0450

Cotyledon-Specific Flow Evaluation of Rhesus Macaque Placental Injury using Ferumoxytol Dynamic Contrast Enhanced MRI1Medical Physics, University of Wisconsin - Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 2Wisconsin National Primate Research Center, University of Wisconsin - Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 3Comparative Biosciences, University of Wisconsin - Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 4Obstetrics & Gynecology, University of Wisconsin - Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 5Radiology, University of Wisconsin - Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 6Biomedical Engineering, University of Wisconsin - Madison, Madison, WI, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Placenta, DSC & DCE Perfusion

Placental blood flow is a marker that reflects the health of the utero-placental vasculature. Dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) MRI is more robust than arterial spin labeling and can be utilized in animal models to provide cotyledon-specific blood flow and blood volume measurements in vivo throughout gestation. This study investigated the distribution of blood flow to the placental at a cotyledon level in pregnant rhesus monkeys before and following the injection of Tisseel (a fibrin sealant) and MCP1 (an inflammatory response inducer) to assess the predictabilities of flow for placental injury.Introduction

Abnormal maternal placental vasculature and associated conditions such as local malperfusion can lead to gestational complications1–3. Dynamic contrast enhanced (DCE) MRI is a promising tool to assess placental perfusion and blood flow in-vivo throughout gestation. Recent studies have shown promising results in animal studies using DCE-MRI to identify functional units in the placenta, or cotyledons, which facilitate nutrient and oxygen exchange between the mother and the fetus, and quantify their number, volumes, and flow3–5. However, few studies have reported cotyledon-specific flow values in the presence of placental abnormalities. Here, we report initial results for DCE analysis of two novel rhesus macaque models designed to induce placental injuries. Model 1 used macrophage chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP1), a central effector of inflammatory responses across diverse physiological systems, to induce placental inflammation.6 Model 2 used Tisseel (Baxter Healthcare Corp), an FDA-approved fibrin sealant used surgically to control bleeding, to generate blood clots in the placenta to mimic local placental infarcts.Methods

Subjects: Nine rhesus macaques were imaged at three gestational timepoints (GTPs) of ~100, ~115, and ~145 days. One day after the first MRI session, n=3 monkeys were injected with 0.5ml Tisseel, n=3 with 100ug MCP1, and n=3 with saline as controls. All injections were conducted by an experienced ObGyn clinician under ultrasound guidance and targeted to occur in the intervillous space of the anterior lobe of the placenta. The fetuses were delivered via cesarean section at around day 155, and the placentas were retained for histopathological analysis by a pathologist.Imaging: All scans were performed on a 3.0 T system (Discovery MR750, GE Healthcare) with a 32-channel phased array coil. The subjects were sedated with isoflurane and imaged in right-lateral position. A series of DCE data sets were acquired during ferumoxytol (4mg/kg) infusion, using a respiratory-gated, T1-weighted spoiled gradient echo sequence (DISCO, TR=4.8ms, TE=1.8ms, spatial resolution=0.86×0.86×1.00mm3, temporal resolution = 5.488s, number of timeframes = 40).

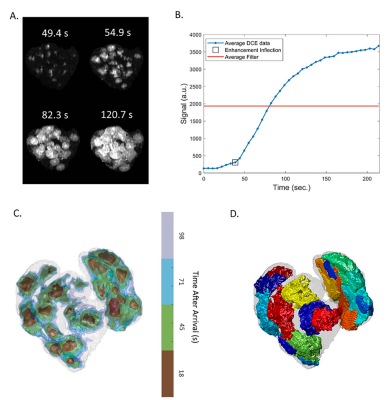

Processing: Semi-manual segmentation (ITK-SNAP7) was performed using the last timepoint of the DCE imaging sequence. Each voxel was fitted to a sigmoid arrival model, and the inflection point of inflow enhancement was used to form contrast arrival maps4. Subsequently, a watershed algorithm was used to determine the boundary of each perfusion domain (ml). Blood flow to each domain (ml/min) was calculated as the largest slope in the total volume of enhanced voxels over time. Figure 1 shows an illustration of this workflow which was adopted from previous studies3–5.

Results

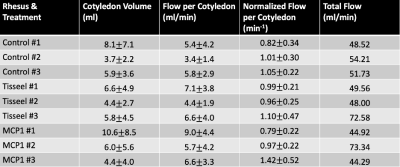

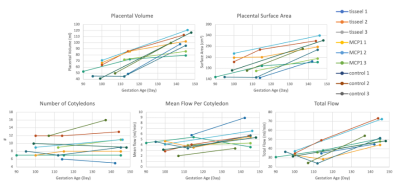

Image acquisition and analysis was successfully conducted for all imaging exams. Unexpectedly, a large number of the injury model placentas deviated from the normal rhesus two-disc pattern (2/3 Tisseel, 2/3 MCP1, 0/3 controls). Initial pathology reports show a wide array of placental injury; detailed quantitative analysis on specific regional inflammation and infarction is in progress.Table 1 shows cotyledon volume, flow per cotyledon, normalized flow per cotyledon (flow over cotyledon volume), and total flow for each subject at the third imaging timepoint. Figure 2 shows longitudinal plots of placental volume, surface area, number of cotyledons, mean flow, and total flow across three imaging timepoints for all nine subjects. The number of cotyledons stays fairly constant with gestation, whereas the other variables have an increasing trend with gestation.

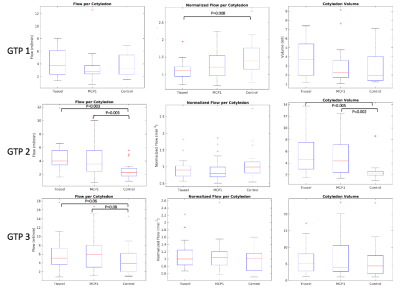

Figure 4 shows box-and-whisker plots of flow, normalized flow, and cotyledon volume at each imaging timepoint. Both Tisseel and MCP1 treatment groups show significantly higher flow and cotyledon volume comparing to the control group at the second gestational timepoint, approximately 15 days after the treatment occurred.

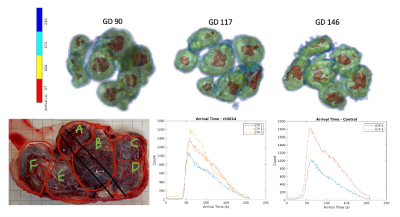

Pathology reports indicate that one Tisseel-treated subject (rh3014) has significant ischemic changes located throughout all levels of the placenta from the decidua basalis to the chronic plate. Figure 3 shows the contrast arrival map for rh3014 at all three gestation timepoints. There is apparent shrinkage in the high-inflow center (arrival time < 20s) of each cotyledon with gestation, suggesting decreased flow. The arrival time histogram also shows a delay in contrast enhancement with increased gestation.

Discussion and Conclusion

This study uses DCE-MRI to assess flow parameters for rhesus macaques injected with MCP1 or Tisseel as models of inflammatory and thrombotic disorders of placenta. The number of cotyledons detected was stable with gestation after ~day 100, which agrees with the findings of Seiter et al,4 indicating that the establishment of functional units in the rhesus is completed by day 100. The arrival maps of rh3014 show a decrease in number of inflow zones, as well as a shrinkage of the center of each inflow zone for a given time point, suggesting that potential tissue infarction and necrosis lead to changes observable with DCE-MRI. Box-and-whisker plots show significantly larger flow per cotyledon was observed at the second timepoint compared with the controls for both treatment groups; this could be due to mechanisms of inflammatory response triggered by sudden local placental insult. A future detailed histopathological analysis of individual subjects is required to assess the extent of injury. Additionally, cotyledon-specific analysis that matches local pathology and MRI data could characterize the sensitivity of DCE MRI for region-specific lesion detection.Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge GE Healthcare for research support of UW-Madison, and funding support from NIH-NICHD (R01HD103443).References

1.Siauve N, Chalouhi GE, Deloison B, et al. Functional imaging of the human placenta with magnetic resonance. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(4 Suppl):S103-14. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2015.06.0452.

2. Roberts JM, Escudero C. The placenta in preeclampsia. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2012;2(2):72-83. doi:10.1016/j.preghy.2012.01.0013.

3. Ludwig KD, Fain SB, Nguyen SM, et al. Perfusion of the placenta assessed using arterial spin labeling and ferumoxytol dynamic contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in the rhesus macaque. Magn Reson Med. 2019;81(3):1964-1978. doi:10.1002/mrm.275484.

4. Seiter DP, Nguyen SM, Morgan TK, et al. Ferumoxytol Dynamic Contrast Enhanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging Identifies Altered Placental Cotyledon Perfusion in Rhesus Macaques. Biol Reprod. Published online August 26, 2022. doi:10.1093/biolre/ioac1685.

5. Frias AE, Schabel MC, Roberts VHJ, et al. Using dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI to quantitatively characterize maternal vascular organization in the primate placenta. Magn Reson Med. 2015;73(4):1570-1578. doi:10.1002/mrm.252646.

6. Deshmane SL, Kremlev S, Amini S, Sawaya BE. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1): an overview. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2009;29(6):313-326. doi:10.1089/jir.2008.00277.

7. Yushkevich PA, Piven J, Hazlett HC, et al. User-guided 3D active contour segmentation of anatomical structures: significantly improved efficiency and reliability. Neuroimage. 2006;31(3):1116-1128. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.015

Figures