0456

Association between brain metabolites and head impact exposure measured with MRS in a cohort of high school American football athletes1Department of Biomedical Engineering, Georgia Institute of Technology and Emory University, Atlanta, GA, United States, 2Imaging Research Center, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH, United States, 3Department of Neuroscience, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA, United States, 4Emory Sports Performance And Research Center (SPARC), Flowery Branch, GA, United States, 5Emory Sports Medicine Center, Atlanta, GA, United States, 6Department of Orthopedics, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, United States, 7Department of Radiology, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, OH, United States, 8Neuroscience Graduate Program, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, OH, United States, 9Department of Kinesiology, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Greensboro, NC, United States, 10The Micheli Center for Sports Injury Prevention, Waltham, MA, United States, 11Department of Radiology and Imaging Sciences, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Traumatic brain injury, Spectroscopy

Diagnosis and prognosis of sports-related concussion is challenging. In this prospective controlled clinical trial of 215 high school American football athletes, we evaluated relationships between brain metabolite and head impacts as a function of concussion diagnosis and wearing a jugular vein compression (JVC) collar. Changes in total choline between pre- and post-season, measured with MR spectroscopy, were positively correlated with mean g-force thresholds above 80g in athletes diagnosed with a concussion, suggesting choline may be a key metric of injury. Metabolite alterations were minimally affected by the JVC collar and only at mean g-force thresholds of 100, 110 and 120g.Introduction

Sports-related concussion, or mild traumatic brain injury, occurs frequently in athletes involved in contact sports including American football.1 Heterogeneous clinical presentation leads to challenges in diagnosis and prognosis. Furthermore, repeated impacts, even in the absence of diagnosed concussion, is a growing concern for football athletes.2 Magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) has been used previously to assess neurochemical alterations in cross-sectional studies3 and sub-concussive impacts,4 but the effect of concussion diagnosis on the relationships between brain metabolites and head impacts are unexplored. The primary goal of this study was to quantify alterations in brain metabolites, as well as the relationships between brain metabolites and head impacts, as a function of concussion diagnosis, during a single season of American football in a cohort of high school athletes. The effect of wearing a jugular vein compression (JVC) collar5 was also evaluated.Methods

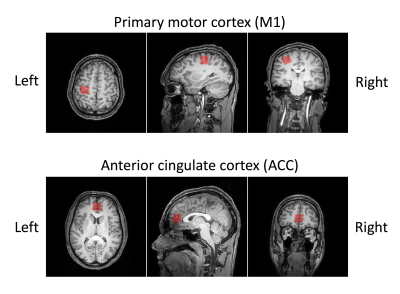

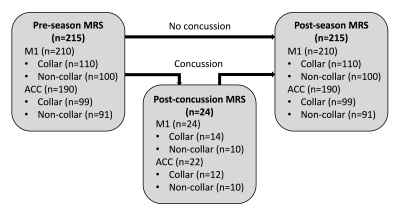

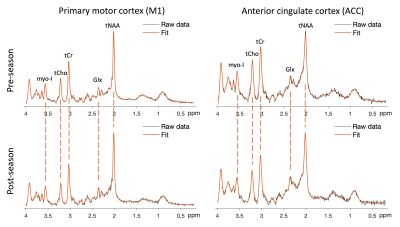

This study was conducted as part of a larger prospective controlled clinical trial, approved by the local institutional review board. MR data were acquired in 215 male participants (16±1 years old) across 7 schools at pre-season, post-season, and after a diagnosed concussion (post-concussion). All MR data was collected using three Phillips 3 T MR scanners (Achieva, Ingenia, and Ingenia Elition) with a 32-channel phased array head coil. Single-voxel MRS data were acquired in the left primary motor cortex (M1) and rostral anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) (Figure 1) using a point-resolved spectroscopy (PRESS) sequence (TR/TE=2000/30ms, flip angle=90°, averages=96, bandwidth=2000 Hz, complex data points=1024, voxel size=2×2×2cm3). A T1-weighted magnetization-prepared rapid gradient echo (MPRAGE) image (TR/TI/TE = 8.1/1070/3.7ms, FOV=256×256mm2, 180 slices, voxel size=1×1×1mm3) was acquired and used to position MRS voxels. Spectra were analyzed using LCModel.6 Metabolites, including total N-acetylaspartate + N-acetylaspartate glutamate (tNAA), total glycerophosphocholine + phosphocholine (tCho), myo-inositol (myo-I), and glutamine + glutamate (Glx), relative to total creatine + phosphocreatine (tCr) were used in analysis. The normalized change in metabolite/tCr for all 4 metabolites was calculated as (post-season – pre-season)/pre-season. Head impacts were quantified using an accelerometer placed below the participant’s left mastoid. Mean g-force (total g-force/number of impacts) was calculated for thresholds between 20g and 150g in 10g intervals, where the threshold indicates all impacts above the noted g-force.Differences in metabolite/tCr ratios between pre-season, post-concussion, and post-season were assessed using Friedman’s tests (concussion group) and between pre- and post-season using Wilcoxon signed-rank tests (non-concussion group). Differences in the normalized change in metabolite/tCr between concussion and JVC collar groups were calculated using Mann-Whitney U tests. Linear regressions with interaction effects were used to evaluate the relationships between normalized change in metabolite/tCr (response) and mean g-force (predictor) with concussion and JVC collar as covariates. Post-hoc regressions were performed for significant interaction effects. Significance was determined at p≤.05 and corrected for the false discovery rate for group-wise comparisons.

Results

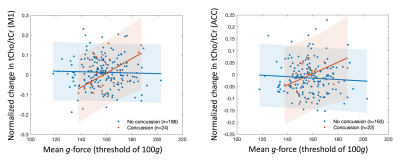

Of 215 participants, 24 were diagnosed with a concussion (Figure 2). Sample MRS spectra are shown in Figure 3. No differences were observed between pre-season, post-concussion, and post-season (concussion group) for any metabolite. In the non-concussion group, myo-I/tCr in M1 and tCho/tCr in the ACC were significantly lower and Glx/tCr in the ACC was significantly higher post-season compared to pre-season. No group-wise differences as a function of concussion diagnosis or JVC collar were observed. The relationships between normalized change in tCho/tCr and mean g-force for thresholds between 80g and 140g varied significantly as a function of concussion diagnosis in M1 (Figure 4, left) and between 80g and 140g, excluding 90g, in the ACC (Figure 4, right). Normalized change in tCho/tCr in M1 was positively and significantly correlated with mean g-force at thresholds of 100 and 110g in the concussion group in post-hoc analysis. The relationship between normalized change in Glx/tCr in the ACC and mean g-force at threshold of 60g significantly varied as a function of concussion diagnosis. Myo-I/tCr in the ACC and mean g-force for thresholds of 100, 110, and 120g significantly varied as a function of JVC collar wear.Discussion

Here, we report the largest longitudinal study to date examining the relationship between brain metabolite alterations measured with MRS and head impacts in high school football athletes. The association between normalized change in tCho/tCr and mean g-force were observed only in the concussion group, indicating tCho may be an important marker of head impacts. Similarly, a prior study observed an association between increases in tCho/tCr from pre- to mid-season and higher mean g-force.4 In contrast to prior studies of concussion in adults,3 we did not observe significant alterations in tNAA/tCr, potentially due to MRS voxels primarily composed of grey matter and age-related differences in tNAA concentration. The effect of JVC collar on brain metabolites was limited in the current cohort.Conclusions

Alterations in brain metabolites pre- and post-season were observed in a cohort of high school athletes. Increased tCho/tCr was positively associated with mean head impacts for thresholds above 80g, suggesting tCho may be a key indicator for concussion-related brain alterations in athletes receiving repetitive impacts of high magnitude. Current work is extending these results to examine the relationships between cognition and motor skills with neurochemical alterations measured with MRS.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Rosenthal JA, Foraker RE, Collins CL, Comstock RD. National high school athlete concussion rates from 2005-2006 to 2011-2012. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(7):1710-1715.

2. Talavage TM, Nauman EA, Breedlove EL, Dye AE, et al. Functionally-detected cognitive impairment in high school football players without clinically-diagnosed concussion. J Neurotrauma. 2014;31(4):327-338.

3. Joyce JM, La PL, Walker R, Harris A. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy of traumatic brain injury and subconcussive hits: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurotrauma. doi: 10.1089/neu.2022.0125.

4. Bari S, Svaldi DO, Jang I, Shenk TE, et al. Dependence on subconcussive impacts of brain metabolism in collision sport athletes: an MR spectroscopic study. Brain Imaging Behav. 2019;13(3):735-749.

5. Diekfuss JA, Yuan W, Barber Foss KD, Dudley JA, et al. The effects of internal jugular vein compression for modulating and preserving white matter following a season of American tackle football: a prospective longitudinal evaluation of differential head impact exposure. J Neurosci Res. 2021;99(2):423-445.

6. Provencher SW. Estimation of metabolite concentrations from localized in vivo proton NMR spectra. Magn Reson Med. 1993;30(6):672-679.

Figures