0477

Targeted Gastric Electrical Stimulation Modulates Functional Connectivity of the Interoceptive Network in the Rat Brain1Biomedical Engineering, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, United States, 2Biomedical Engineering, Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University, Dammam, Saudi Arabia, 3Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Data Analysis, Animals

Gastric Electrical Stimulation (GES) is an FDA approved therapy for gastroparesis with unspecified working mechanisms. One plausible mechanism is that it activates the vagal afferents to engage the brain’s interoceptive network in regulating the stomach. Orientation and location-specific stimulation that targets the vagal-gastric receptors can effectively activate the brainstem. We asked whether and how this type of GES can engage interoceptive regions and modulate their interactions, especially the anterior cingulate (ACC) and insular cortices (IC), the primary visceromotor and viscerosensory processing regions, respectively. Therefore, we evaluated the functional connectivity in the rat brain before, during, and after targeted GES.Purpose

Gastric Electrical Stimulation (GES) is an FDA approved therapy for gastroparesis with unspecified working mechanisms [1]. One plausible mechanism is that GES activates the vagal afferent neurons to engage the brain’s interoceptive network in regulating the stomach. Recent studies have elucidated the locations and types of vagal afferent receptors in the stomach [2]. Orientation and location-specific stimulation that targets the vagal-gastric receptors can effectively activate the brainstem nuclei that receive the ascending signal from the stomach [3]. Extending these prior studies, we further ask whether and how targeted stimulation of vagal-gastric receptors can engage higher-level regions involved in interoception and modulate their patterns of interaction within the brain. Of particular interest are the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and the insular cortex (IC), which have been known as the primary cortical regions for visceromotor and viscerosensory processing, respectively. To address these questions, we evaluated the functional connectivity in the rat brain before, during, and after GES targeted to vagal afferent mechanoreceptors.Methods

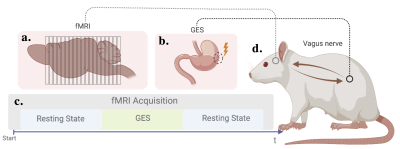

We performed fMRI on a group of anesthetized Sprague Dawley rats (n=4) that were implanted with stainless steel stimulation electrodes (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA). The implantation site was chosen based on previous structural knowledge of the underlying distribution of vagus nerve afferents in the stomach wall [2]. Animals were fasted overnight prior to the experiment. Each animal underwent two fMRI sessions on two separate days in a random order. One session was designed to investigate the short-term effects of GES, it included 50-60 min of GES in between two resting states of the same duration (Figure 1). GES was administered every 30 sec with the following parameters: pulse width= 0.3 ms, current = 1 mA, inter-pulse interval = 0.1 s. The purpose of the other rsfMRI session that was acquired on a separate day was to make sure that the baseline resting state results were consistent across different days. During the imaging session, the animal was anesthetized by continuous subcutaneous infusion of dexmedetomidine (25 μg/(Kg x hour)) and Isoflurane (0.5% mixed with O2) inhalation. fMRI was acquired with a 7T small animal MRI system (Varian) using single-short echo planar imaging (TR=1.2s, TE=18ms, voxel size=0.5x0.5x1 mm3). After preprocessing, we computed the seed-based correlation using two seeds: the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) as the cortical hub for visceromotor processing and the insular cortex (IC) as the cortical hub for viscerosensory processing. Seed-based correlations were thresholded at 0.2. We also computed the correlations between 89 regions of interests (ROIs) presumably involved in interoception. The correlations between ROIs were thresholded at 0.1. Small negative correlations were also discarded. For both seed-based and ROI-level FC, we evaluated the difference in FC 1) between the resting state before GES and the state during GES, and 2) between the resting states before and after GES.Results

Baseline resting state functional connectivity was stable across two different days. GES appeared to enhance the functional connectivity with ACC or IC (Figure 2.a to 2.d) and functional connectivity between the ROIs within the interoceptive network (Figure 2.e & 2.f). The changes in functional connectivity were mostly symmetric between the two hemispheres. GES modulation of functional connectivity persisted even after the stimulation was turned off, although less strongly (Figure 3). Interestingly, the connectivity between NTS and the rest of the cortical regions was also weakened or eliminated after GES administration was terminated (Figure 3.e).Conclusion

Gastric electrical stimulation that targets the vagal mechanoreceptors in the stomach can not only activate vagal afferents and their downstream nuclei (e.g., the nucleus tractus solitarius) but also increase the functional connectivity within the brain’s interoceptive network including regions at brainstem, subcortical, and cortical levels. The increase in functional connectivity not only occurs during the period of stimulation but also persists even after the termination of stimulation. These effects lend support to a potentially effective bioelectric intervention that exerts acute and prolonged regulation of the large-scale network along the brain-stomach neuroaxis. Results reported herein also merit future research to gain further insights into the origins and treatments of gastric disorders.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

[1] H. Soliman and G. Gourcerol, “Gastric Electrical Stimulation: Role and Clinical Impact on Chronic Nausea and Vomiting,” Front. Neurosci., vol. 16, 2022, Accessed: Sep. 25, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnins.2022.909149

[2] T. L. Powley, C. N. Hudson, J. L. McAdams, E. A. Baronowsky, and R. J. Phillips, “Vagal Intramuscular Arrays: The Specialized Mechanoreceptor Arbors That Innervate the Smooth Muscle Layers of the Stomach Examined in the Rat,” J. Comp. Neurol., vol. 524, no. 4, pp. 713–737, Mar. 2016, doi: 10.1002/cne.23892.

[3] Cao, J., Wang, X., Powley, T.L. and Liu, Z., 2021. Gastric neurons in the nucleus tractus solitarius are selective to the orientation of gastric electrical stimulation. Journal of Neural Engineering, 18(5), p.056066.

[4] T. L. Powley, “Brain-gut communication: vagovagal reflexes interconnect the two ‘brains,’” Am. J. Physiol.-Gastrointest. Liver Physiol., vol. 321, no. 5, pp. G576–G587, Nov. 2021, doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00214.2021.

Figures