0416

An ultra-fast dementia diagnosis MRI protocol enabled by Wave-CAIPI1Centre for Medical Image Computing (CMIC), Medical Physics & Biomedical Engineering, UCL, London, United Kingdom, 2Advanced Research Computing (ARC) Centre, UCL, London, United Kingdom, 3Dementia Research Centre (DRC), UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology, UCL, London, United Kingdom, 4Department of Brain Repair and Rehabilitation, UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology, UCL, London, United Kingdom, 5Department of Computer Science, Centre for Medical Image Computing (CMIC), University College London, London, United Kingdom, 6Bioxydyn Limited, Manchester, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: Data Acquisition, Dementia

Structural brain imaging is vital in the diagnostic pathway for cognitive disorders and dementias, including the identification of Alzheimer’s disease. MRI is the recommended modality for this but is often not used due to long scan times and lower availability relative to CT. Reduced scan times are needed to enable more widespread adoption of MRI as a first-line modality for cognitive disorders. Our ultra-fast protocol enabled by Wave-CAIPI shows promise in reducing the diagnostic scan time for dementias from around 18 minutes to under 6 minutes whilst retaining clinical utility across several contrasts.Introduction

Structural MRI is the imaging method of choice for dementia diagnosis1; its soft-tissue contrast aids in subtype identification and excluding alternative diseases. However, MRI is more expensive, slower, and less widely available than CT.Patients are often imaged with CT rather than MRI, generating less detailed scans and leading to variations in diagnosis accuracy and disease management. Additionally, with the imminent arrival of disease-modifying therapies for Alzheimer’s disease2,3, demand for diagnostic MRI is set to increase substantially. Serial scanning to enable safety monitoring in emerging therapies3 and to determine eligibility will also stretch resources.

Reducing scan times improves availability by making MRIs easier to schedule, more affordable and easier to tolerate. However, reducing scan-time may cause image degradation that affects clinical usefulness.

We have developed a prototype ultra-fast MRI protocol, based on an optimised 3D parallel imaging approach, which we describe and assess for its potential in reducing scan times in the dementia diagnosis pathway. We evaluate its diagnostic performance against a current standard-of-care protocol, comparing qualitative and quantitative scan metrics in a pilot group of patients.

Methods

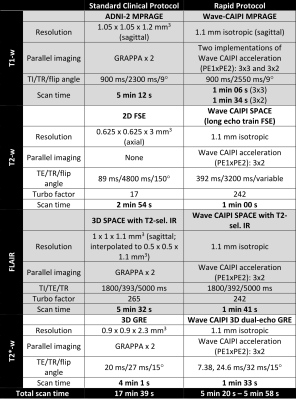

40 participants were recruited from a cognitive disorders clinic at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery (London, UK). All participants were due to have standard clinical 3T MRI as part of their routine diagnostic pathway, ensuring our pilot cohort was representative of the population of interest.Patients were scanned on a 3T Siemens PRISMA system with a 64-channel receiver array coil. The standard-of-care protocol (Fig 1.) included T1w, T2w, FLAIR and T2*/SWI sequences [scan time 17:39 minutes]. We developed a prototype rapid protocol (Fig 1.) that uses Siemens work-in-progress Wave-CAIPI4 (Controlled Aliasing in Parallel Imaging) sequences, enabling scan-time reduction to 5:20 – 5:48 minutes. The rapid sequences were 3D MPRAGE (two variants with different acceleration factors), 3D FLAIR, 3D T2 and 3D T2*. These were interleaved into our clinical protocol to enable comparison of equivalent sequences.

For preliminary qualitative analysis, scans were reviewed by six independent raters (2 neuroradiologists, 2 physicists, 2 neurologists). Paired sequences of both protocols were presented side-by-side. The raters scored each pair for diagnostic utility using a 3-point scale, where +1 favoured the rapid sequence and –1 favoured the standard-of-care sequence. Twelve participants were assessed for each sequence pair except for SWI and rapid 3DT2*, where only 7 were available. In addition, independent visual QC was performed by an experienced clinical trials team on all 40 data sets.

Volumes were calculated from T1w scans using the default cortical reconstruction and volumetric segmentation pipeline in FreeSurfer5 7.3.2. Key volumes (e.g. deep grey matter, cortical grey matter, white matter) for each participant were compared between the two protocols.

Results

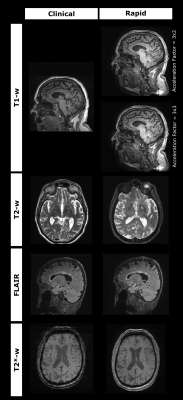

Example standard and rapid scans are shown in fig 2.Side-by-side visual assessment showed a range of diagnostic utility for the rapid scans across sequences (fig. 3). The rapid MPRAGEs were the most diagnostically useful, with the rapid 3D T2 and 3D T2* viewed less favourably. Two raters lowered their rating of the rapid FLAIR due to reduced image ‘sharpness’. Central brightening was observed in the rapid scans, as well as contrast variation in the rapid MPRAGEs around the frontal and temporal lobes.

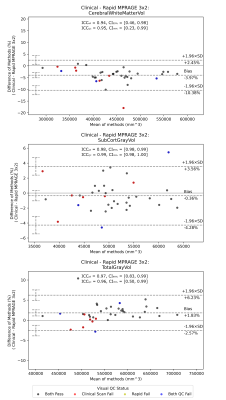

Visual QC generated a failure rate of 22.5% for the clinical T1w sequence, and 7.5% for each of the rapid MPRAGEs – with the primary cause being motion artefacts. Bland-Altman analyses6 comparing volumes (fig 4.) between standard and rapid T1w sequences show little bias, and a scan-re-scan agreement in volume of 5% or less. Outliers are present; these were due to regional segmentation failures and likely caused by either low contrast in the accelerated scans, or motion artefacts in either sequence.

Discussion

The rapid MPRAGE scans were considered good for diagnostic purposes, with the 3x2 accelerated sequence providing more grey-white matter contrast than the shorter 3x3 scan. Central brightening did not affect diagnostic utility in most cases.The rapid 3D T2 was deemed inferior to the clinical sequence, due to the coarser in-plane axial resolution hindering identification of perivascular spaces. Smaller white matter hyperintensities were less observable in rapid 3D FLAIR images, but this did not impact clinical utility. The 3D T2* generated satisfactory images, but the small sample assessed did not include pathologies such as microhaemorrhages.

Some raters felt that the rapid images were less affected by motion artefacts, in agreement with the independent visual QC of T1w scans. We note that different resolutions are likely to have impacted visual comparison, especially between rapid 3D T2 and clinical T2, and rapid 3D T2* and clinical SWI.

The low bias in measured volumes between rapid and clinical T1w scans demonstrates their equivalence. More investigation into the segmentation failures is needed to understand where differences were motion-related or due to other factors (e.g. poor contrast).

Conclusion

Our preliminary results demonstrate that for many contrasts the rapid MRI sequences are diagnostically non-inferior and quantitatively equivalent to the clinical protocol for dementia diagnosis. They practically demonstrate a substantial reduction in scan times, leading to potential cost-savings for providers and better care for patients. Further improvements in data acquisition and image processing may yet yield a better balance of speed, clinical utility, and image quality.Acknowledgements

This study has been funded by Biogen Idec UK. This work is supported by the EPSRC-funded UCL Centre for Doctoral Training in Intelligent, Integrated Imaging in Healthcare (i4health) (EP/S021930/1).References

1. Overview | Dementia: assessment, management and support for people living with dementia and their carers | Guidance | NICE. Accessed November 8, 2022. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng97

2. Cogswell PM, Barakos JA, Barkhof F, et al. Amyloid-Related Imaging Abnormalities with Emerging Alzheimer Disease Therapeutics: Detection and Reporting Recommendations for Clinical Practice. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. Published online August 11, 2022. doi:10.3174/ajnr.A7586

3. LECANEMAB CONFIRMATORY PHASE 3 CLARITY AD STUDY MET PRIMARY ENDPOINT, SHOWING HIGHLY STATISTICALLY SIGNIFICANT REDUCTION OF CLINICAL DECLINE IN LARGE GLOBAL CLINICAL STUDY OF 1,795 PARTICIPANTS WITH EARLY ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE | News Release:2022. Eisai Co., Ltd. Accessed October 25, 2022. https://www.eisai.com/news/2022/news202271.html

4. Bilgic B, Gagoski BA, Cauley SF, et al. Wave-CAIPI for Highly Accelerated 3D Imaging. Magn Reson Med Off J Soc Magn Reson Med Soc Magn Reson Med. 2015;73(6):2152-2162. doi:10.1002/mrm.25347

5. Fischl B. FreeSurfer. NeuroImage. 2012;62(2):774-781. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.01.021

6. Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet Lond Engl. 1986;1(8476):307-310.

Figures