral cerebellum when comparing 1-back with 0-back load. For mTBI at post-6month, significant activation difference was observed only between 2-back and 0-back tasks with higher activation within the fronto-parietal network, and lower activation within the DMN.

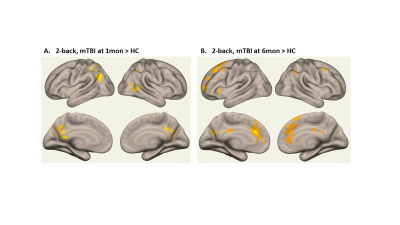

Figure 4 shows the group difference between HC controls and mTBI at post-1month and post-6month separately while the participants performed the 2-back task. The increased activation regions were also found within the fronto-parietal network. No group difference was found among the activation of 0-back and 1-back tasks. No significant longitudinal activation changes within the mTBI patients for all the three task loads.

Discussion

In this study, we used varying N-back fMRI to investigate functional activation difference in HC and mTBI groups, as well as longitudinal functional activation pattern changes in mTBI patients. Our results indicate similar accuracy between HCs and mTBI patients, a trend towards increased reaction time in mTBI patients, poorer cognitive performance assessment at the acute stage which recovered to the level of the HCs by the chronic stage. In terms of differences in functional networks, no differences were found between the HCs and mTBI subjects for the zero and 1-back tests. However, significant differences were observed on the 2-back task where mTBI patients had greater activation within the fronto-parietal network, basal ganglia and cerebellum. The default mode network was also suppressed only for the 2-back tests for mTBI patients. Our results suggested with appropriate working memory load, it would be able to detect subtle functional changes in mTBI patients, even though differences in behavioral performance between mTBI and HCs were absent.Acknowledgements

The study was conducted at University of Maryland School of Medicine Center for Innovative Biomedical Resources, Translational Research in Imaging @ Maryland (CTRIM) – Baltimore, Maryland. The study is supported by DOD grant W81XWH-08-1-0725 & W81XWH-12-1-0098, NIH grant 5R01NS105503, NIH grant 1F31NS081984.References

1. Cameron, K.L., et al., Trends in the incidence of physician-diagnosed mild traumatic brain injury among active duty U.S. military personnel between 1997 and 2007. J Neurotrauma, 2012. 29(7): p. 1313-21.

2. Arciniega, H., et al., Impaired visual working memory and reduced connectivity in undergraduates with a history of mild traumatic brain injury. Sci Rep, 2021. 11(1): p. 2789.

3. McCrea, M., et al., Standardized assessment of concussion (SAC): on-site mental status evaluation of the athlete. J Head Trauma Rehabil, 1998. 13(2): p. 27-35.

4. McDowell, S., J. Whyte, and M. D'Esposito, Working memory impairments in traumatic brain injury: evidence from a dual-task paradigm. Neuropsychologia, 1997. 35(10): p. 1341-53.

5. Yaple, Z. and M. Arsalidou, N-back Working Memory Task: Meta-analysis of Normative fMRI Studies With Children. Child Dev, 2018. 89(6): p. 2010-2022.

Figures