0397

Reproducibility of the bSTAR sequence and open-source implementation1Biomedical Engineering, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, United States, 2Department of Radiology, University of Basel Hospital, Basel, Switzerland, 3Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Lung, Low-Field MRI

The reproducibility of scientific reports is crucial to advancing human knowledge. This abstract is a response to the 2023 ISMRM Challenge “Repeat it With Me: Reproducibility Team Challenge”. We reproduce the bSTAR sequence, a very short-TR, 3D half-radial dual-echo bSSFP sequence, providing banding-artifact free images within a large FOV. bSTAR imaging is attractive for various applications at low field and especially attractive for lung parenchyma imaging due to the prolonged T2’. We have successfully reproduced the bSTAR method, and figures with comparable image quality compared to published literature. We provide an open-source implementation using Pulseq and BART.INTRODUCTION

The reproducibility of scientific reports is crucial to advancing human knowledge. This abstract is a response to the 2023 ISMRM Challenge “Repeat it With Me: Reproducibility Team Challenge”. We reproduce the bSTAR sequence (1,2), and provide an open-source implementation.bSTAR is a 3D half-radial dual-echo balanced steady-state free precession (bSSFP) sequence that has been proposed for free-breathing non-ECG-triggered thoracic imaging with extremely short TR at 1.5T (1,2). It is especially attractive for lung parenchyma imaging at low field due to the prolonged T2’ (3). bSTAR is suitable for various applications at low field strengths because a bSSFP sequence is instrumental in achieving high SNR compensating for reduced equilibrium polarization; and achieving a short TR for bSSFP is extremely important to avoid banding artifacts caused by enhanced concomitant fields.

We reproduce the bSTAR sequence for thoracic imaging at 0.55T using vendor neutral open-source frameworks to enable code sharing across different institutions, vendors, and scanner software versions. We used the Pulseq framework (4) for pulse sequence implementation, and Berkeley Advanced Reconstruction Toolbox (BART) for image reconstruction (5).

METHODS

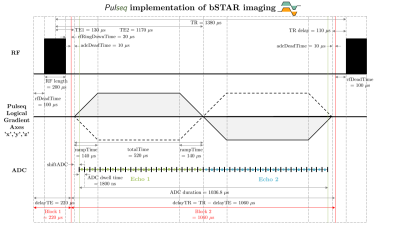

Pulse sequence:A free-running non-ECG-triggered bSTAR sequence was implemented with the Pulseq framework (4). A detailed pulse sequence diagram for bSTAR imaging is illustrated in Figure 1. Both wobbling Archimedean spiral pole trajectory (WASP) (3) and a spiral phyllotaxis trajectory (SP) (6) were implemented.

Pulseq implementation:

The Pulseq framework (abbreviated as Pulseq) defines RF, gradient, ADC, and delay events as basic components of a pulse sequence. Pulseq provides a Cartesian coordinate system [x, y, z] and referred to as Pulseq logical x y and z axes. We interpreted this coordinate system as vendor’s logical axes [RO, PE, SL] using “old/compat” option in the “Orientation mapping” parameter. Gradients and rotation matrices were defined using [PE, RO, SL] as the first, second, and third coordinate in a logical coordinate system to comply with our vendor’s coordinate transformation from a logical coordinate system to a physical coordinate system. A gradient event on different axis is considered as a separate event.

Experiments:

All imaging experiments were performed on a whole-body 0.55T scanner (prototype MAGNETOM Aera; Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) with gradients capable of 45mT/m amplitude and 200 T/m/s slew rate. A six-element body coil (anterior) and six elements from an 18-element spine coil (posterior) were used for signal reception. The default shim setting (tune-up mode) was used. Two healthy volunteers (1 male and 1 female) were scanned under a protocol approved by our institutional review board after providing written informed consent.

Phantom study:

An ISMRM/NIST system phantom (7) was scanned with WASP and SP trajectories. Imaging parameters were: TR = 1.38 ms, TE1 = 0.13 ms, TE2 = 1.17 ms, RF duration = 200 µs, FA = 25°, FOV = 340 x 340 x 340 mm3, isotropic resolution = 1.6 x 1.6 x 1.6 mm3, bandwidth = 1929 [Hz/px], number of interleaves = 89/88, half-radial projections = 31152, and total scan time = 43 sec.

Human study:

In one subject, a 50-sec breathhold acquisition during end-expiration was performed using the SP trajectory with 89 interleaves (39961 half-radial projections). This volunteer was capable of very long breatholds in order to facilitate retrospective undersampling experiments that are planned. In one subject, a 23-sec breathhold acquisition during end-expiration was performed using the WASP trajectory with 4 interleaves (17000 half-radial projections).

Trajectory measurements:

K-space trajectories along +X, -X, +Y, -Y, +Z and -Z physical axes were measured with Duyn’s method (8) and a recently proposed method by Zhao et al. (9). 3D radial half-spokes were calculated with a linear combination of measured trajectories.

Reconstruction:

Image reconstruction was performed with compressed sensing SENSE reconstruction implemented in the Berkeley Advanced Reconstruction Toolbox (BART). A wavelet transform (Daubechies 2) was used for a sparse transform with a regularization parameter of 0.005.

RESULTS

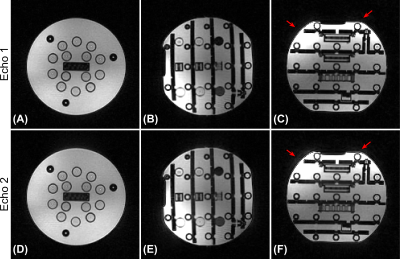

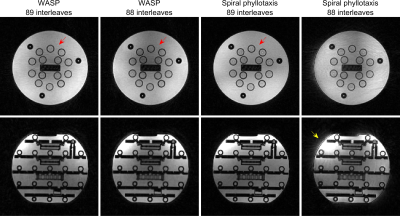

Figure 2 reproduces Figure 3 of Ref. 2 using an ISMRM/NIST system phantom. Image reconstructions from both echoes show no visible artifacts including banding artifacts and geometric distortion due to inaccuracies in k-space trajectories.Figure 3 reproduces Figure 4 of Ref. 1 using an ISMRM/NIST system phantom. WASP trajectories with 88 and 89 interleaves did not create noticeable eddy current artifacts, demonstrating its flexibility in the design of 3D radial trajectory patterns.

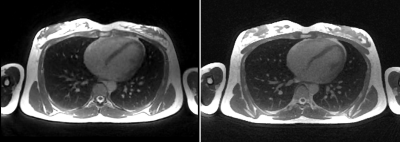

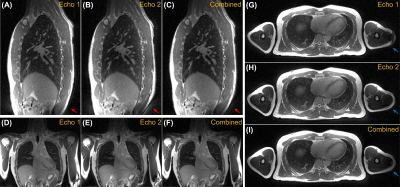

Figure 4 shows the exemplary bSTAR images of a male volunteer acquired during end-expiratory brearthhold. Banding artifacts are not visible within the FOV of interest.

Figure 5 compares image reconstructions by Pulseq bSTAR and original bSTAR (implemented in Siemens’ IDEA programming language). Each method acquired data separately with its own pulse sequence and reconstructed images with its reconstruction pipeline. DICOM images were created at the end of each reconstruction pipeline and compared in a DICOM reader.

DISCUSSION & CONCLUSION

We have successfully reproduced the bSTAR method, and figures with comparable image quality compared to published literature (1,2). This study also demonstrates the power of open-source frameworks, specifically Pulseq, because designing a pulse sequence in a vendor proprietary environment requires expertise and tremendous effort.Acknowledgements

We acknowledge grant support from the National Science Foundation (#1828736) and research support from Siemens Healthineers.

References

1. Bauman G, Bieri O. Balanced steady-state free precession thoracic imaging with half-radial dual-echo readout on smoothly interleaved archimedean spirals. Magn Reson Med 2020;84:237–246 doi: 10.1002/MRM.28119.

2. Bieri O, Pusterla O, Bauman G. Free-breathing half-radial dual-echo balanced steady-state free precession thoracic imaging with wobbling Archimedean spiral pole trajectories. Z Med Phys 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.zemedi.2022.01.003.

3. B Li, NG Lee, SX Cui, KS Nayak. "Lung parenchyma transverse relaxation rates at 0.55 Tesla." Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. accepted.

4. Layton KJ, Kroboth S, Jia F, et al. Pulseq: A rapid and hardware-independent pulse sequence prototyping framework. Magn Reson Med 2017;77:1544–1552 doi: 10.1002/MRM.26235.

5. Uecker M, Ong F, Tamir JI, et al. Berkeley Advanced Reconstruction Toolbox. In Proceedings of the 18th Annual Meeting of ISMRM, 2015. p. 2486.

6. Delacoste J, Chaptinel J, Beigelman-Aubry C, Piccini D, Sauty A, Stuber M. A double echo ultra short echo time (UTE) acquisition for respiratory motion-suppressed high resolution imaging of the lung. Magn Reson Med 2018;79:2297–2305 doi: 10.1002/MRM.26891.

7. Stupic KF, Ainslie M, Boss MA, et al. A standard system phantom for magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Med 2021;86:1194–1211 doi: 10.1002/MRM.28779.

8. Duyn JH, Yang Y, Frank JA, van der Veen JW. Simple correction method for k-space trajectory deviations in MRI. J Magn Reson 1998;132:150–153 doi: 10.1006/JMRE.1998.1396.

9. Zhao X, Lee H, Song HK, Cheng CC, Wehrli FW. Impact of gradient imperfections on bone water quantification with UTE MRI. Magn Reson Med 2020;84:2034–2047 doi: 10.1002/MRM.28272.

Figures

Figure 2. Reproduction of Figure 3 of Ref. 2 using an ISMRM/NIST system phantom. Coronal (A and D), sagittal (B and E), and axial (C and F) views for the first echo (top row) and the second echo (bottom row). A spiral phyllotaxis pattern with 89 interleaves was used to minimize eddy currents. The axial view of the second echo shows subtle, but enhanced artifacts compared with the first echo (red arrows). We speculate that concomitant fields accumulated during the first echo in conjunction with the zeroth-order eddy currents are sources of this artifact.

Figure 3. Reproduction of Figure 4 of Ref. 1 using an ISMRM/NIST system phantom. Image reconstructions from the first echo are displayed. WASP trajectories with 89 and 88 interleaves did not create noticeable eddy current artifacts. The SP trajectory with 88 interleaves contains severe eddy current artifacts due to its non-smooth trajectory pattern. The shading pattern of SP with 89 interleaves (red arrow) is not identical to that of WASP trajectories. The eddy current artifacts (yellow arrow) create a geometric distortion that resembles an artifact caused by trajectory error.

Figure 4. Exemplary Pulseq bSTAR images of a healthy volunteer acquired during one 50-sec end-expiratory breathhold. Sagittal (A, B, C), coronal (D, E, F), and axial (G, H, I) views of the first, second, and combined echoes. Images of the second echo show noticeable artifacts (red arrow), which could be attributed to eddy currents created during the acquisition of the first echo. Banding artifacts (blue arrow) are located away from the FOV of interest (thoracic area). Echo combined images show improved SNR without noticeable geometric distortion contributed by the second echo.