0462

Quantitative Susceptibility Mapping in Patients with Persistent-Post Concussion Symptoms1Department of Radiology, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada, 2Hotchkiss Brain Institute, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada, 3Alberta Children's Hospital Research Institute, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada, 4Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada, 5Department of Clinical Neuroscience, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada, 6Calgary Image Processing and Analysis Centre, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada

Synopsis

Keywords: Traumatic brain injury, Quantitative Susceptibility mapping, "Persistent Post-Concussion Symptoms"

Twenty percent of people experience symptoms months to years following a concussion, known as persistent post concussive symptoms (PPCS). We used quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM) to measure tissue susceptibility in white matter tracts of patients with PPCS. We provide preliminary evidence for alterations in white matter susceptibility in patients with PPCS and show that susceptibility levels are correlated with symptom severity. We hypothesise altered susceptibility is related to gliosis, resulting in sustained inflammation. Further, this study demonstrates the potential application of QSM to provide novel information on the pathophysiology of PPCS.Introduction

Concussion is the most common form of brain injury. Though most people recover within weeks, roughly 20% of people still have symptoms months to years afterward, known as persistent post-concussion symptoms (PPCS). Symptoms include headache, dizziness, nausea, memory deficits, difficulty concentrating, sleep difficulties and mood disruption.1 Symptoms can be debilitating, severely impacting quality of life. Treatment options are limited, in part due to a lack of understanding of PPCS pathophysiology. Physiological changes following brain injury are often not identified on conventional neuroimaging, however advanced neuroimaging methods can reveal subtle alterations not previously detected.Quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM) can detect changes in tissue susceptibility following pathological processes associated with concussion, such as demyelination, accumulation of iron and calcium, and gliosis.2 Using QSM, previous studies have shown that, compared to controls, patients 8 days post-concussion have higher global white matter susceptibility3,4, as well as higher susceptibility in multiple white matter tracts.3 However, there have been no studies investigating tissue susceptibility differences in patients with PPCS. The aim of this study is to compare QSM measured white matter susceptibility in patients with PPCS and healthy controls.

Methods

Thirty-four patients with PPCS (mean age=43.3±10.9 y, 25 female, mean time since injury=26.3±15.2 months, 5 sport related) and 42 healthy controls with no lifetime history of brain injury (mean age=43.2±10.8, 26 female) were included. Patients completed the following symptom questionnaires: Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS), Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), Rivermead Post-Concussion Symptoms Questionnaire (RPQ), Post-Concussion Syndrome Checklist (PCSC), Headache Impact Test-6 (HIT-6) and the Dizziness Handicap Inventory (DHI).QSM data were obtained on a 3T MR scanner (General Electric 750w) using a 32-channel head coil. A T1-weighted structural image was acquired using a BRAVO sequence (TR/TE/TI=7.30/2.70/600 ms, matrix size=256x256, FOV=252x278 mm2, voxel size=0.94 mm2, slice thickness=1 mm, flip angle=10◦). QSM data were acquired using the following parameters: TR=56.7 ms; TE=4.5 – 52.2 ms, 10 echos with echo spacing 5.3 ms, matrix size=256x256, FOV=240 mm, voxel size=0.94 mm2, 1.9 mm slice thickness.

QSM data were processed using a customised pipeline from the Calgary Image Processing and Analysis Centre (CIPAC)5 which includes: brain extraction on the magnitude and phase images using FSL BET,6 phase unwrapping using BESTPATH,7 weighted least squares calculation of the field from the phase, background field removal with RESHARP,8 and dipole inversion with TV regularization.9 QSM data were registered to MNI space using FSL FLIRT.10

White matter masks were generated using the Harvard-Oxford11 and Johns Hopkins12 atlases for the following regions: global white matter, anterior thalamic radiation, cingulum, forceps minor, inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus, inferior longitudinal fasciculus, superior longitudinal fasciculus, superior longitudinal fasciculus (temporal region) and the corpus callosum (separated into the body, genus and splenium). Mean susceptibility values were computed from each region of interest for each subject. ANCOVAs were used to compare susceptibility for each region between groups while controlling for age and sex. Partial correlations were used to assess the relationship between susceptibility in each region and symptom scores while also controlling for age and sex.

Results

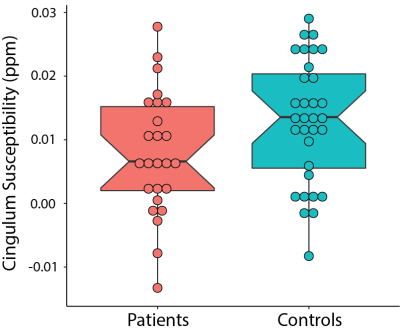

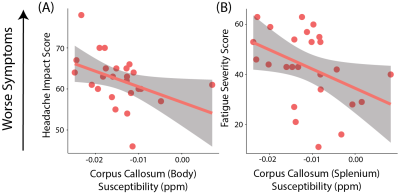

Patients with PPCS had lower susceptibility in the cingulum compared to healthy controls, however this did not reach statistical significance (F(1,61)=3.63, p=0.06, η2=0.06; Figure 1).Lower susceptibility values in the corpus callosum body of patients with PPCS were associated with higher scores on the HIT-6 (r(22)=-0.44, p=0.03). Lower susceptibility values in the corpus callosum splenium were associated with higher scores on the FSS (r(22)=-0.40, p=0.05; Figure 2).

Discussion

Using QSM we show patients with PPCS had altered tissue susceptibility levels in the cingulum compared to healthy controls, and that lower susceptibility levels in the corpus callosum were associated with higher symptom burden.Previous research found higher susceptibility levels in patients 8 days post-concussion compared to uninjured controls in multiple white matter tracts. This increase was attributed to edema. The majority of these differences had resolved by 6 months post-concussion, except for the right cingulum, which still showed a significant difference (however the direction was not specified).3 Here we show patients with PPCS had lower susceptibility than healthy controls in this region, though this did not reach statistical significance. In line with the direction of this difference, we also show lower susceptibility in areas of the corpus callosum were associated with worse symptoms, specifically fatigue and functional impact of headache. This finding is also in line with animal models of brain injury. Chary et al showed a decrease in corpus callosum susceptibility 6 months following injury. In the same area they found increased cell density, attributed to gliosis.2 Damage to the corpus callosum is one of the most reported abnormalities following brain injury.13 Gliosis can help regulate the inflammatory response but can also release free radicals and proinflammatory cytokines. A sustained inflammatory state is a significant contributor to secondary damage and neurological impairments.14 It is possible that patients with more severe symptoms are experiencing higher levels of sustained inflammation.

In conclusion we provide evidence for alterations in white matter susceptibility in patients with PPCS. We show that susceptibility levels are correlated with symptom severity and hypothesize this may be due to sustained inflammation. Further, this study demonstrates the potential for application of QSM to provide novel information on PPCS pathophysiology.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a New Frontiers in Research Fund Exploration Grant, Foundations of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, an Hotchkiss Brain Institute PFUND Award and a Canada Foundation for Innovation John R. Evans Leaders Fund award. ADH holds a Canada Research Chair in Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy in Brain Injury.References

[1] A. Hadanny and S. Efrati, “Treatment of persistent post-concussion syndrome due to mild traumatic brain injury: current status and future directions,” Expert Rev. Neurother., vol. 16, no. 8, pp. 875–887, 2016, doi: 10.1080/14737175.2016.1205487.

[2] K. Chary et al., “Quantitative susceptibility mapping of the rat brain after traumatic brain injury,” NMR Biomed., vol. 34, no. 2, pp. 1–15, 2021, doi: 10.1002/nbm.4438.

[3] K. M. Koch, T. B. Meier, R. Karr, A. S. Nencka, L. T. Muftuler, and M. McCrea, “Quantitative susceptibility mapping after sports-related concussion,” Am. J. Neuroradiol., vol. 39, no. 7, pp. 1215–1221, 2018, doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A5692.

[4] K. M. Koch, A. S. Nencka, B. Swearingen, A. Bauer, T. B. Meier, and M. McCrea, “Acute Post-Concussive Assessments of Brain Tissue Magnetism Using Magnetic Resonance Imaging,” J. Neurotrauma, vol. 38, no. 7, pp. 848–857, 2021, doi: 10.1089/neu.2020.7322.

[5] S. M, G. DG, M. DA, M. CR, L. ML, and F. R., “Cerebra-QSM: An Application for Exploring Quantitative Susceptibility Mapping Algorithms,” in International Society for Magnetic Resonanace in Medicine 25th Annual Meeting, 2017, p. 3822.

[6] S. M. Smith, “Fast robust automated brain extraction,” Hum. Brain Mapp., vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 143–155, 2002.

[7] H. S. Abdul-Rahman, M. A. Gdeisat, D. R. Burton, M. J. Lalor, F. Lilley, and C. J. Moore, “Fast and robust three-dimensional best path phase unwrapping algorithm,” Appl. Opt., vol. 46, no. 26, p. 6623, Sep. 2007, doi: 10.1364/AO.46.006623.

[8] H. Sun and A. H. Wilman, “Background field removal using spherical mean value filtering and Tikhonov regularization,” Magn. Reson. Med., vol. 71, no. 3, pp. 1151–1157, 2014, doi: 10.1002/mrm.24765.

[9] B. Bilgic et al., “Fast quantitative susceptibility mapping with L1-regularization and automatic parameter selection,” Magn. Reson. Med., vol. 72, no. 5, pp. 1444–1459, 2014, doi: 10.1002/mrm.25029.

[10] M. Jenkinson, P. R. Bannister, J. M. Brady, and S. M. Smith, “Improved Optimisation for the Robust and Accurate Linear Registration and Motion Correction of Brain Images,” Neuroimage, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 825–841, 2002.

[11] R. S. Desikan et al., “An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest,” Neuroimage, vol. 31, no. 3, pp. 968–980, Jul. 2006, doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.021.

[12] K. Hua et al., “Tract probability maps in stereotaxic spaces: Analyses of white matter anatomy and tract-specific quantification,” Neuroimage, vol. 39, no. 1, pp. 336–347, Jan. 2008, doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.07.053.

[13] M. Gumus, A. Santos, and M. C. Tartaglia, “Diffusion and functional MRI findings and their relationship to behaviour in postconcussion syndrome: a scoping review,” J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry, vol. 92, no. 12, pp. 1259–1270, 2021, doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2021-326604.

[14] B. Fehily and M. Fitzgerald, “Repeated mild traumatic brain injury: Potential mechanisms of damage,” Cell Transplant., vol. 26, no. 7, pp. 1131–1155, 2017, doi: 10.1177/0963689717714092.

Figures