0448

Inspecting placental microstructure in pregnancies affected by fetal congenital heart disease1Centre for the Developing Brain, School of Biomedical Engineering and Imaging Sciences, King's College London, London, United Kingdom, 2Biomedical Engineering Department, School of Biomedical Engineering and Imaging Sciences, King's College London, London, United Kingdom, 3Centre for Medical Image Computing, Department of Computer Science, University College London, London, United Kingdom, 4MRC Centre for Neurodevelopmental Disorders, King's College London, London, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: Placenta, Placenta, Diffusion, Microstructure

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is common and associated with abnormal placental development. We used novel diffusion MRI acquisition and analysis techniques to inspect placental microstructure in pregnancies affected by congenital heart disease (CHD), highlighting the potential value of this approach for in-utero identification of how placental development may deviate from normal in CHD.Introduction

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is the most common congenital malformation, affecting ~1% of live-births (1), and is associated with neurodevelopmental impairments persisting into adulthood (2–4). Understanding factors associated with these impairments and linking them to their underlying biological mechanisms is vital if we are to develop interventions to prevent them.The placenta plays a crucial role for fetal development and - amongst other functions - provides the fetus with oxygen and nutrients. There is evidence from both histological and imaging studies that placental development is abnormal in CHD (5–9).

Placental MRI allows non-invasive, in-utero placental analysis, with T2* mapping (10,11) exploiting the blood-oxygenation-level-dependent effect to obtain indirect information on placental oxygenation, and diffusion MRI (dMRI), probing microstructure by investigating the random motion of water molecules, being the most commonly used (12) (Figure 1). Recently, combined acquisition (ZEBRA) and analysis (InSpect) techniques have been developed. ZEBRA allows acquisition of multi-modal data for joint T2*‐ADC analysis in a single, efficient MR scan (12,13). InSpect (13) is an unsupervised learning technique that identifies and maps tissue components in the data based on their spectra.

We aimed to use these tools to explore placental microstructure in-utero in pregnancies affected by CHD, compared to gestation-matched controls.

Methods

8 women with a fetus diagnosed with CHD and 8 gestation-matched controls were recruited as part of The Congenital Heart Disease Imaging Programme (CHIP) [NHS REC 21/WA/0075], and underwent MRI scans in supine position with frequent verbal interaction and continuous physiological observation monitoring. Data was acquired using the combined multi-echo spin-echo diffusion-weighted ZEBRA MR sequence referenced above (12,14), simultaneously probing placental tissue T2* and microstructural properties. Data were acquired at four echo times (TE’s) [78,114,150,186ms], with three diffusion gradient directions at b=[5,10,25,50,100,200,400,600,1200,1600]s/mm2, eight directions at b=18s/mm2, seven at b=36s/mm2, and 15 at b=800s/mm2. Further parameters were field-of-view=300×320×84mm, TR=7s, SENSE=2.5, resolution=3mm3, acquisition time 8m30sec. The acquired data were reconstructed using in-house tools, including bias-correction and motion-correction as previously described (14). Data acquired at the first TE were motion-corrected and the obtained motion parameters applied to all other TE’s to improve robustness and consistency within the data set.Manual regions of interest (ROIs) were defined (15), containing the whole placenta and adjacent uterine wall on the first b=0 image with the lowest TE. We fit the T2*‐ADC model described in Equation 1 voxelwise to the entire data set using an in-house modification of dmipy (16).

Equation 1: S(TE ,b) = S0e-(TE-TEmin)/T*2e-b.ADC

where S0 is the signal at the lowest b-value, TE is the echo time, T*2 is the effective transverse-relaxation time and ADC is the apparent diffusion coefficient.

We identified T2*-ADC spectral components and quantified their spatial variation across the placenta and uterine wall with InSpect, with each component defined by its canonical T2*-ADC spectra (Figure 3) and corresponding mappings (Figure 4). We fit InSpect to all 16 scans simultaneously, fixing seven components, as this was previously shown to best explain the placental T2*-diffusion signal (13).

Results

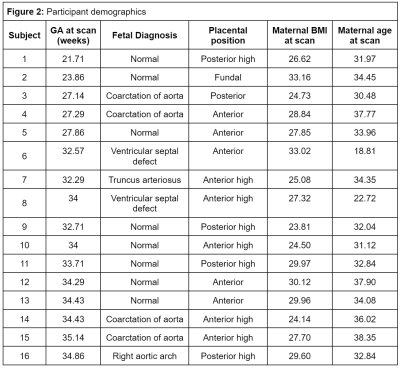

Demographics for all participants are shown in Figure 2.The seven InSpect components, derived from the T2*-ADC spectra (depicted and quantified over gestation in Figure 3) represent different biological tissues, defined according to their microstructural properties.

High T2* values represent well-oxygenated tissue. High ADC values (>0.3 mm2s-1 = Free water) represent perfusing or fast-flowing blood, usually interpreted as being within vasculature. Observing the T2*-ADC spectra and corresponding maps allows initial speculations into the tissue microenvironments associated with each component.

Component 1, for example, which increases in weighting over gestation, with relatively high T2* and moderate ADC values, appears constrained to the edge of placental lobules and may represent perfusing fetal blood. The weighting of component 4 increases noticeably after 30 weeks, has higher ADC and relatively low T2* values, and may thus represent mixed perfusing blood close to cotyledon septal walls. Component 5 increases over gestation, with CHD generally lower than controls, has relatively high T2* and ADC values, and may represent perfusing maternal blood within the placental lobules (Figure 4 & Figure 5).

Discussion

This is one of the first studies using dMRI to explore placental microstructure in-utero in pregnancies affected by CHD. Whilst limited by relatively small subject numbers, a somewhat diagnostically heterogeneous CHD cohort, and a preliminary interpretation of both spectral components and their corresponding dMRI signal weighting, it nonetheless highlights the value of this approach for identifying alterations in placental microstructure in CHD, and other conditions associated with placental pathology. The spatial distribution of oxygen-rich blood may be altered in different types of CHD, for example (Figure 5).It invites speculation as to how each placental tissue component and its corresponding microstructural properties change over gestation, and in CHD, thus allowing an in-vivo exploration of placental microstructure during key periods of fetal development. While histological studies have alluded to such effects, they lack the ability to study functional pathways in-vivo.

Future work should focus on analysing data from larger cohorts of pregnancies affected by CHD, and including those with diagnoses considered to be more severe, as this is where the greatest impairments in placental development are likely to be seen (17–19).

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgments: We are extremely grateful to all participants who generously gave up their time to undergo placental MRI for this study. We are also grateful to radiographers Emer Hughes, Massimo Marenzana, Katie Colford, Peter Murkin, Louise Dillon and Elaine Green for their assistance with ensuring all imaging was performed successfully; to Tom Arichi, Jennie Almalbis, Rebe Martinez-Gonzalez, Joanna Robinson, Megan Quirke, Paul Cawley and Alessandra Maggioni for their support in the MRI department; and to Megan Brace, Stefanie Chan, Michelle Jiang and Zoe Hesketh for their assistance with study recruitment and administration. We thank Dr Elizabeth Swaffield for her excellent depiction of placental anatomy in Figure 1.

Grant Support: This work was supported by grants from the Medical Research Council UK (MR/V002465/1), core funding from the Wellcome/EPSRC Centre for Medical Engineering (WT203148/Z/16/Z), the NIH Human Placenta Project [1U01HD087202-01], EPSRC grant EP/V034537/1, and by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre based at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and University College London.. JH was also supported by a Wellcome Trust Sir Henry Wellcome Fellowship [201374/Z/16/Z] and a UKRI FLF [MR/T018119/1]. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

References

1. EUROCAT. European Platform on Rare Disease Registration. 2020.2. Ilardi D, Ono KE, McCartney R, Book W, Stringer AY. Neurocognitive functioning in adults with congenital heart disease. Congenit. Heart Dis. 2017;12:166–173 doi: 10.1111/chd.12434.

3. Klouda L, Franklin WJ, Saraf A, Parekh DR, Schwartz DD. Neurocognitive and executive functioning in adult survivors of congenital heart disease. Congenit. Heart Dis. 2017;12:91–98 doi: 10.1111/chd.12409.

4. Rodriguez CP, Clay E, Jakkam R, Gauvreau K, Gurvitz M. Cognitive impairment in adult CHD survivors: A pilot study. Int. J. Cardiol. Congenit. Heart Dis. 2021;6:100290 doi: 10.1016/j.ijcchd.2021.100290.

5. Albalawi A, Brancusi F, Askin F, et al. Placental Characteristics of Fetuses With Congenital Heart Disease. J. Ultrasound Med. 2017;36:965–972 doi: 10.7863/ultra.16.04023.

6. Schlatterer SD, Murnick J, Jacobs M, White L, Donofrio MT, Limperopoulos C. Placental Pathology and Neuroimaging Correlates in Neonates with Congenital Heart Disease. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:4137 doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-40894-y.

7. Andescavage NN, Limperopoulos C. Placental abnormalities in congenital heart disease. Transl. Pediatr. 2021;10:2148–2156 doi: 10.21037/tp-20-347.

8. Andescavage N, Yarish A, Donofrio M, et al. 3-D volumetric MRI evaluation of the placenta in fetuses with complex congenital heart disease. Placenta 2015;36:1024–1030 doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2015.06.013.

9. Steinweg JK, Hui GTY, Pietsch M, et al. T2* placental MRI in pregnancies complicated with fetal congenital heart disease. Placenta 2021;108:23–31 doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2021.02.015.

10. Hutter J, Jackson L, Ho A, et al. T2* relaxometry to characterize normal placental development over gestation in-vivo at 3T. Wellcome Open Res. 2019;4:166 doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15451.1.

11. Sørensen A, Hutter J, Seed M, Grant PE, Gowland P. T2*-weighted placental MRI: basic research tool or emerging clinical test for placental dysfunction? Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2020;55:293–302 doi: 10.1002/uog.20855.

12. Slator PJ, Hutter J, Palombo M, et al. Combined diffusion-relaxometry MRI to identify dysfunction in the human placenta. Magn. Reson. Med. 2019;82:95–106 doi: 10.1002/mrm.27733.

13. Slator PJ, Hutter J, Marinescu RV, et al. Data-Driven multi-Contrast spectral microstructure imaging with InSpect: INtegrated SPECTral component estimation and mapping. Med. Image Anal. 2021;71:102045 doi: 10.1016/j.media.2021.102045.

14. Hutter J, Slator PJ, Christiaens D, et al. Integrated and efficient diffusion-relaxometry using ZEBRA. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:15138 doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-33463-2.

15. Yushkevich PA, Piven J, Hazlett HC, et al. User-guided 3D active contour segmentation of anatomical structures: significantly improved efficiency and reliability. NeuroImage 2006;31:1116–1128 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.015.

16. Fick RHJ, Wassermann D, Deriche R. The Dmipy Toolbox: Diffusion MRI Multi-Compartment Modeling and Microstructure Recovery Made Easy. Front. Neuroinformatics 2019;13:64 doi: 10.3389/fninf.2019.00064.

17. Matthiesen Niels B., Henriksen Tine B., Agergaard Peter, et al. Congenital Heart Defects and Indices of Placental and Fetal Growth in a Nationwide Study of 924 422 Liveborn Infants. Circulation 2016;134:1546–1556 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.021793.

18. Snoep MC, Aliasi M, van der Meeren LE, Jongbloed MRM, DeRuiter MC, Haak MC. Placenta morphology and biomarkers in pregnancies with congenital heart disease – A systematic review. Placenta 2021;112:189–196 doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2021.07.297.

19. Binder J, Carta S, Carvalho JS, Kalafat E, Khalil A, Thilaganathan B. Evidence for uteroplacental malperfusion in fetuses with major congenital heart defects. PLoS ONE 2020;15:e0226741 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226741.

Figures