0400

Solving the pervasive problem of protocol non-compliance in MR imaging using an open-source tool mrQA

Harsh Sinha1 and Pradeep Reddy Raamana2

1Intelligent Systems Program, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, United States, 2Intelligent Systems Program, Department of Biomedical Informatics, Department of Radiology, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, United States

1Intelligent Systems Program, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, United States, 2Intelligent Systems Program, Department of Biomedical Informatics, Department of Radiology, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Data Acquisition, Data Processing, Protocol Compliance, Quality Control, Quality Assurance

Acquiring MR imaging data by multi-site consortia requires careful monitoring of MR physics protocols. Conventionally, protocol compliance has been an ad-hoc and manual process that is error-prone. Hence, it is often overlooked for the lack of realization that parameters are routinely improvised locally at different sites. Such variation and inconsistencies across acquisition protocols can reduce SNR, & statistical power and, in the worst case, may invalidate the results altogether. We present an open-source tool, called mrQA, to assess protocol compliance and demonstrate the lack of it by analyzing over 20 large open datasets.Background

Large-scale neuroimaging datasets play an essential role in predicting brain-behavior relationships. These large-scale datasets are acquired via engagement with participants over several years using multiple sites and scanners across the country [1]. While neuroimaging-based brain-behavior studies have shown promising results, a well-known obstacle to utilizing these large-scale datasets is that the predictive power is sensitive to data quality [2]. Therefore, there is a need for protocol compliance and quality assurance (QA) in large-scale multi-site datasets. Otherwise, a flawed data collection process may reduce the validity and power of statistical analyses.To alleviate the effects of variation in multi-site consortia, researchers have focused on developing image post-processing techniques to reduce the impact of center effects [3,4,5]. However, not much effort has been devoted to minimizing these inconsistencies in image acquisition protocols. Insufficient monitoring leads to non-compliance in imaging acquisition parameters, including but not limited to flip angle (FA), repetition time (TR), phase encoding direction (PED), sampling bandwidth, and echo time (TE). This problem becomes particularly relevant for analyses from T1/T2 weighted images, which are known to be sensitive to acquisition parameters [7]. In EPI, co-registration with its structural counterpart becomes easier if EPI is compliant with the field map w.r.t field-of-view, pixel bandwidth, and multi-slice mode [6,11]. In DTI, the images acquired with different polarities of PED cannot be used interchangeably as they differ in fractional anisotropy estimates [9]. Thus, predictive analyses conducted without validating sources of error in acquisition metadata may reduce statistical power and, in the worst case, may invalidate results altogether.

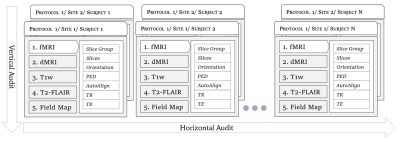

A vigilant oversight, e.g., a regular monitoring service (daily, hourly, or real-time) for aggregating compliance checks on DICOM images at the MRI scanner itself well before the project goes through multiple phases of conversion and reformatting (to lossy formats such as NIfTI) would enable long-term usability and data integrity. The DICOM format offers the best chance to minimize errors in image processing and downstream statistical analyses. It is impractical to hope for data integrity through manual compliance checks, given the ever-increasing datasets, cross-site evaluations, multiple scanners, and varied operational environments, as shown in Figure 1.

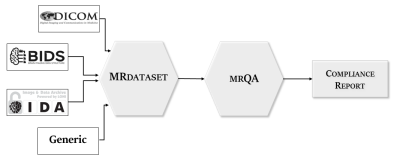

Therefore, we present an open-source tool called mrQA that automates this crucial step in QA. mrQA analyzes acquisition protocols (such as TE, TR, FA, PED) used in an MRI session and checks for compliance across modalities and subjects. mrQA encourages using DICOM-based datasets as they contain complete information about the acquisition. However, mrQA can also interface with other dataset formats, such as the NIfTI-based BIDS datasets, as shown by the schematic in Figure 2.

Results

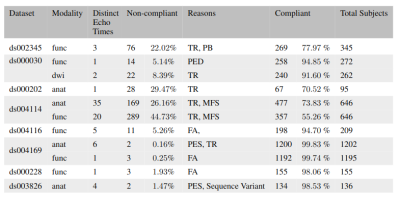

To demonstrate the importance of this issue, we evaluate over 20 open datasets on OpenNeuro [10] to assess the protocol compliance, or lack thereof, in acquisition parameters. Assuming that acquisition for most subjects in a given project follows a predefined standardized protocol, the most frequent value for each parameter is taken as the reference. The exploration is not meant to be a finger-pointing exercise but to discover common pitfalls in MR acquisition that can confound the research we do as a community.Some datasets which exhibit non-compliance are compiled in Table 1. We observe considerable non-compliance in TR and MFS and minor cases in FA, PES, and PED. In addition, some projects had distinct data clusters under the same hood. These data clusters can be repeat experiments with varying acquisition parameters for each subject, e.g., scans with different PED (AP, PA) for DTI or separate tasks in an fMRI. In such cases, none of the subjects would be seen to comply with a single predefined protocol.

We also observe that relying on a non-DICOM source of metadata for analyzing compliance is error-prone. For instance, JSON sidecars (BIDS) are used to complement the inadequate acquisition metadata in the NIfTI header. However, JSON files lack standardization; hence, different datasets disclosed different sets of parameters in the associated JSON files, skipping key parameters like shim, iPAT, and effective echo spacing.

Inconsistency in these acquisition parameters affects MR image contrast in the individual scans, morphometric & connectivity estimates, and other downstream analyses [12]. For instance, typically, large FA produces T1 contrast, and low flip angles produce PD contrast [8]. The choice of TR and TE relative to tissue-specific T1/T2 times is crucial for acquiring T1/T2 images [8], and varying PED helps improve image quality in DTI sequences but at the cost of fractional anisotropy estimates [9]. The impact on signal intensity will depend on the specific tissue in context, but if the subjects have considerable variation, explicit standardization should precede any morphometric analyses. Visually similar images may have the same visual diagnostic accuracy, but images acquired with differing parameter values cannot be used interchangeably for statistical analyses.

Conclusion

We find that several open datasets have inconsistencies in acquisition parameters. As we move towards even larger datasets, automated imaging QA would be critical for valid statistical analyses. mrQA can help automate this process enabling MR labs to move towards practical, efficient, and potentially real-time monitoring of protocol compliance.Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Drs. Ashok Panigrahy, Chan-Hong Moon, Tae Kim, Claudiu Schirda, Victor Yushmanov, and Andrew Reineberg for their comments and helpful discussions. We would also like to thank Tanupat Boonchalermvichien for his software contributions to parsing the DICOM format. We are grateful to the Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center and the XSEDE initiative for providing computational resources for this work. Harsh Sinha is supported by the Intelligent Systems Program Fellowship from the University of Pittsburgh.

References

- Petersen, R. C., Aisen, P. S., Beckett, L. A., Donohue, M. C., Gamst, A. C., Harvey, D. J., Jack, C. R., Jagust, W. J., Shaw, L. M., Toga, A. W., Trojanowski, J. Q., & Weiner, M. W. (2010). Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI): Clinical characterization. Neurology, 74(3), 201–209. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181cb3e25

- Kriegeskorte, N., Simmons, W. K., Bellgowan, P. S. F., & Baker, C. I. (2009). Circular analysis in systems neuroscience: The dangers of double dipping. Nature Neuroscience, 12(5), 535–540. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.2303

- Fortin, J.-P., Cullen, N., Sheline, Y. I., Taylor, W. D., Aselcioglu, I., Cook, P. A., Adams, P., Cooper, C., Fava, M., McGrath, P. J., McInnis, M., Phillips, M. L., Trivedi, M. H., Weissman, M. M., & Shinohara, R. T. (2018). Harmonization of cortical thickness measurements across scanners and sites. NeuroImage, 167, 104–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.11.024

- Friedman, L., Stern, H., Brown, G. G., Mathalon, D. H., Turner, J., Glover, G. H., Gollub, R. L., Lauriello, J., Lim, K. O., Cannon, T., Greve, D. N., Bockholt, H. J., Belger, A., Mueller, B., Doty, M. J., He, J., Wells, W., Smyth, P., Pieper, S., … Potkin, S. G. (2008). Test-retest and between-site reliability in a multicenter fMRI study. Human Brain Mapping, 29(8), 958–972. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.20440

- Gouttard, S., Styner, M., Prastawa, M., Piven, J., & Gerig, G. (2008). Assessment of Reliability of Multi-site Neuroimaging Via Traveling Phantom Study. In D. Metaxas, L. Axel, G. Fichtinger, & G. Székely (Eds.), Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2008 (Vol. 5242, pp. 263–270). Springer Berlin Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-85990-1_32

- Jezzard, P., & Balaban, R. S. (1995). Correction for geometric distortion in echo planar images from B0 field variations. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 34(1), 65–73. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.1910340111

- Gold, G. E., Han, E., Stainsby, J., Wright, G., Brittain, J., & Beaulieu, C. (2004). Musculoskeletal MRI at 3.0 T: Relaxation Times and Image Contrast. American Journal of Roentgenology, 183(2), 343–351. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.183.2.1830343

- Weishaupt, D., Köchli, V. D., & Marincek, B. (2003). How does MRI work? Springer Berlin Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-07805-1

- Kennis, M., van Rooij, S. J. H., Kahn, R. S., Geuze, E., & Leemans, A. (2016). Choosing the polarity of the phase-encoding direction in diffusion MRI: Does it matter for group analysis? NeuroImage: Clinical, 11, 539–547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2016.03.022

- Markiewicz, C. J., Gorgolewski, K. J., Feingold, F., Blair, R., Halchenko, Y. O., Miller, E., Hardcastle, N., Wexler, J., Esteban, O., Goncalves, M., Jwa, A., & Poldrack, R. A. (2021). OpenNeuro: An open resource for sharing of neuroimaging data [Preprint]. Neuroscience. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.28.450168

- Jezzard, P. (2012). Correction of geometric distortion in fMRI data. NeuroImage, 62(2), 648–651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.09.010

- Onishi, N., Li, W., Gibbs, J., Wilmes, L. J., Nguyen, A., Jones, E. F., Arasu, V., Kornak, J., Joe, B. N., Esserman, L. J., Newitt, D. C., & Hylton, N. M. (2020). Impact of MRI Protocol Adherence on Prediction of Pathological Complete Response in the I-SPY 2 Neoadjuvant Breast Cancer Trial. Tomography, 6(2), 77–85. https://doi.org/10.18383/j.tom.2020.00006

Figures

Figure 1. Overview of the relationship between various levels relevant to protocol compliance checks such as subject, modality, site, etc. Horizontal audit checks for compliance across subjects in a given modality (i.e. compliant w.r.t a pre-defined protocol) whereas vertical audit checks if a single subject is compliant across all the acquired modalities.

Figure 2. We developed the MRDataset library and data structure to interface with and support the most popular MR imaging dataset formats. MRDataset offers a unified interface to access acquisition information as well as metadata such as modalities, subjects, and sessions in a hierarchical structure to represent an MR imaging dataset. This interface is in turn used for generating protocol compliance reports via mrQA.

Table 1. Evaluation of public datasets on OpenNeuro (denoted by accession number in column 1) exhibiting some lack of protocol compliance. The frequent source of non-compliance includes Repetition Time (TR), Phase Encoding Steps (PES), Phase Encoding Direction (PED), Pixel Bandwidth (PB), Magnetic Field Strength (MFS) and Flip Angle (FA). We observe considerable non-compliance in TR, and MFS and minor cases in FA, PES, and PED.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/0400