0406

Brain Stiffness, Aerobic Fitness, and Memory Performance Differences Between Older Adults with and without Mild Cognitive Impairment1Biomedical Engineering, University of Delaware, Newark, DE, United States, 2Mechanical Engineering, University of Delaware, Newark, DE, United States, 3Kinesiology and Applied Physiology, University of Delaware, Newark, DE, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Alzheimer's Disease, Elastography

Magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) is a robust and sensitive tool used to measure brain mechanical properties that can accurately detect improvements in brain health and function. Exercise and aerobic fitness levels are strongly tied to these brain mechanical properties and their related functionality. In healthy older adults, greater fitness is associated with better memory and increased mechanical integrity of the brain. In a population of older adults with mild cognitive impairment, there is a notable decrease in memory function and aerobic fitness compared to healthy controls, and this decrease is measurable in the mechanical properties of the brain using MRE.Introduction

The consequences of a sedentary lifestyle on overall health has captured the attention of society and the scientific community at large. Research in older adults has shown that regular aerobic exercise improves cardiovascular function and brain health, which may ultimately reduce the risk of dementia [1,2]. Brain mechanical properties measured with magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) sensitively reflect brain health, as exemplified by a study by Schwarb et al. linking aerobic fitness, brain mechanical properties, and memory performance in healthy young adults [3]. Expanding upon that work, a study by Sandroff et al. preliminarily established that exercise intervention has positive effects on memory performance and brain stiffness in subjects with multiple sclerosis, a neurodegenerative disease associated with memory impairment [4]. These two studies were foundational in determining that the relationship between fitness and memory may be used to establish therapeutic interventions for declines in brain health. They show that MRE measures may quantitatively convey the positive influence of aerobic exercise on cognition and overall heath. As such, MRE may be a useful tool in further uncovering how increasing fitness improves brain health in older adult populations. Fitness may have a more profound effect on improving brain health in populations where there is a decline in brain health beyond the scope of natural aging, such as from neurodegenerative diseases like amnestic mild cognitive impairment (MCI), a prodromal stage of Alzheimer’s Disease. Here we examine the relationships between fitness, brain stiffness, and memory performance in older adults with and without MCI.Methods

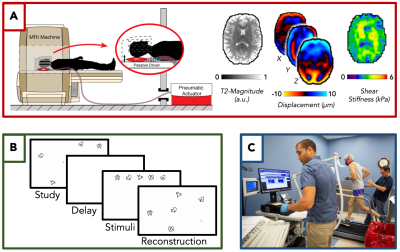

A cohort of 63 cognitively normal, healthy older adult subjects (19M/44F; 60-82 years old) and a cohort of 22 older adult subjects with MCI (7M/15F; 60-89 years old) were assessed for their brain mechanical properties, aerobic fitness, and cognitive performance (Fig. 1). Measurements of brain mechanical properties were performed by inducing 50 Hz vibrations via a Resoundant pneumatic actuator system and passive pillow driver (Rochester, MN) and imaging displacements using a 3D multiband, multishot spiral MRE sequence on a Siemens 3T Prisma MRI scanner (1.25 mm isotropic resolution; 96 slices; 10.75 minutes per scan). Following data collection, a nonlinear inversion (NLI) algorithm was used to convert measured displacement fields into maps of estimated brain tissue stiffness [5] (Fig. 1a). Each subject’s aerobic fitness was determined using a graded exercise test (GXT) wherein a variety of physiological responses are recorded in response to systematically and linearly increasing exercise intensity [6] (Fig. 1b). The GXT is the most widely used tool for assessing cardiovascular fitness, and records measures which reflect an individual’s fitness such as their VO2peak and the percent maximum predicted heart rate achieved during exercise. Cognitive performance was assessed using a spatial reconstruction task to measure relational memory determined by the accuracy of the positioned objects [3]. In this task, five objects with random placements appear on the screen and the subject is asked to study them for 20 seconds, the objects disappear for 4 seconds, then reappear at the top of the screen for the subjects to reconstruct their locations without timed pressure (Fig. 1c).Results

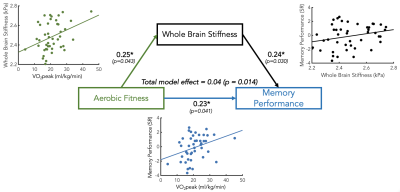

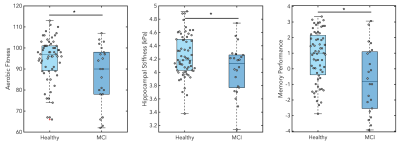

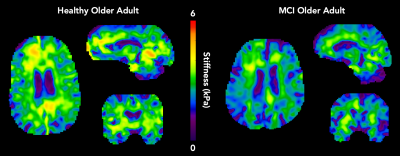

Multifactor ANOVA controlling for sex and age confirmed that in healthy older adults, whole brain stiffness increased with aerobic fitness as assessed by VO2peak (r = 0.25; p = 0.043). VO2peak was also positively associated with memory performance (r = 0.23; p = 0.041). To evaluate the interaction between fitness, memory, and stiffness in this group, mediation analysis of a path model was performed using Mplus 8.8 with standardization and bootstrapping [7]. This analysis revealed that whole brain stiffness has a significant mediating effect on the relationship between aerobic fitness and memory performance (p = 0.014, Fig. 2). This supports the overarching concept that higher aerobic fitness is beneficial to overall cerebral health, which can be objectively measured through brain stiffness with MRE. Furthermore, we examined these measures in a cohort of subjects with MCI. The MCI group exhibited lower fitness, brain stiffness, and memory performance, compared to healthy controls (all p < 0.05, Fig. 3). Brain stiffness differences can be seen plainly between the two groups in a direct comparison of stiffness maps as shown in Figure 4.Discussion and Conclusions

Overall, these findings suggest that a strong positive correlation exists between aerobic fitness, brain health, and cognition in healthy older adults as captured by brain stiffness with MRE. This supports the hypothesis that overall brain health can benefit from higher aerobic fitness, and this research continues to confirm that brain mechanical properties measured with MRE are highly sensitive to brain health. This is reflected in older adults with MCI exhibiting lower brain stiffness, fitness, and memory. We hope to use MRE to both further understand how lifestyle effects like fitness and exercise improve brain health, and provide a sensitive tool for objectively measuring the effects of exercise training and other interventions.Acknowledgements

National Institutes of Health: R01-AG058853, R01-EB027577, and K01-AG054731. Delaware Center for Cognitive Aging Research.References

[1] Tarumi, T. & Zhang, R. Cerebral blood flow in normal aging adults: cardiovascular determinants, clinical implications, and aerobic fitness. J. Neurochem. 144, 595–608 (2018).

[2] Viswanathan, A., Rocca, W. A. & Tzourio, C. Vascular risk factors and dementia: How to move forward? Neurology 72, 368–374 (2009).

[3] Schwarb, H. et al. Aerobic fitness, hippocampal viscoelasticity, and relational memory performance. Neuroimage 153, 179–188 (2017).

[4] Sandroff, B. M., Johnson, C. L. & Motl, R. W. Exercise training effects on memory and hippocampal viscoelasticity in multiple sclerosis: a novel application of magnetic resonance elastography. Neuroradiology 59, 61–67 (2017).

[5]McGarry, M. D. J. et al. Multiresolution MR elastography using nonlinear inversion. Med. Phys. 39, 6388–6396 (2012).

[6] Beltz, N. M. et al. Graded Exercise Testing Protocols for the Determination of VO2max: Historical Perspectives, Progress, and Future Considerations. J. Sports Med. 2016, 1–12 (2016).

[7] Muthén, L. K. and Muthén, B. O. “Mplus User’s Guide: Eighth Edition” Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén (2017).

Figures