0460

MRE-based assessment of impairment of mechanical isolation at the skull-brain interface resulting from sports-related head impact exposure1Radiology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, United States, 2Physiology and Biomedical Engineering, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Traumatic brain injury, Elastography, Repeated head impact

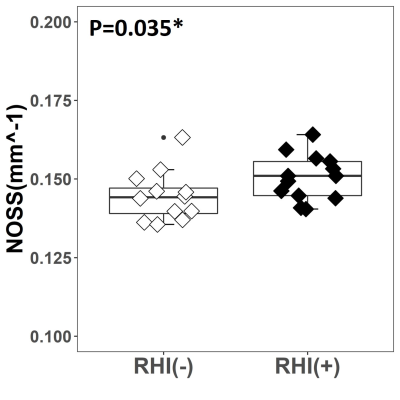

Increasing recognition of the effect of repeated head impacts (RHI) in leading to neurologic impairment and higher risk of subsequent traumatic head injury, has motivated for developing technology to assess the status of the mechanism of mechanical isolation provided by the structures within the skull-brain interface, known as the pia-arachnoid complex (PAC). To evaluate the RHI-induced PAC alternations, we compared MR elastography-based measures (rotational transmission ratio [Rtr] and cortical normalized octahedral shear strain [NOSS]) between healthy and sports-related RHI subjects. Significantly higher Rtr and cortical NOSS were found among RHI individuals, showing their potential in assessing the effect of RHI.Introduction

Subconcussive repeated head impact (RHI) is a public health issue[1]. Increasing evidence has shown an association between RHI exposure and a higher risk of neurological disorders and subsequent traumatic brain injury[2]. The skull-brain interface, known as the pia-arachnoid complex (PAC), protects the brain from external impacts by dampening and isolating external motions[3]. As the brain’s protective membrane system, it is expected to be vulnerable to disruption from head impacts. The development of technology to assess the status of the mechanism of mechanical isolation provided by the skull-brain interface would help track vulnerable populations and avoid future damage. Our previous studies developed two MR elastography (MRE)-based parameters, rotational transmission ratio (Rtr)[4] and cortical normalized octahedral shear strain (NOSS)[5], to measure the mechanical dampening and isolation capability of the skull-brain interface noninvasively and quantitatively. Under vibration induced by MRE, Rtr quantifies how much rotational motion is transmitted from the skull to the brain, and cortical NOSS measures the cortical surface deformation normalized to account for impact strength. In this study, we aimed to measure and visualize the RHI-associated Rtr and cortical NOSS changes. We hypothesized that RHI exposure would result in impairment of mechanical isolation at the skull-brain interface.Methods

With IRB approval and written informed consent, 25 volunteers were included in this study. The RHI(+) group had 13 volunteers (age: 16-23 years, 19.2 ± 2.1 years, male) with a self-reported history of contact-sports participation and received MRE scans within three years after ending participation, and the RHI(-) group had 12 age/sex-matched healthy controls (age: 18-23 years, 20.5 ± 2.0 years, male) with no history of any contact-sports participation. All brain MRE exams were performed on a recently developed high-performance compact 3T MRI scanner[6]. 60 Hz harmonic vibrations were introduced into the brain through a customized pneumatic driver as previously described[7]. A dual-sensitivity and dual-motion encoding (DSDM) MRE pulse sequence was used to measure the 3D skull and brain motions[7]. The displacement data were converted from the MRI phase signals for Rtr and NOSS computation. The skull and brain rotational motions were obtained by fitting the skull and brain displacement vectors separately to a rigid body model[7]. The 3D motion of each voxel was then projected into a high-resolution T1W image for animated visualization of the relative skull and brain rotation during the MRE vibration. The Rtr (defined as the brain-to-skull amplitude ratio of the rotation) was calculated for each subject. For NOSS calculation, the octahedral shear strain was computed by a neural network-based algorithm[8], then normalized to the wave motion amplitude[9]. Cortical NOSS maps were extracted and displayed by FreeSurfer and customized MATLAB scripts[5, 10]. The Desikan-Killiany Atlas[11] was employed for regional analysis. The Mann-Whitney U test was utilized to measure the differences between the RHI(-) and RHI(+) groups on Rtr and cortical NOSS (p < 0.05 was defined as statistically significant).Results and Discussion

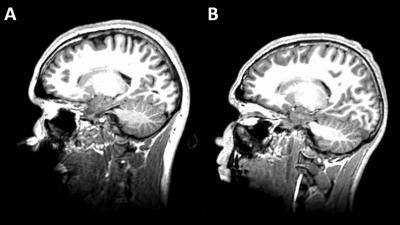

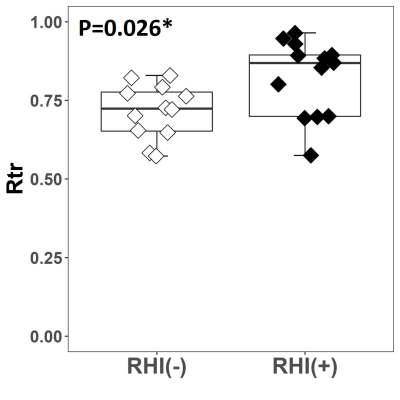

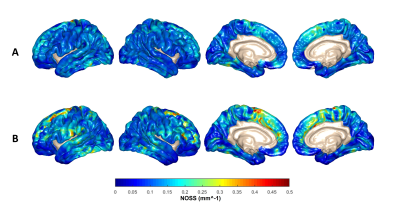

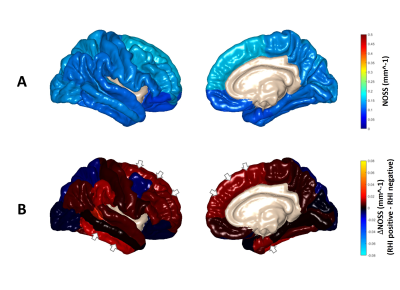

Figure 1 shows two representative cases of amplified (x1000 times) skull and brain rotational motions from two age/sex-matched RHI(+) and RHI(-) volunteers. Although the RHI(-) volunteer had larger vibrations as indicated by the larger skull motion, the amplitude of brain rotation is visually lower than in the RHI(+) volunteer. We found significantly elevated Rtr in the RHI(+) group versus RHI(-) controls (Figure 2). Higher Rtr indicates that more rigid body rotation was directly transmitted to the brain, which may suggest a decreased mechanical dampening capability of the skull-brain interface. Figure 3 shows representative cortical NOSS distributions from two age/sex-matched volunteers. Elevated NOSS values were found in the RHI(+) volunteer in the frontal and temporal lobes, which are vulnerable to head trauma. Regional cortical NOSS changes associated with the RHI group are displayed in Figure 4. Consistently, the RHI(+) group shows increasing NOSS values in the frontal and temporal lobes, especially in the superior frontal and inferior temporal. Significant NOSS increases were found in the RHI(+) group in the superior frontal region (Figure 5), while increases were found in the inferior temporal region but did not reach significance. The high NOSS observed in the RHI(+) group indicates that some localized brain surfaces may deform easily, presumably due to the degraded mechanical isolation capability of the skull-brain interface locally. Of note, in this study, we only included participants with less than 3 years since ending participation. Given the complexity of RHI injury mechanisms from various perspectives, including sports type, age at the first exposure, type and magnitude of exposure, career duration, and other factors, a future study with a larger spectrum of participants is warranted to validate our findings.Conclusion

This study provides preliminary evidence that MRE-based characterization of the isolation capacity of the protective structures at the skull-brain interface (measured as Rtr and cortical NOSS) has the potential as biomarkers for noninvasively assessing the functional status of the skull-brain interface and for aiding clinicians in identifying individuals who have sustained RHI-induced injury.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the NIH (R01EB001981, R01NS113760, R01EB027064, and U01EB024450).References

1. Montenigro, P.H., et al., Cumulative head impact exposure predicts later-life depression, apathy, executive dysfunction, and cognitive impairment in former high school and college football players. Journal of neurotrauma, 2017. 34(2): p. 328-340.

2. Control, C.f.D. and Prevention. Report to congress on traumatic brain injury in the United States: epidemiology and rehabilitation. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control 2015 [cited 2; 1-72]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/traumaticbraininjury/pubs/congress_epi_rehab.html.

3. Haines, D.E., Chapter 7 - The Meninges, in Fundamental Neuroscience for Basic and Clinical Applications (Fifth Edition), D.E. Haines and G.A. Mihailoff, Editors. 2018, Elsevier. p. 107-121.e1.

4. Yin, Z., et al., MR Elastography (MRE)-assessed skull-brain coupling is affected by sports-related repetitive head impacts (RHI), in 2019 International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine Annual Meeting. 2019: Montreal, Canada.

5. Shan, X., et al., MRI-based cortical shear strain measurement in healthy volunteers: repeatability study and its implications for sub-concussive trauma, in 2022 International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine Annual Meeting. 2022: London, UK.

6. Weavers, P.T., et al., Compact three‐tesla magnetic resonance imager with high‐performance gradients passes ACR image quality and acoustic noise tests. Medical physics, 2016. 43(3): p. 1259-1264.

7. Yin, Z., et al., In vivo Characterization of 3D Skull and Brain Motion During Dynamic Head Vibration Using Magnetic Resonance Elastography. Magn Reson Med, 2018. 80(6): p. 2573-85.

8. Murphy, M.C., et al., Artificial neural networks for numerical differentiation with application to magnetic resonance elastography, in 2020 International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine Annual Meeting. 2020: Virtual.

9. Yin, Z., et al., Slip interface imaging based on MR‐elastography preoperatively predicts meningioma–brain adhesion. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 2017. 46(4): p. 1007-1016.

10. Fischl, B., FreeSurfer. Neuroimage, 2012. 62(2): p. 774-781.

11. Desikan, R.S., et al., An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. Neuroimage, 2006. 31(3): p. 968-980.

Figures