0464

Longitudinal QSM imaging reveals disrupted subcortical white matter maturation in football vs volleyball college athletes1Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, United States, 2Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Traumatic brain injury, Quantitative Susceptibility mapping

Head impacts in sports may cause long-term brain changes. Here, we assessed quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM) changes over multiple seasons in high-contact American football vs low-contact volleyball college athletes using the multi-echo complex total field inversion (mcTFI) method. We found widespread changes over time (likely developmental) in all athletes, while time-independent sports differences were detected by R2*. mcTFI revealed an altered QSM trajectory in the white matter (total and subcortical) between sports: QSM increased in volleyball athletes but changed minimally in football, likely indicating disrupted subcortical white matter maturation in football. QSM can sensitively detect longitudinal changes in contact sports.Introduction

Head injuries are very common and have devastating health, economic, and societal consequences1. Head impacts from contact sports such as college American football, even without concussion2, may alter athletes’ brains, possibly leading to neurological impairment3, while players largely underestimate risks4. Quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM), a method sensitive to tissue’s magnetic susceptibility, is a promising tool for investigating brain injury5–7. Here, we report longitudinal QSM results on high-contact (football) vs low-contact (volleyball) college athletes over multiple seasons of play.Methods

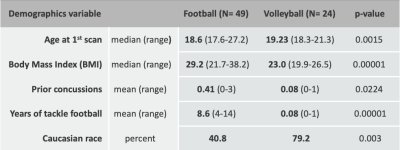

Subjects: We analyzed imaging data from 49 football and 24 volleyball athletes (268 scans with up to 4 years of followup), see Fig. 1. Athletes were scanned at each season’s start, and after their last season of sport participation.Imaging: Using a 3T GE-MR750 scanner with an 8-channel receive head coil, we acquired (1) T1-weighted images (inversion recovery fast spoiled gradient echo) with TR=7.9ms, TE= 3.1ms, NEX=1, 1mm isotropic, and (2) an axial 3D multi-echo gradient echo sequence (ME-GRE), with 8 TEs (5-40ms, 5ms spacing), TR=45ms, FA 15o, BW 62, frequency S/I, flow compensation, 1mm isotropic, matrix 256x218x256, ARC 2x2.

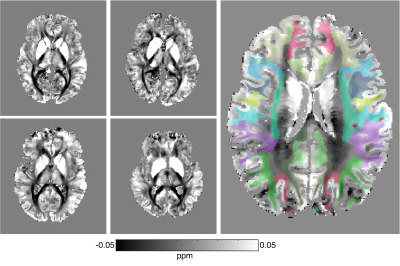

Data processing: T1w images were segmented using the FreeSurfer 5.3 longitudinal pipeline as previously described8. Mean magnitude images from the ME-GRE were registered to T1w images using Freesurfer’s bbregister. The freesurfer segmentation was then transformed to ME-GRE space. QSM and R2* were calculated using the recently-developed multi-echo complex total field inversion (mcTFI) method9, Fig. 2, which provides robust results compared to alternative methods10,11. Images were manually inspected both for quality, segmentation, and coregistration between T1w and ME-GRE. Median mcTFI QSM and R2* values per Freesurfer regions were computed, and a linear-mixed-effects (LME) model in Stata-15 was used to study longitudinal changes after combining regions into larger compartments (e.g. combining first across hemispheres, then across regions within a lobe of the brain, etc. as in 8). Sport, time, and their interaction were considered fixed effects, while subjects were random effects.

Results

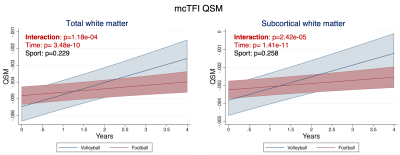

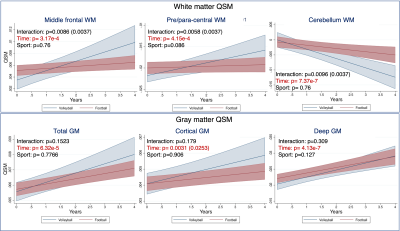

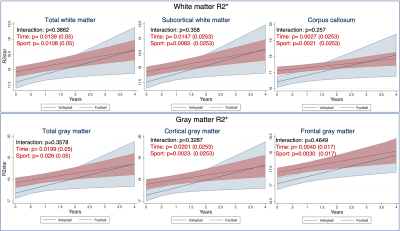

Altered trajectories in football vs volleyball players white matter revealed by QSM: The LME model revealed significantly different trajectories of QSM values in the white matter of football vs volleyball athletes over time, Fig. 3: the total white matter QSM values of volleyball players increase over time, whereas the ones of football players are almost stable, increasing with very small slope, Fig. 3A. This effect seems to be mainly driven by the QSM changes in subcortical white matter, Fig. 3B. Similar longitudinal trends (volleyball athlete values changing more than football ones), yet not statistically significantly different between sports, were identified in the mcTFI QSM values in other white and gray matter regions too, cf Fig. 4.Longitudinal differences in white and gray matter over time in both sports: QSM values in total white and gray matter of both football and volleyball players seemed to change significantly over time, Figs. 3,4. This effect was also present in various white and gray matter subregions, including subcortical white matter Fig. 3B, middle frontal, pre- and para-central and cerebellum white matter, Fig. 4A, and both cortical and deep gray matter, Fig. 4B. Similar differences over time (but in fewer regions) were also captured by R2*, Fig. 5.

Time-independent changes in football vs volleyball athlete brains detected by R2*: Apart from the R2* time effect, there was also a significant football vs volleyball difference in white and gray matter R2* values independent of time, Fig. 5. Specifically, the football players had higher R2* values in total white and gray matter, and multiple subregions (subcortical white matter and corpus callosum, total cortical and frontal gray matter), with the effect being stronger in white than in gray matter. Volleyball vs football R2* trajectories over time were not significantly different.

Discussion

Few previous studies investigated QSM changes in athletes. Gong et al. reported no QSM changes after a high-school football season12, and Weber et al. found no concussion-related QSM changes in hockey players. Koch et al. reported white matter QSM changes in high-school football athletes post-concussion13, and Brett et al. found that years of exposure predicted white matter QSM changes in high-school and college football and soccer athletes14.Using our LME model across white and gray matter, we detected differential QSM (but not R2*) trajectories in the white matter (especially subcortical) of football vs volleyball athletes, with QSM values increasing considerably in volleyball but very little in football. Given that subcortical connections undergo late myelination15, which requires a lot of iron16, there may be a disrupted subcortical myelination in high-contact football compared to low-contact volleyball athletes. Such hypothesis is also supported by our previously reported slower cortical thinning8 and microstructural white matter trajectories17 in football vs volleyball athletes.

We also found sport (football vs volleyball) R2* differences in white and gray matter, but these are mostly due to baseline differences, and it is unclear if they are caused by development, prior impacts, or other reasons. Increases in QSM and R2* values over time in white and gray matter in both sports possibly reflect normal developmental changes in this age range18–22, consistent with our hypothesis.

Conclusion

QSM can detect longitudinal changes in high- vs low-contact sports that could be related to abnormal white-matter development.Acknowledgements

Research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) award number R01AG061120-01.References

1. Neurology, T. L. Traumatic brain injury: time to end the silence. Lancet Neurol. 9, 331 (2010).

2. Bazarian, J. J., Zhu, T., et al. Persistent, long-term cerebral white matter changes after sports-related repetitive head impacts. PLoS One 9, (2014).

3. Phelps, A., Alosco, M. L., et al. Association of Playing College American Football With Long-term Health Outcomes and Mortality. JAMA Netw. Open 5, e228775–e228775 (2022).

4. Baugh, C. M., Kroshus, E., Meehan III, W. P., McGuire, T. G. & Hatfield, L. A. Accuracy of US College Football Players’ Estimates of Their Risk of Concussion or Injury. JAMA Netw. Open 3, e2031509–e2031509 (2020).

5. Beauchamp, M. H., Beare, R., et al. Susceptibility weighted imaging and its relationship to outcome after pediatric traumatic brain injury. Cortex. 49, 591–598 (2013).

6. Daglas, M. & Adlard, P. A. The Involvement of Iron in Traumatic Brain Injury and Neurodegenerative Disease. Front. Neurosci. 12, 981 (2018).

7. Gozt, A., Hellewell, S., Ward, P. G. D., Bynevelt, M. & Fitzgerald, M. Emerging Applications for Quantitative Susceptibility Mapping in the Detection of Traumatic Brain Injury Pathology. Neuroscience 467, 218–236 (2021).

8. Mills, B. D., Goubran, M., et al. Longitudinal alteration of cortical thickness and volume in high-impact sports. Neuroimage 217, 116864 (2020).

9. Wen, Y., Spincemaille, P., et al. Multiecho complex total field inversion method (mcTFI) for improved signal modeling in quantitative susceptibility mapping. Magn. Reson. Med. 86, 2165–2178 (2021).

10. Committee, Q. S. M. C. 2. . O., Bilgic, B., et al. QSM reconstruction challenge 2.0: Design and report of results. Magn. Reson. Med. 86, 1241–1255 (2021).11. Champagne, A. A., Wen, Y., et al. Quantitative Susceptibility Mapping for Staging Acute Cerebral Hemorrhages: Comparing the Conventional and Multiecho Complex Total Field Inversion magnetic resonance imaging MR Methods. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 54, 1843–1854 (2021).

12. Gong, N.-J., Kuzminski, S., et al. Microstructural alterations of cortical and deep gray matter over a season of high school football revealed by diffusion kurtosis imaging. Neurobiol. Dis. 119, 79–87 (2018).

13. Koch, K. M., Meier, T. B., et al. Quantitative Susceptibility Mapping after Sports-Related Concussion. AJNR. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 39, 1215–1221 (2018).

14. Brett, B. L., Koch, K. M., et al. Association of Head Impact Exposure with White Matter Macrostructure and Microstructure Metrics. J. Neurotrauma 38, 474–484 (2021).

15. Arshad, M., Stanley, J. A. & Raz, N. Adult age differences in subcortical myelin content are consistent with protracted myelination and unrelated to diffusion tensor imaging indices. Neuroimage 143, 26–39 (2016).

16. Cheli, V. T., Correale, J., Paez, P. M. & Pasquini, J. M. Iron Metabolism in Oligodendrocytes and Astrocytes, Implications for Myelination and Remyelination. ASN Neuro 12, 1759091420962681 (2020).

17. Goubran, M., Mills, B. D., et al. Microstructural alterations in tract development in college football: a longitudinal diffusion MRI study. bioRxiv 2022.04.01.486632 (2022) doi:10.1101/2022.04.01.486632.

18. Khattar, N., Triebswetter, C., et al. Investigation of the association between cerebral iron content and myelin content in normative aging using quantitative magnetic resonance neuroimaging. Neuroimage 239, 118267 (2021).

19. Larsen, B., Bourque, J., et al. Longitudinal Development of Brain Iron Is Linked to Cognition in Youth. J. Neurosci. 40, 1810 LP – 1818 (2020).

20. Keuken, M. C., Bazin, P.-L., et al. Effects of aging on T1, T2*, and QSM MRI values in the subcortex. Brain Struct. Funct. 222, 2487–2505 (2017).

21. Li, Y., Sethi, S. K., et al. Iron Content in Deep Gray Matter as a Function of Age Using Quantitative Susceptibility Mapping: A Multicenter Study . Frontiers in Neuroscience vol. 14 (2021).

22. Peterson, E. T., Kwon, D., et al. Distribution of brain iron accrual in adolescence: Evidence from cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis. Hum. Brain Mapp. 40, 1480–1495 (2019).

23. Lee, S. & Lee, D. K. What is the proper way to apply the multiple comparison test? Korean J. Anesthesiol. 71, 353–360 (2018).

Figures