0420

Cortical morphometry and hippocampal microstructure predict aging and Alzheimer’s disease progression.1McGill University, Montréal, QC, Canada, 2University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: Alzheimer's Disease, Quantitative Imaging

Morphometric and quantitative MRI metrics have rarely been used simultaneously to characterize healthy aging and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) progression. Here, cortical vertex-wise and hippocampal voxel-wise metrics were extracted to infer atrophy progression (using cortical thickness, surface area or relative Jacobians), myelin and iron contents (T1 and T2* respectively). A data-driven approach was used to parcellate the cortex and the hippocampus. A multivariate statistical technique was used to link hippocampal and cortical metrics to demographics and cognitive scores of interest. Our results suggest that AD-related neural risk is associated with neurodegeneration and microstructural changes in the cortex and hippocampus, respectively.Introduction

While the Canadian population is living longer, one indirect consequence is the increased prevalence of neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Here, we investigate several magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) metrics across the AD spectrum: from healthy aging individuals, individuals with parental AD-history, individuals in prodromal states, and those with frank onset of AD. We combined structural MRI to quantify atrophy and quantitative MRI metrics T1 and T2* to quantify two putative sources of contrast : myelin and iron respectively. Using a matrix decomposition technique we derived joint signatures of covariance across MRI-based measures in the cortex and the hippocampus. We further relate components of covariance to demographics and cognitive information relevant to the AD-spectrum to better understand their relationship to the derived neural components of covariation.Methods

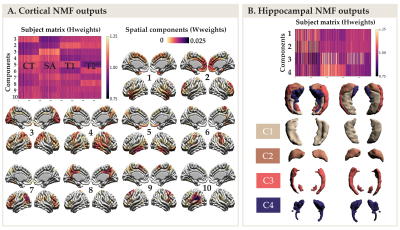

Data from 158 participants were included in this study: (38 healthy controls, 58 cognitively healthy individuals with a parental AD-history [FAMHX], 41 mild cognitive impairment [MCI] and 21 AD; age: 53-84 years old; 62% females; Figure 1A) . Participants were scanned on a 3T Siemens Tim Trio MRI scanner using a 32-channel head coil at the Douglas Research Centre (protocols approved by Research Ethics Board; Figure 1B). T1 maps were acquired using the MP2RAGE sequence2 (TI1=700 ms, TI2=2500 ms, TR=5000 ms, TE=2.91 ms, α1=4, α2=5, bandwidth=240 Hz/pixel, echo spacing=6.8 ms, partial Fourier=6/8, resolution=1 mm isotropic). A 3D multi-echo GRE sequence (12 echoes, TR/TE1/TE12=44/2.84/39.80 ms, echo spacing=3.36 ms; bandwidth=500 Hz/Px; flip angle =15°, resolution = 1 mm isotropic) was used to calculate T2* maps by fitting a monoexponential decay curve (T2* = time at 37% of the signal at TE=0). From MP2RAGE, the T1-weighted UNI images were preprocessed using the minc-bpipe-library pipeline, including N4 bias field inhomogeneity correction5 and then processed through the CIVET pipeline to extract cortical surfaces, thickness (CT) and surface area (SA). T1 and T2* values were extracted and averaged at each vertex across 7 depths between pial and grey/white matter surfaces. To extract voxel-wise hippocampal information, we used deformation-based morphometry to warp all the T1w images and create a group-specific average template using ANTs tools. Relative voxel volume changes were determined from the deformation fields by estimating the Jacobian (J) determinant. The same transformations were used on the T1 and T2* maps to warp all metrics to the template space. An automatic segmentation technique (MAGeT brain algorithm6) was used to generate a hippocampal mask on the template brain and extract voxel-wise J, T1 and T2* (Figure 1C).Non-negative matrix factorization (NMF)7 was used to parcelate the cortex using vertex-wise metrics (CT, SA, T1, T2*) and to parcellate the hippocampus using voxel-wise metrics (J, T1, T2*). NMF decomposes a m x n input matrix into a component matrix W (m x k), and weight matrix H (k x n). W describes component location, while H contains subject-wise weightings describing individual variability of each metric in each component. To select the optimal number of components, we performed a split half analysis for k=2 to k=20 to assess stability and accuracy of decompositions across different granularities8 (Figure 1D). Finally, to test how our components relate to our demographic and cognitive information of interest, we used partial least square (PLS) analysis, a multivariate approach was used to identify a set of latent variables (LVs) that explain patterns of covariance between “brain” and “demographic/cognitive” data. Permutation testing and bootstrap resampling were performed to statistically test each LV and to assess the contribution of the “demographic/cognitive” data (Figure 1E).Results

The NMF parcellations demonstrated patterns similar across hemispheres consisting of 10 cortical components (Figure 2A) and 4 hippocampal components (Figure 2B). NMF also provides subject weight matrices describing both the group and individual level microstructural patterns associated with each component. One significant LV explaining 75% of the variance was obtained with PLS analysis, highlighting an association between our demographic and cognitive pattern (Figure 3A) and our brain pattern (Figure 3B). Overall, we found that being a female, older, in MCI or AD group and with lower cognition was related to lower CT and SA throughout the brain, higher T2* in the precuneus, lower T2* in the dorsomedial prefrontal cortical region, higher T1 and T2* throughout the hippocampus, lower volume in the medial hippocampal component and higher volume in the lateral hippocampal component.Discussion

NMF reduced the dimensionality of our data and provided biologically meaningful components in the cortex and in the hippocampus. PLS explained a large percentage of covariance in our data with one LV demonstrating that being higher age and AD-related risk was principally related to decreased CT and SA in the cortex and higher T1 and T2* (interpreted as demyelination) in the hippocampus.Conclusion

This data-driven approach suggests that AD-related neural risk is associated with neurodegeneration and microstructural changes in the cortex and hippocampus, respectively. Taken together this suggests that microstructural qMRI metrics may be sensitive to the pathology known to start at the earliest stage of the AD progression in the hippocampus.Acknowledgements

A. Bussy received support from the Alzheimer Society of Canada. This research was undertaken thanks in part to funding from the Canada First Research Excellence Fund,awarded to the Healthy Brains, Healthy Lives initiative at McGill University.

M. Chakravarty is funded by the Weston Brain Institute, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and Fondation de Recherches Santé Québec.

References

1. Tardif, C. L. et al. Advanced MRI techniques to improve our understanding of experience-induced neuroplasticity. Neuroimage 131, 55–72 (2016).

2. Marques, J. P. et al. MP2RAGE, a self bias-field corrected sequence for improved segmentation and T1-mapping at high field. Neuroimage 49, 1271–1281 (2010).

3. Stüber, C. et al. Myelin and iron concentration in the human brain: A quantitative study of MRI contrast. NeuroImage vol. 93 95–106 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.02.026 (2014).

4. Cohen-Adad, J. et al. T2* mapping and B0 orientation-dependence at 7T reveal cyto- and myeloarchitecture organization of the human cortex. Neuroimage 60, 1006–1014 (2012).

5. Tustison, N. J. et al. N4ITK: improved N3 bias correction. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 29, 1310–1320 (2010).

6. Pipitone, J. et al. Multi-atlas segmentation of the whole hippocampus and subfields using multiple automatically generated templates. Neuroimage 101, 494–512 (2014).

7. Sotiras, A., Resnick, S. M. & Davatzikos, C. Finding imaging patterns of structural covariance via Non-Negative Matrix Factorization. Neuroimage 108, 1–16 (2015).

8. Patel, R. et al. Investigating microstructural variation in the human hippocampus using non-negative matrix factorization. Neuroimage 207, 116348 (2020).

9. Pini, L. et al. Brain atrophy in Alzheimer’s Disease and aging. Ageing Res. Rev. 30, 25–48 (2016).

10. Yang, H. et al. Study of brain morphology change in Alzheimer’s disease and amnestic mild cognitive impairment compared with normal controls. General Psychiatry vol. 32 e100005 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1136/gpsych-2018-100005 (2019).

Figures