0484

Pseudo resting-state by task-evoked functional connectivity.

Alice Giubergia1, Sara Mascheretti2, Valentina Lampis3, Tommaso Ciceri1, Martina Villa4,5,6, Chiara Andreola7, Filippo Arrigoni8, and Denis Peruzzo1

1Neuroimaging Unit, IRCCS Eugenio Medea, Bosisio Parini (LC), Italy, 2Department of Brain and Behavioral Sciences, University of Pavia, Pavia (PV), Italy, 3Child Psychopathology Unit, IRCCS Eugenio Medea, Bosisio Parini (LC), Italy, 4Department of Psychological Sciences, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT, United States, 5Institute for the Brain and Cognitive Sciences (IBACS), University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT, United States, 6Haskins Laboratories, New Haven, CT, United States, 7Laboratoire de Psychologie de Développement et de l’Éducation de l’Enfant (LaPsyDÉ), Université Paris Cité, Paris, France, 8Paediatric Radiology and Neuroradiology Department, V. Buzzi Children’s Hospital, Milano (MI), Italy

1Neuroimaging Unit, IRCCS Eugenio Medea, Bosisio Parini (LC), Italy, 2Department of Brain and Behavioral Sciences, University of Pavia, Pavia (PV), Italy, 3Child Psychopathology Unit, IRCCS Eugenio Medea, Bosisio Parini (LC), Italy, 4Department of Psychological Sciences, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT, United States, 5Institute for the Brain and Cognitive Sciences (IBACS), University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT, United States, 6Haskins Laboratories, New Haven, CT, United States, 7Laboratoire de Psychologie de Développement et de l’Éducation de l’Enfant (LaPsyDÉ), Université Paris Cité, Paris, France, 8Paediatric Radiology and Neuroradiology Department, V. Buzzi Children’s Hospital, Milano (MI), Italy

Synopsis

Keywords: Data Processing, Brain Connectivity

Functional connectomics investigates how brain regions are functionally associated. Studies in literature seek to infer a “pseudo-resting” state from task data, however it should be tested whether resting-state-like connectivity can be inferred by task-fMRI data. This work investigates several preprocessings of task-evoked connectivity performing classification experiments, to test their ability to reproduce a real “resting-state” connectivity and their impact on a clinical context, namely the comparison of Typical Readers and Developmental Dyslexics. Our results suggest that a task-free “pseudo-resting” connectivity cannot be inferred from task-fMRI data and that signal preprocessing does not influence the way the classification rules are inferred.Introduction

Functional connectomics maps functional associations among brain regions, and it is typically based on resting-state fMRI1. However, due to practical limitations, many studies do not collect enough resting-state data2 and seek to infer a “pseudo-resting” state by task-modulated connectivity3. On the other hand, “task” connectivity enables to examine broader involvements of brain regions that might show modulated connectivity with other brain regions even though they are not activated during a task4. In this context, the comparison of connections between ROIs in “task” and “pseudo-resting” conditions may highlight the organization of the brain, thus the underpinning behavioural traits. The aim of the present study is two-fold: 1) to test whether a “pseudo-resting" state connectivity can be inferred and investigated even by task-fMRI data, and 2) to explore the way it affects subsequent analysis upon behavioural traits.Methods

Seventy-seven subjects (age range: 9-18 years, M/F: 49/28), 39 Typical Readers – TR and 38 with Developmental Dyslexia – DD) were administered with two visual tasks, i.e., Sinusoidal Gratings (SG) and Coherent Motion (CM), which elicit the dorsal stream pathway (both SG and CM) and the attention network (CM). fMRI BOLD time-series were processed with FreeSurfer to get “task” (i.e., without any task regression) and “pseudo-resting” (i.e., after task regression) conditions for both SG and CM and then sampled from the 360 cortical (HCP-MM1 atlas) and 18 deep Grey Matter (dGM) ROIs. Different task regression setups were tested varying the number of derivatives in the GLM’s HRF function, by which data were convoluted to get the neural response. Connectomes were portrayed by means of ROI-wise Pearson correlation of signal time-series. Since BOLD signals are influenced by a number of non-neural processes, the disposal of spurious connections is a crucial step in neuroimaging connectivity analysis, and thresholding is a popular procedure to sparse the connectivity matrices5 even though there is no gold standard algorithm to select the optimal threshold6. Therefore, we tested several sparsification thresholds. Multiple task classification experiments (i.e., SVM, Logistic Regression, Decision Tree, Random Forest, K-NN, Gaussian Naive Bayes, simple Multi-Layer Perceptron) were performed with a repeated Cross-Validation (CV) to evaluate the removal of task-related information in the “pseudo-resting” connectomes.Subsequently, we fixed the sparsity level (50%) and the derivatives for task regression (d=0), and performed a classification experiment with the aim of investigating the impact of task regression in the characterization of DD and TR. Group classification was performed with all connectomes (i.e., in both SG and CM task and in both “task” and “pseudo-resting” conditions) using a SVM classifier (C=1) with a 6-folding CV approach, and significance was tested with a 1000-permutations test.

In each fold of each experiment accuracy, AUC score, and the connections selected for the classification were saved to dig in the discriminative process. Connections selected in at least 5 folds out of 6 were identified as discriminative and compared between the 4 SVM experiments (i.e., task SG, task CM, “pseudo-resting” SG and “pseudo-resting” CM) dividing the number of shared connections by the maximum shareable connections between the 4 experiments. All connections were grouped by the belonging macro-ROIs as defined in the HCP-MMP1 atlas to get an overview of the areas devoted to the discrimination of DD and TR.

Results

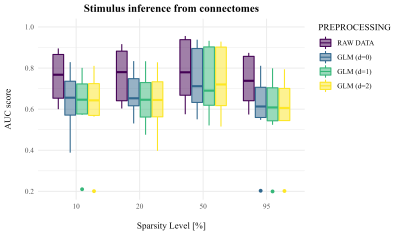

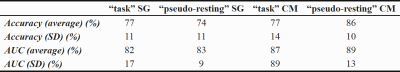

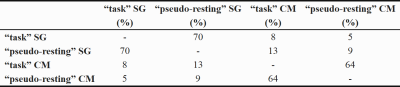

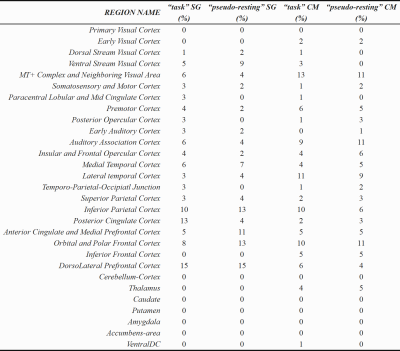

Figure 1 illustrates how task regression does remove task-related content from the fMRI signal, even though the stimulus can still be inferred from the derived connectomes independently of preprocessing (i.e., “task” or “pseudo-resting”). Table 1 reports the Cross-Validated metrics of the SVM experiments and suggests that classification of connectomes between DD and TR is successful in both “task” and “pseudo-resting” conditions. Very few connections are commonly selected by the classifiers working on SG and CM, either in “task” and “pseudo-resting”, while >60% of the connections are commonly selected when comparing “task” and “pseudo-resting” conditions in SG and CM (Table 2). From a macro-ROI point of view, Table 3 shows that the most involved macro-ROIs are known to be involved in DD, while the task-related differences can be associated with the distinct networks elicited by the two tasks.Conlusion and Discussion

In this work, preprocessing of task fMRI data was analysed to explore the contribution of the task information in connectomics. The successful discrimination of the task in “pseudo-resting” conditions indicates that connectomes preserve task information even after GLM regression, suggesting that a task-free “pseudo-resting” state cannot be inferred from task fMRI data, even if it can be inspected to study the context associated with DD not explicitly linked to the task-driven stimuli. Furthermore, discriminative connections depend on the type of task, which drives the way the classifier discriminates between DD and TR, as SG and CM share only few connections in both task and “pseudo” conditions. On the other hand, the greater intra-task and inter-processing coherence (i.e., a higher number of shared connections) shown in both SG and CM suggest that signal preprocessing does not influence the way the classification rules are inferred in the training, leading to similar evaluation of significant features.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Biswal BB, Mennes M, Zuo XN, et al. Toward discovery science of human brain function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(10):4734-4739. doi:10.1073/pnas.09118551072. Elliott ML, Knodt AR, Cooke M, et al. General functional connectivity: Shared features of resting-state and task fMRI drive reliable and heritable individual differences in functional brain networks. Neuroimage. 2019;189:516-532. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.01.068

3. Bhandari R, Kirilina E, Caan M, et al. Does higher sampling rate (multiband + SENSE) improve group statistics - An example from social neuroscience block design at 3T. Neuroimage. 2020;213. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.116731

4. Di X, Biswal BB. Toward Task Connectomics: Examining Whole-Brain Task Modulated Connectivity in Different Task Domains. Cerebral Cortex. 2019;29(4):1572-1583. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhy055

5. He Y, Evans A. Graph theoretical modeling of brain connectivity. Curr Opin Neurol. 2010;23(4):341-350. doi:10.1097/WCO.0b013e32833aa567

6. Ahmadi H, Fatemizadeh E, Motie-Nasrabadi A. Deep sparse graph functional connectivity analysis in AD patients using fMRI data. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2021;201. doi:10.1016/j.cmpb.2021.105954

Figures

Figure 1. Task discrimination (Coherent Motion - CM Vs Sinusoidal Gratings - SG) performances from connectome matrices among the different preprocessing techniques applying different GLM derivatives (i.e., no derivatives – RAW DATA, 0 derivative – GLM (d=0), 1 derivative – GLM (d=1), or 2 derivatives – GLM (d=2)) and levels of graphs’ sparsity (i.e., 10%, 20%, 50%, 95%).

Table 1. Behavioural trait (DD Vs TR) classification performances from connectome matrices. Experiments were performed using both “task” and “pseudo-resting” (d=0) derived connectomes with a of 50% sparsity level.

Table 2. Analysis of the overlap among connections chosen by the classifier in the different group classification experiments (i.e., DD Vs TR). The number of shared connections was divided by the maximum number of shareable connections between conditions.

Table 3. Analysis of the macro-ROI linked by the connections involved in the classification. For each classification experiment we report the ration of the selected connections linking the given marco-ROI.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/0484