0408

Cerebrovascular reactivity (CVR) MRI as a biomarker for small vessel disease related cognitive decline: validation in the MarkVCID Consortium

Peiying Liu1,2, Zixuan Lin1, Kaisha Hazel1, George Pottanat1, Cuimei Xu1, Dengrong Jiang1, Emma Lucke1, Christopher E. Bauer3, Brian T. Gold3, Steven M. Greenberg4, Karl G. Helmer5, Kay Jann6, Gregory A. Jicha3, Joel Kramer7, Pauline Maillard8, Rachel Mulavelil9, Pavel Rodriguez9, Claudia L. Satizabal9, Sudha Seshadri9, Herpreet Singh5, Angel G. Velarde9, Danny J.J. Wang6, Rita R. Kalyani1, Abhay Moghekar 1, Paul B. Rosenberg1, Sevil Yasar1, Marilyn Albert1, and Hanzhang Lu1

1Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States, 2University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States, 3University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, United States, 4Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States, 5Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, United States, 6University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, United States, 7University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, United States, 8University of California, Davis, Sacramento, CA, United States, 9UT Health San Antonio, San Antonio, TX, United States

1Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States, 2University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States, 3University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, United States, 4Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States, 5Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, United States, 6University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, United States, 7University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, United States, 8University of California, Davis, Sacramento, CA, United States, 9UT Health San Antonio, San Antonio, TX, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Dementia, Blood vessels

Small vessel disease (SVD) related vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia (VCID) represent a major factor in cognitive decline in older adults. However, there has not been a validated biomarker for the diagnosis and treatment monitoring of this condition. Recently, the US National Institute on Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), a branch of NIH, funded a MarkVCID consortium, the goal of which is to identify and validate clinical-trial-ready biomarkers for VCID. Cerebrovascular reactivity (CVR) MRI was one of the selected biomarkers that underwent multi-site testing. The present work reports the relationship between CVR and cognitive function, and examines whether the pre-specified hypothesis can be reproduced at each of the sites.INTRODUCTION

Small vessel disease (SVD) related vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia (VCID) represent a major factor in cognitive decline in older adults. However, there has not been a validated biomarker for the diagnosis and treatment monitoring of this condition. Recently, the US National Institute on Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), a branch of NIH, funded a MarkVCID Consortium (https://markvcid.partners.org/), the goal of which is to identify and validate clinical-trial-ready biomarkers for VCID. The study had two phases. In Phase 1 (referred to as the UH2 phase), each site collected and presented single-site data to support the proposal of candidate biomarkers. In Phase 2 (referred to as the UH3 phase), from the proposed biomarkers, the consortium selected 11 for multi-site validation. Cerebrovascular reactivity (CVR) MRI was one of the selected biomarkers that underwent multi-site testing from 2018-2021. The present work reports the relationship between CVR and cognitive function, and examines whether the pre-specified hypothesis can be reproduced at each of the sites.METHODS

CVR as a candidate biomarker in MarkVCIDCVR denotes the ability of cerebral small vessels to dilate in response to vasoactive stimuli, and is thought to directly reflect physiological function of the brain microvasculature. CVR is measured by administering CO2 inhalation while continuously collecting BOLD MRI images. Based on the single-site data collected in Phase 1 [1], CVR was selected to continue into the multi-site testing in Phase 2 of the MarkVCID Consortium study.

Per Consortium protocol, a pre-specified hypothesis was provided before the start of Phase 2, so that the primary analysis method is clearly defined. For CVR, we hypothesized that whole-brain CVR would be associated with a global cognitive measure of Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) after adjusting for age, sex, and education, and this association would be observed in data at each site (i.e., not aggregating data from all sites). It was also pre-specified that each site should have a minimum of 75 participants in order to provide sufficient power for the proposed analysis.

Study procedure

CVR MRI requires the delivery of CO2 gas mixture (5% CO2, 21% O2, 74% N2) to the participant and monitoring of their end-tidal CO2 (EtCO2). Thus, special apparatus and training are needed, in comparison with standard MRI biomarkers. The lead investigative team assembled a standardized box (approximately 2’x2’x2’) that contained all necessary components needed for CO2 delivery and monitoring, and traveled to each site and conducted a 3-hour training session (1 hour of classroom training and 2 hours in the MRI suite) for site certification.

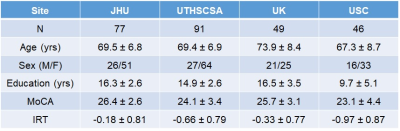

A total of 4 sites and 263 subjects participated in this multi-site study: Johns Hopkins University (JHU, lead site), University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio (UTHSCSA), University of Kentucky (UK), and University of Southern California (USC). A summary of participant characteristics at each site are listed in Table 1. Each site performed an identical CVR procedure, based on the method of Lu et al [2]. Technical assessment of the test-retest reproducibility across sites and MRI manufacturers has been reported previously [3]. BOLD MRI images were acquired during the entire CVR experiment (7 minutes). The scan parameters were: voxel size=3.4×3.4×3.8mm3, 34-36 axial slices for whole-brain coverage, TR=1500ms[4]. A high-resolution 3-D T1-weighted multi-echo MPRAGE was performed (TR/TE/ΔTE/TI= 2530/1.66/1.9/1300 ms, 1×1×1mm3 voxel size, 4 echoes) for anatomic reference [4].

Data processing and analysis

CVR data processing was performed using a cloud-based online processing tool referred to as CVR-MRICloud (https://braingps.mricloud.org/cvr.v5) [5]. The processing method was based the linear regression between the EtCO2 and BOLD time-courses. We primarily focused on whole-brain gray-matter CVR in this report.

As the primary statistical analysis, we conducted multi-linear regression for data on a site-by-site basis. MoCA was used as the dependent variable; CVR was the independent variable; age, sex, and education were covariates. JHU and UTHSCSA were considered separate analysis sites. UKY and USC did not have N=75 participants to be considered separate analysis sites; thus their data were merged to become a joint site, with site included as a covariate.

As a secondary analysis, data from all sites were pooled together and the relationship between CVR and executive function (measured by item response theory, IRT, score [6]), vascular risk factors, and MoCA were studied.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

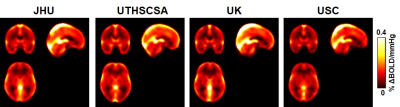

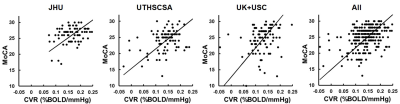

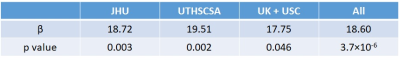

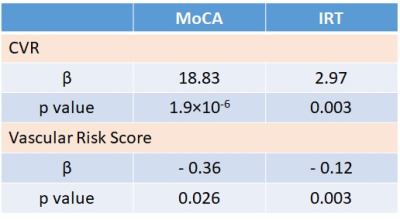

Figure 1 shows averaged CVR maps from each site. Figure 2 shows scatter plots between whole-brain CVR and MoCA for each site, as well as all data points displayed together. Table 2 summarizes the relationship between CVR and MoCA at each site. It can be seen that CVR and MoCA were significantly associated, and this relationship was reproduced at all analysis sites, confirming our pre-specified hypothesis.As secondary analysis results, CVR was found to be associated with executive function (p=0.003), which is the primary cognitive domain affected by small vessel disease (SVD) and VCID.

Importantly, CVR can independently explain variances in MoCA and executive function scores (Table 3), beyond that explained by standard vascular risks scores (hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes mellitus, obesity, and smoking), suggesting that CVR is complementary to classic vascular risks in predicting cognitive decline in SVD/VCID patients.

CONCLUSIONS

CVR is a promising biomarker for SVD/VCID and revealed a reproducible relationship with global cognitive function.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

- Sur S, Lin Z, Li Y, Yasar S, Rosenberg P, Moghekar A, Hou X, Kalyani R, Hazel K, Pottanat G, Xu C, van Zijl P, Pillai J, Liu P, Albert M, Lu H. Association of cerebrovascular reactivity and Alzheimer pathologic markers with cognitive performance. Neurology. 2020 Aug 25;95(8):e962-e972.

- Lu H, Liu P, Yezhuvath U, Cheng Y, Marshall O, Ge Y. MRI mapping of cerebrovascular reactivity via gas inhalation challenges. J Vis Exp. 2014 Dec 17;(94):52306.

- Liu P, Jiang D, Albert M, Bauer CE, Caprihan A, Gold BT, Greenberg SM, Helmer KG, Jann K, Jicha G, Rodriguez P, Satizabal CL, Seshadri S, Singh H, Thompson JF, Wang DJJ, Lu H. Multi-vendor and multisite evaluation of cerebrovascular reactivity mapping using hypercapnia challenge. Neuroimage. 2021 Dec 15;245:118754.

- Lu H, Kashani AH, Arfanakis K, Caprihan A, DeCarli C, Gold BT, Li Y, Maillard P, Satizabal CL, Stables L, Wang DJJ, Corriveau RA, Singh H, Smith EE, Fischl B, van der Kouwe A, Schwab K, Helmer KG, Greenberg SM; MarkVCID Consortium. MarkVCID cerebral small vessel consortium: II. Neuroimaging protocols. Alzheimers Dement. 2021 Apr;17(4):716-725.

- Liu P, Baker Z, Li Y, Li Y, Xu J, Park DC, Welch BG, Pinho M, Pillai JJ, Hillis AE, Mori S, Lu H. CVR-MRICloud: An online processing tool for CO2-inhalation and resting-state cerebrovascular reactivity (CVR) MRI data. PLoS One. 2022 Sep 28;17(9):e0274220.

- Staffaroni AM, Asken BM, Casaletto KB, Fonseca C, You M, Rosen HJ, Boxer AL, Elahi FM, Kornak J, Mungas D, Kramer JH. Development and validation of the Uniform Data Set (v3.0) executive function composite score (UDS3-EF). Alzheimers Dement. 2021 Apr;17(4):574-583.

Figures

Table 1. Characteristics of the participants at each site.

Figure 1: Group-averaged CVR maps from each

site.

Figure 2: Scatter plots between whole-brain CVR

and MoCA.

Table 2: The associations of whole-brain gray

matter CVR with MoCA score at each site.

Table 3: The associations of whole-brain gray

matter CVR and vascular risk factors with MoCA and executive function scores

(IRT) in all subjects.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/0408