0445

Mapping Placenta Structure and Function with Low-Field MRI1Centre for Medical Image Computing and Department of Computer Science, University College London, London, United Kingdom, 2Centre for the Developing Brain, School of Biomedicial Engineering and Imaging Sciences, King's College London, London, United Kingdom, 3Biomedical Engineering Department, School of Biomedical Engineering and Imaging Sciences, King's College London, London, United Kingdom, 4MR Research Collaborations, Siemens Healthcare Limited, Frimley, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: Placenta, Low-Field MRI

Placental MRI is emerging as a promising adjunct to ultrasound during pregnancy. Low field MRI is appealing for multiple reasons and can support the widespread roll out of placental MRI. Here we provide a proof-of-concept that a quantitative placental imaging technique that has been demonstrated at high-field (1.5T / 3T) – combined T2*-diffusion MRI – is also viable at low field (0.55T). We highlight similarities and differences in low-field maps compared to the current state-of-the-art high-field maps and highlight key areas for future work to realise the potential of low-field placental quantitative MRI during pregnancy.Introduction

Placental MRI is promising for diagnosis, prognosis and monitoring of multiple pregnancy complications including fetal growth restriction (FGR)[1] and pre-eclampsia (PE)[2]. T2* relaxometry is particularly promising, with T2* reduced in FGR and PE[3]. However, there are multiple drawbacks, such as cost and time, that obstruct placental MRI from being a viable screening tool.Low-field MRI has the potential to enable widespread use of placental MRI as it offers multiple advantages over high-field[4] - it is cheaper, has a wider bore whilst maintaining field homogeneity, offers less susceptibility-induced distortions, and is generally easier to deploy. It can hence widen access to antenatal MRI beyond specialist centres.

Multiple pathological structural and functional changes are associated with pregnancy complications[5]. Potential treatments are emerging for complications such as pre-eclampsia[6] and FGR[7]; these will be most effective if diagnosis is early and specific. This motivates a comprehensive placental MRI examination. Combined diffusion-relaxation placental MRI is attractive as it can disentangle multiple complex placental microenvironments, and has shown promise for detecting a range of pregnancy complications at 3T[1,8].

Here we use combined T2*-diffusion to show the feasibility of low-field quantitative placental MRI. We calculate quantitative tissue maps from low-field data and show that they are qualitatively comparable to those derived at high-field. Our proof-of-concept motivates broader studies of low-field quantitative placental MRI for widespread pregnancy monitoring.

Methods

We scanned 5 healthy pregnant participants with a combined diffusion-relaxation scan (ZEBRA[9]) on a 0.55T clinical scanner (Siemens MAGNETOM Free.Max) after informed consent was obtained (meerkat, REC 19/LO/0852). The b-values were 0,50,100,150,300,500,750,1000 s/mm2. Each b-value was acquired with three echo times (TEs), 117,161,205 ms, and three orthogonal gradient directions were acquired per b-value-TE pair. Compared to our previous high-field protocols[8], the number of b-values was reduced and the lowest b-value is 10 times higher, which reduces sensitivity to high diffusivities. We scanned in coronal orientation with respect to the mother with a 6-channel surface coil and in-build 9-channel table coil. Other acquisition parameters: FOV= 400x400x1600mm, 4x4x4mm resolution, Grappa 2, partial Fourier 7/8. The total acquisition time was 7 minutes 20 seconds (55 seconds per b-value). There were 66 volumes in total. We denoised the data using MP-PCA [10] and direction-averaged the data at each b-TE combination.We analysed the direction-averaged data with a joint T2*-ADC model given by

$$S(T_2^*,D)=\exp(-T_E/T_{2}^*)\exp(-bD)$$

we fit this model with self-supervised machine learning, akin to[11].

We also fit InSpect[12], an unsupervised machine learning technique that identifies canonical spectral components and corresponding mappings, to the data. We fit InSpect to all scans simultaneously and specified three canonical spectral components to reflect three putative dominant placental microenvironments: fetal blood, tissue, and maternal blood.

Results

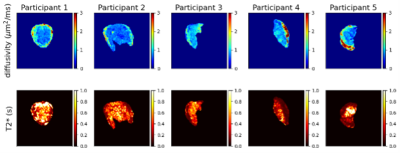

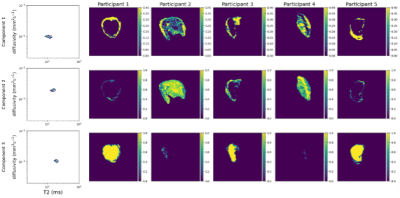

Figure 1 shows T2* and diffusivity maps for the joint T2*-ADC fit. Qualitatively, these maps show features comparable with those seen at higher field strength - the centre of lobules are visible as patches of high T2*, likely reflecting highly oxygenated maternal blood, and there is high diffusivity in the uterine wall, potentially reflecting areas with high volumes of perfusing maternal blood.Figure 2 shows InSpect maps and corresponding T2*-diffusivity spectra for all scans. Component one has T2* around 100ms and diffusivity around 1x10-3mm2s-1, and maps consistently have high intensity in the uterine wall for all scans. Component two has higher T2*, approximately 150ms, and has different spatial patterns in different placentas. Component three has T2* around 200ms, diffusivity 1x10-3mm2s-1 and typically has high intensity in the centre of the placenta.

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that combined T2*-diffusion MRI is viable at 0.55T. We identify T2* and diffusivity maps with comparable patterns to those at higher field strengths, however the range of diffusivity values within maps is lower than in comparable studies at 3T, e.g. [8], likely due to reduced b-value coverage, particularly at very low b-values – the minimum b-value in [8] was 5s/mm2 compared to 50s/mm2 here. However, interestingly, despite having fewer echo times, we observe a comparable, or potentially higher, range in T2* values at 0.55T (Figures 1-2) likely due to the longer relaxation times. This may allow for better quantification of differences in oxygenation in pregnancy complications where T2* is reduced[3].InSpect maps visualise three distinct tissue microenvironments. In contrast with studies at 3T, where components had similar T2* values[12], components are well separated by their T2* values, likely due to longer T2* relaxation times. Components one, three and two have low, high and intermediate T2* values respectively, so potentially reflect low- and high-oxygenated blood, and an intermediate stage of oxygenation.

In addition to the lower cost and higher accessibility, the benefits of low-field MRI address issues specific to MRI in pregnancy – the increased bore size widens access for obese women, and reduced distortion artifacts and B1 inhomogeneity can improve scanning of posterior placentas. This study demonstrates the feasibility of quantitative placenta MRI at 0.55T. The quantitative metrics we derive have the potential to underpin widespread early and specific diagnosis of pregnancy complications such as pre-eclampsia and FGR.

Conclusion

We acquire quantiative placental MRI data at 0.55T and show that existing analysis techniques yield maps with qualitative similarities to data acquired at high-field . This proof-of-concept study can underpin wider deployment of quantitative placental MRI.Acknowledgements

We thank all mothers, midwives, obstetricians, and radiographers who played a key role in obtaining the datasets. Grant support: NIH (1U01HD087202-01); Wellcome Trust (201374/Z/16/Z); EPSRC (EP/V034537/1, EP/M020533/1); UKRI (MR/T018119/1 JH); MRC (MR/V002465/1); NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at UCLH NHS Foundation Trust and UCL; core funding from the Wellcome/EPSRC Centre for Medical Engineering at KCL (WT 203148/Z/16/Z); the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre based at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust and KCL. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.References

[1] R. Aughwane et al., ‘Magnetic resonance imaging measurement of placental perfusion and oxygen saturation in early-onset fetal growth restriction’, BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol., vol. 128, no. 2, pp. 337–345, 2021, doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16387.

[2] A. E. P. Ho et al., ‘T2∗ Placental Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Preterm Preeclampsia: An Observational Cohort Study’, Hypertension, vol. 75, no. 6, pp. 1523–1531, 2020, doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.14701.

[3] A. Sørensen, J. Hutter, M. Seed, P. E. Grant, and P. Gowland, ‘T2*-weighted placental MRI: basic research tool or emerging clinical test for placental dysfunction?’, Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol., vol. 55, no. 3, pp. 293–302, Aug. 2020, doi: 10.1002/uog.20855.

[4] M. Hori, A. Hagiwara, M. Goto, A. Wada, and S. Aoki, ‘Low-Field Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Its History and Renaissance’, Invest. Radiol., vol. 56, no. 11, pp. 669–679, Nov. 2021, doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000810.

[5] T. Y. Khong et al., ‘Sampling and definitions of placental lesions Amsterdam placental workshop group consensus statement’, in Archives of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, 2016, vol. 140, no. 7, pp. 698–713. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2015-0225-CC.

[6] D. L. Rolnik et al., ‘Aspirin versus Placebo in Pregnancies at High Risk for Preterm Preeclampsia’, N. Engl. J. Med., vol. 377, no. 7, pp. 613–622, Aug. 2017, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1704559.

[7] R. Spencer et al., ‘EVERREST prospective study: a 6-year prospective study to define the clinical and biological characteristics of pregnancies affected by severe early onset fetal growth restriction’, BMC Pregnancy Childbirth, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 43–43, Dec. 2017, doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1226-7.

[8] P. J. Slator et al., ‘Combined diffusion-relaxometry MRI to identify dysfunction in the human placenta’, Magn. Reson. Med., vol. 82, no. 1, pp. 95–106, 2019, doi: 10.1002/mrm.27733.

[9] J. Hutter et al., ‘Integrated and efficient diffusion-relaxometry using ZEBRA’, Sci. Rep., vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 15138–15138, Dec. 2018, doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-33463-2.

[10] J. Veraart, D. S. Novikov, D. Christiaens, B. Ades-aron, J. Sijbers, and E. Fieremans, ‘Denoising of diffusion MRI using random matrix theory’, NeuroImage, vol. 142, pp. 394–406, 2016, doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.08.016.

[11] S. Barbieri, O. J. Gurney‐Champion, R. Klaassen, and H. C. Thoeny, ‘Deep learning how to fit an intravoxel incoherent motion model to diffusion‐weighted MRI’, Magn. Reson. Med., vol. 83, no. 1, pp. 312–321, Jan. 2020, doi: 10.1002/mrm.27910.

[12] P. J. Slator et al., ‘Data-Driven multi-Contrast spectral microstructure imaging with InSpect: INtegrated SPECTral component estimation and mapping’, Med. Image Anal., vol. 71, pp. 102045–102045, 2021, doi: 10.1016/j.media.2021.102045.

Figures