0410

Alzheimer's disease neuropathology contributes to perivascular and parenchymal free water diffusion characteristics1USC Mark and Mary Stevens Institute for Neuroimaging and Informatics, Keck School of Medicine of USC, Los Angeles, CA, United States, 2Research, NeuroScope Inc., Scarsdale, NY, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Alzheimer's Disease, Neurofluids

Disruption of perivascular and interstitial fluid transport in the brain may contribute to the accumulation of toxic metabolic deposits observed in neurodegeneration. However, the relationship between AD neuropathology and free water fluid dynamics are not well understood. Using multi-compartment diffusion models, we assessed the relationship between PET tau and Aβ uptake and free water diffusion properties. We found tau deposition was associated with reduced free water anisotropy in brain regions that undergo neurodegeneration in pre-clinical AD. These findings provide a preliminary link between AD pathology and fluid transfer that may indicate waste clearance functional alterations.Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a debilitating neurodegenerative disorder characterized by profound cognitive impairment and memory loss. Tau neurofibrillary tangles and beta-amyloid (Aβ) plaque deposition are defining features of early AD pathology and can interfere with brain fluid transport. Convective fluid transport through perivascular (PVS) and interstitial spaces play a critical role in brain homeostasis and waste clearance, and disruption of these processes are believed to further contribute to the accumulation of toxic metabolic deposits in the brain during AD progression. Free water fluid dynamics can be measured with multi-compartment diffusion MRI models, such as neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging (NODDI) [1] and tissue tensor imaging (TTI) [2]. We have previously demonstrated altered free water diffusion dynamics in the brain in normal aging [3] and cognitive decline [2]. The goal of this study was to evaluate the contribution of perivascular fluid flow properties on amyloid aggregation and tau deposition measured with PET in patients with cognitive decline. We hypothesize that free water diffusion will be disrupted in brain regions with high tau and amyloid burden.Methods

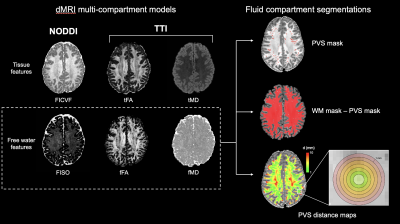

A total of 158 subjects with multi-shell diffusion and PET data from Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative ADNI-3 were considered in this study, including 88 cognitively normal (CN), 46 mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and 24 Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients. PVS were automatically segmented from MP-RAGE T1w images (208x240x256mm, 1x1x1mm resolution) using frangi filters to isolate the tubular morphology of hypo-intense PVS [4]. Additional intensity-based post-processing were performed using FLAIR images (256x256x160mm, 1.2x1x1 mm resolution) to isolated and subtract falsely segmented white matter hyperintensities from the PVS segmentation mask. Multi-shell diffusion MRI data was acquired using the ADNI-3 Advanced protocol (232x232x160mm, 2x2x2mm resolution, TR/TE=3300/71ms, b=500, 1000, 2000 s/mm2, 112 diffusion-encoded directions with 15 b0 volumes interspersed). Motion correction and denoising were implemented with QIT [5]. The NODDI parameter isotropic volume fraction (FISO) [1] was calculated using the spherical mean technique [6] and free water diffusivity measures, fFA and fMD, were computed using TTI [2]. Diffusion maps were sampled within PVS masks, non-PVS white matter masks, and within concentric rings surrounding PVS at 1 mm intervals (Figure 1). Tau PET was also collected by Flortaucipir (18F-AV-1451) and uptake within the entorhinal region, which corresponds to the Braak stage 1 [7], was used to assess the correlation between free water diffusion and early AD pathology. The standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) for tau and Aβ were standardized by dividing the mean of tracer uptake within each region by the uptake in the cerebellar gray matter.Results

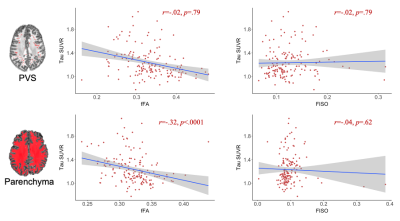

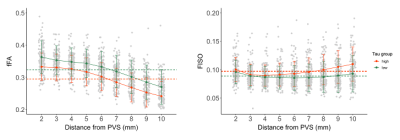

Diagnostic groups had significantly different fFA in the perivascular and interstitial fluid compartments (Figure 2). Patients with AD had significantly higher FISO compared to MCI in the parenchyma (t(68)=-3.01, p=.005), but not in the PVS. Amyloid SUVR in the entorhinal region was not significantly correlated with PVS or parenchymal FISO, fFA or fMD. The correlation between free water diffusion measures and entorhinal tau uptake are shown in Figure 3. fFA was significantly associated with Braak stage 1 tau SUVR after controlling for age, sex, and subject diagnosis (F(154,4)=6.96, p=.009). The association between fFA and tau SUVR was also significant in Braak stage 3/4 regions (F(154,4)=5.25, p=.02) and BRAAK stage 5/6 regions (F(154,4)=5.40, p=.02). Parenchymal fFA was significantly associated with entorhinal tau SUVR after controlling for age and sex (F(155,3)=9.75, p=.002), however this association was no longer significant after correcting for subject diagnosis (F(154,4)=1.78, p=.18). Entorhinal tau SUVR was not significantly associated with FISO or fMD in the PVS or brain parenchyma. A linear mixed-effects model was employed to characterize the relationship between ERC tau SUVR and free water diffusion as a function of distance from the PVS (Figure 4). Subjects were split into a “high” and “low” tau group using the mean entorhinal SUVR as the cut-off value, and found a significant interaction between PVS distance and tau burden on fFA (t(1256)=2.45, p=.014), where fFA decreases faster with distance in the high tau group (b=-.0124, p<.001) compared to the low tau group (b=-.0115, p<.001).Discussion

In the present study, we found free water fluid flow dynamics in the brain are altered as a consequence of tau deposition, but not Aβ. This finding is in contrast to current hypotheses that state PVS enlargement and waste clearance dysfunction in AD is due, in part, to the aggregation of insoluble Aβ in periarterial spaces [8]–[10]. Our findings, however, are supported by previous studies that found PVS morphological changes in the MTL of patients with MCI was independent of amyloid uptake [11], [12], while lower PVS volumes were associated with higher tau PET SUVR [13]. Our finding of selective reductions to perivascular and parenchymal free water fractional anisotropy in patients with high tau burden suggests that tau deposition does not alter the amount of free water, as measured with FISO, but rather affects how the fluid behaves. This association was particularly pronounced in regions that undergo the earliest neuropathological changes corresponding to Braak Stage 1 [14]. Additionally, the association between perivascular fFA and ERC tau uptake remained significant after controlling for subject diagnosis, and suggests that tau may directly contribute to fluid flow within and around the periarterial space.Acknowledgements

The image computing resources provided by the Laboratory of Neuro Imaging Resource (LONIR) at USC are supported in part by National Institutes of Health (grant number P41EB015922). Author KML is supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Institutional Training Grant T32AG058507. This work was supported by NIH grants R01-AG070825 and R01-NS128486.References

[1] H. Zhang, T. Schneider, C. A. Wheeler-Kingshott, and D. C. Alexander, “NODDI: practical in vivo neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging of the human brain.,” Neuroimage, vol. 61, no. 4, pp. 1000–16, Jul. 2012, doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.03.072.

[2] F. Sepehrband, R. P. Cabeen, J. Choupan, G. Barisano, M. Law, and A. W. Toga, “Perivascular space fluid contributes to diffusion tensor imaging changes in white matter,” Neuroimage, vol. 197, pp. 243–254, Jan. 2019, doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.04.070.

[3] K. Lynch, R. Custer, R. Cabeen, F. Sibilia, A. Toga, and J. Choupan, “Age-related changes to perivascular and parenchymal fluid flow dynamics with multi-compartment diffusion MRI,” in International Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine Annual Meeting, 2022.

[4] F. Sepehrband et al., “Image processing approaches to enhance perivascular space visibility and quantification using MRI,” Sci Rep, vol. 9, p. 12351, Aug. 2019, doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-48910-x.

[5] R. P. Cabeen, D. H. Laidlaw, and A. W. Toga, “Quantitative Imaging Toolkit : Software for Interactive 3D Visualization , Data Exploration , and Computational Analysis of Neuroimaging Datasets,” in ISMRM-ESMRMB Abstracts, 2018, pp. 12–14.

[6] R. P. Cabeen, F. Sepehrband, and A. W. Toga, “Rapid and accurate NODDI parameter estimation with the spherical mean technique,” in Proc International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (ISMRM), 2019, p. 3363.

[7] H. Braak and E. Braak, “Evolution of the neuropathology of Alzheimer’s disease,” Acta Neurol Scand, vol. 94, no. SUPPL.165, pp. 3–12, 1996, doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1996.tb05866.x.

[8] H. Mestre, S. Kostrikov, R. I. Mehta, and M. Nedergaard, “Perivascular spaces, glymphatic dysfunction, and small vessel disease,” Clin Sci, vol. 131, no. 17, pp. 2257–2274, 2017, doi: 10.1042/CS20160381.

[9] N. A. Jessen, A. S. F. Munk, I. Lundgaard, and M. Nedergaard, “The Glymphatic System – A Beginner’s Guide,” Neurochem Res, vol. 40, no. 12, pp. 2583–2599, 2015, doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2017.03.040.

[10] J. M. Wardlaw et al., “Perivascular spaces in the brain: anatomy, physiology and pathology,” Nat Rev Neurol, vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 137–153, 2020, doi: 10.1038/s41582-020-0312-z.

[11] F. Sepehrband et al., “Volumetric distribution of perivascular space in relation to mild cognitive impairment,” Neurobiol Aging, vol. 99, pp. 28–43, 2021, doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2020.12.010.

[12] G. Banerjee et al., “MRI-visible perivascular space location is associated with Alzheimer’ s disease independently of amyloid burden,” Brain, vol. 140, pp. 1107–16, 2017, doi: 10.1093/brain/awx003.

[13] F. Sepehrband et al., “Volumetric distribution of perivascular space in relation to mild cognitive impairment,” Neurobiol Aging, vol. 99, pp. 28–43, 2021, doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2020.12.010.

[14] H. Braak and E. Braak, “Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes,” Acta Neuropathol, vol. 82, pp. 239–259, 1991, doi: 10.1109/ICINIS.2015.10.

Figures