0480

Improved NORDIC denoising for submillimetre BOLD fMRI using patch formation via non-local pixels similarity - pixel-matching (PM) NORDIC1Radiology, UMCU, Utrecht, Netherlands

Synopsis

Keywords: Data Processing, Data Processing, denoising, NORDIC, BOLD fMRI, thermal noise

Submillimetre BOLD fMRI enables studying brain function at the mesoscopic level but is limited by low SNR. The NORDIC PCA algorithm reduces thermal noise levels in fMRI in a patch-wise manner via singular value thresholding (SVT). However, the NORDIC patch formation uses adjacent pixels that often contain signals from multiple tissues, which can degrade the denoising performance. We propose an alternative patch formation using the similarity between non-local pixels, dubbed pixel-matching (PM) NORDIC. PM-NORDIC outperforms standard NORDIC in terms of temporal SNR and spatial smoothness estimates.INTRODUCTION

BOLD fMRI is an indispensable tool for depicting brain function. However, its low contrast-to-noise ratio and low SNR for high-resolution data limit its applicability and reliability1. Recently, Vizioli et al. (2021) introduced NOise Reduction with Distribution Corrected (NORDIC) PCA to attenuate thermal noise levels in fMRI via a principal component analysis (PCA) approach2. The algorithm divides the dataset into consecutive 4D (adjacent 3D spatial + 1D temporal) patches and denoises each patch by truncating the distribution of its singular values according to a parameter-free threshold. A potential downside of this patch formation through adjacent pixels is that the patches often contain signals from multiple tissues. Mixing of different tissues within a patch can negatively affect the identification of true signal components and may not exploit all information redundancy3,4,5. Zhao et al. (2022) introduced PCA-based denoising for diffusion MRI data by constructing patch matrices from similar non-local patches3,6,7. They argued that grouping similar patches exploits more information redundancy and promotes the low-rankness of the patch matrices, resulting in improved denoising for diffusion MRI. NORDIC denoising for BOLD fMRI utilizes signal redundancy over time and could thus also benefit from patch formation based on the non-local similarity of pixels2. Here, we apply an alternative patching method based on non-local pixel similarity (pixel-matching) for NORDIC (dubbed PM-NORDIC) on high-resolution fMRI data and show improved denoising compared to standard NORDIC in terms of temporal SNR (tSNR) and spatial smoothness estimates.METHODS

Imaging data: fMRI acquisitions were performed at 7T (Philips) using a 2x16-channel surface coil. A segmented 3D GE BOLD-EPI sequence was used, covering 40 coronal slices on the visual cortex with TR/TE=54/27ms, flipangle=20°, segments=3, SENSE factor (right-left, anterior-postior)=3.5/1.5, 0.55mm isotropic voxelsize, volumes=49, matrixsize=240x240.Standard NORDIC denoising: NORDIC uses locally low-rank (LLR) properties of image patches across image series. The algorithm divides the dataset into a series of 4D k x k x k x Q adjacent patches, where k stands for the dimensions of the spatial patch and Q is the number of time points. Here k=8 was used. Each patch is denoised via singular value thresholding (SVT) by cancelling the components indistinguishable from zero-mean Gaussian distributed noise (via Monte Carlo simulations), producing a noise-free low-rank approximation of the original noisy patch.

Proposed pixel-matching NORDIC: Here, patch formation occurs via grouping similar non-local pixels (Figure1). For each 2D slice, a number (N) of reference pixels are selected. Each reference pixel is compared to M neighbouring pixels to compute a similarity score based on the Frobenius norm between the pixel’s time series. The (k^2)-1 pixels exhibiting the highest similarity scores are vectorised and grouped with their reference pixel to form N Casorati matrices of (k^2) x Q elements (Figure1A). Finally, each Casorati matrix is denoised according to the standard NORDIC SVT and back distributed into image space (Figure1C).

Experiment design: In PM-NORDIC, the outcome of denoising highly depends on the patch size. A large patch size contains pixels with lower scores in the similarity ranking, thus results less homogenous compared to a smaller patch. Hence, we compared PM-NORDIC to standard NORDIC using two patch sizes: 1) the default computed by NORDIC (k x k x k x Q=8x8x8x49) when the user does not explicitly provide a specific patch size, and 2) a smaller patch of ([(k x k x k)^(⅓)]^2 x Q, i.e. 8x8x49)

Data analysis: The denoising performance was assessed by comparing tSNR and spatial smoothness estimates between standard NORDIC and PM-NORDIC. TSNR was computed by dividing the mean temporal signal by the temporal standard deviation pixel-wise. Smoothness was estimated through the degree of spatiotemporal autocorrelation (FWHM) using 3dFWHMx from AFNI using the ‘-ACF’, ‘detrend’ and ‘automask’ commands.

RESULTS

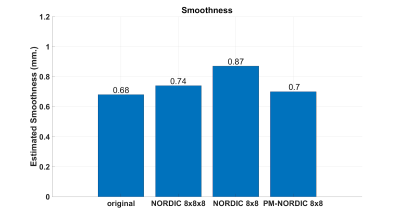

Compared to the non-denoised original data, the tSNR increased by a factor of 1.89, 2.2 and 2.5 for standard NORDIC with default patch size, for standard NORDIC with small patch size and PM-NORDIC, respectively (Figure2). Spatial smoothness increased by 11%, 30% and 7% for standard NORDIC with default patch size, standard NORDIC with small patch size, and PM-NORDIC, respectively (Figure3).DISCUSSION

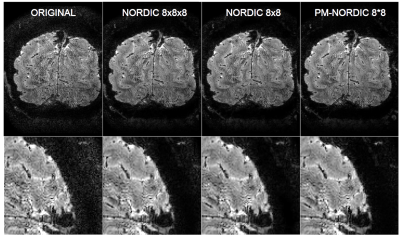

We introduced PM-NORDIC, an alternative patch formation approach for NORDIC PCA based on the similarity between non-local pixels3,6,7. PM-NORDIC showed improved tSNR and spatial smoothness scores for ~0.5mm isotropic BOLD fMRI data compared to standard NORDIC. Hence, homogenous patches are more easily low-rank approximated via SVT, leading to more effective denoising. Moreover, for PM-NORDIC, a small patch size signifies selecting fewer pixels along the similarity ranking, increasing the homogeneity of the resulting patch and further improving the denoising performance (Figure4,5). Finally, smoothness scores show that the proposed method better preserves structural detail than the default approach (Figure4,5). However, the pixel-matching approach acts on groups of non-local pixels. Therefore, adjacent pixels will unlikely be present in the same patch, leading to low levels of autocorrelation across the denoised image.CONCLUSION

The proposed PM-NORDIC denoising using patches of highly similar non-local pixels can boost denoising performance. PM-NORDIC led to substantial increases in tSNR and preservation of spatial smoothness. Reducing thermal noise contributions while preserving spatial integrity is essential for conducting BOLD fMRI at submillimeter resolutions, potentially revealing new neuroscientific insights at the mesoscopic scale2.Acknowledgements

Dr. Natalia Petridou for supplying high-resolution BOLD fMRI data.References

1. Logothetis, N. K. (2008). What we can do and what we cannot do with fmri. Nature, 453(7197), 869–878. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06976

2. Vizioli, L., Moeller, S., Dowdle, L., Akçakaya, M., De Martino, F., Yacoub, E., & Ugurbil, K. (2020). Lowering the thermal noise barrier in functional brain mapping with Magnetic Resonance Imaging. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.04.368357

3. Zhao, Y., Yi, Z., Xiao, L., Lau, V., Liu, Y., Zhang, Z., Guo, H., Leong, A. T., & Wu, E. X. (2022). Joint denoising of diffusion‐weighted images via structured low‐rank patch matrix approximation. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 88(6), 2461–2474.https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.29407

4. Veraart, J., Fieremans, E., & Novikov, D. S. (2015). Diffusion MRI noise mapping using random matrix theory. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 76(5), 1582–1593. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.26059

5. Veraart, J., Novikov, D. S., Christiaens, D., Ades-aron, B., Sijbers, J., & Fieremans, E. (2016). Denoising of diffusion MRI using random matrix theory. NeuroImage, 142, 394–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.08.016

6. Coupe, P., Yger, P., Prima, S., Hellier, P., Kervrann, C., & Barillot, C. (2008). An optimized blockwise nonlocal means denoising filter for 3-D Magnetic Resonance images. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, 27(4), 425–441. https://doi.org/10.1109/tmi.2007.906087

7. Dabov, K., Foi, A., Katkovnik, V., & Egiazarian, K. (2007). Image denoising by sparse 3-D transform-domain collaborative filtering. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing, 16(8), 2080–2095. https://doi.org/10.1109/tip.2007.901238

Figures

Fig 1. A) Flowchart of PM-NORDIC. For each 2D slice, reference pixels y0 are compared to M pixels ym. For each reference pixel, the (k2)-1 pixels with the highest similarity scores are grouped together with the reference pixel into a (k2)xQ Casorati matrix Y. The matrix undergoes NORDIC SVT to produce a denoised matrix X. B) patch-formation pixel weighting matrix for a 2D slice for standard NORDIC. C) patch-formation pixel weighting matrix for a 2D slice for PM-NORDIC.

Fig 2. Mean tSNR scores for a representative slice. The proposed PM-NORDIC further increases tSNR compared to standard NORDIC, especially in central areas of the brain where the g-factor amplification is usually higher (and thus higher thermal noise).

Fig 3. Spatial smoothness estimates (using 3dFWMHx AFNI) for a representative dataset. The proposed PM-NORDIC barely affects the original spatial smoothness of the dataset, indicating improved preservation of structural detail and potentially spatial specificity of functional BOLD activity compared to standard NORDIC.

Fig 5. Magnitude images and zoomed view of a representative slice before and the after denoising. PM-NORDIC effectively removes thermal noise without interfering with the structural information.