0387

K-band: A self-supervised strategy for training deep-learning MRI reconstruction networks using only limited-resolution data1Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, Image Reconstruction, MRI reconstruction, self-supervised, deep learning

Although Deep learning (DL) techniques are powerful for MRI reconstruction, their development is hindered by the need for large training datasets. We propose a self-supervised method for training DL reconstruction networks using only limited-resolution data, acquired in k-space “bands”, which are generally easier to acquire than variable-density full-resolution data. Although the network is trained using low-resolution data, during inference it can reconstruct high-resolution images. Comprehensive experiments demonstrate that k-band is robust to various acceleration factors, outperforms two other methods trained on low-resolution data, and obtains comparable performance with SSDU and MoDL, while also reducing the need for full-resolution data.INTRODUCTION

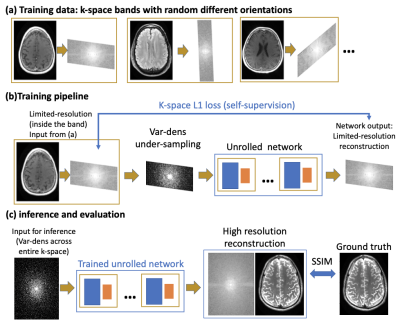

Deep learning (DL) techniques have recently emerged as powerful tools for MRI reconstruction3,11,12, showing improved performance over classical compressed sensing methods1. However, a recurrent challenge in developing DL reconstruction methods is the need for large, fully sampled MRI datasets for training, as using processed data can lead to biased results10. Acquisition of fully sampled raw MRI data can be challenging and sometimes impractical, especially in dynamic MRI, where body movement, respiration, and cardiac motion cause artifacts9. Thus, there is growing interest in developing self-supervised methods that can be trained using only limited data; SSDU2 is a recent example.We propose a new self-supervised method, dubbed “k-band”, which can be trained using only limited-resolution k-space data (Figure 1a). The training examples consist of k-space samples located in “bands”, which have full resolution in only one dimension (Figure 1b). Importantly, the band orientation changes randomly across examples, hence the network is ultimately exposed to all k-space areas; this is similar to conducting stochastic gradient descent across many k-space subsets. During inference, however, the network is not limited to low-resolution data. It receives variable-density undersampled data from the entire k-space (Figure 1c). Since the training covered all k-space areas, the network can reconstruct high-resolution images even though it never saw such images during training. Our strategy thus eliminates the need for acquiring training data with high resolution in two k-space dimensions. This is an advantage over other methods (e.g., SSDU), which require high resolution in all k-space dimensions. Another advantage is that bands can be acquired easily, without modifying the pulse sequence, by changing the phase encoding resolution and using oblique planes.

METHODS

We simulate “k-band” acquisition by multiplying fully sampled data with band masks, with random angles sampled uniformly (Figure 1a). To perform self-supervision in the k-space domain, we further undersample the k-space band with a variable density Poisson disc mask; this data is used as input. For supervision we use all the samples within the band. To compensate for over-exposure to low-frequency k-space areas, we introduce a special loss-weighting, calculated by taking the normalized inverse of the sum of all bands.Our k-band strategy is agnostic to the network architecture. Here we used an unrolled MoDL3 architecture with ResNet8 blocks. We also used the PyTorch13, DeepInPy4, and SigPy14 packages. Data was obtained from FastMRI5. For the knee (brain) data, we used 4 (10) unrolls and 6 (8) residual blocks, where we cropped empty background regions in the brain data to fit more unrolls on GPUs. We used L1 loss, computed in k-space, only inside bands.

We compared our k-band method with four other methods: (1) MoDL (a fully supervised baseline)3, (2) SSDU, a state-of-the-art self-supervised method2, (3) a “square baseline”, trained on low-resolution data obtained in a square center of k-space, as proposed in [2], and (4) a “vertical baseline”, trained on low-resolution k-space bands at a single angle. For a fair comparison, we trained all networks using the same amount of k-space samples (with their corresponding sampling patterns), and the same loss (k-space L1 loss). Reconstruction quality was quantified using the Normalized Mean Square Error (NMSE) and Structural Similarity Index (SSIM)15.

RESULTS

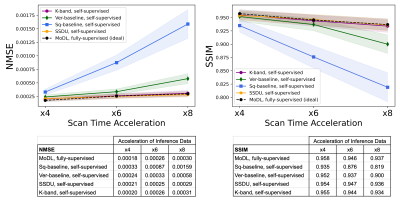

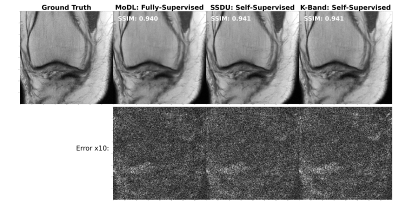

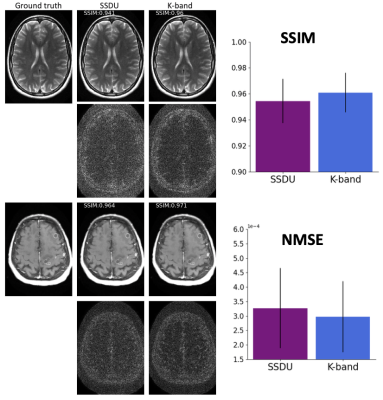

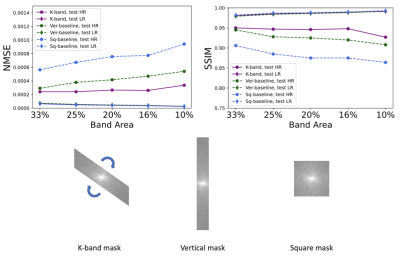

(Figure 2). We compared the k-band method with the vertical and square baselines using the fastMRI knee data. The input acceleration was 5x. To demonstrate the effect of distribution shift between training and test data, we ran inference twice, using low-resolution variable-density data from bands, and high-resolution variable-density data from the entire k-space. The results indicate that: (i) k-band provides an advantage compared to the baseline methods, (ii) it has the smallest performance gap between the two data types, and (iii) k-band also shows robustness to smaller bands, with stable performance over band widths ranging from 10% to 33% of k-space.(Figures 3, 4, 5). We compared k-band with MoDL, SSDU, vertical, and square baselines on the fastMRI dataset for varying variable-density accelerations. The results show that k-band performs comparably to SSDU and MoDL, both statistically and visually.

DISCUSSION

We introduce the k-band strategy for training MRI reconstruction networks using only limited-resolution data. Comprehensive experiments demonstrate that k-band has stable performance across a range of acceleration factors and band widths, outperforms two baseline methods trained on low-resolution data, and is less sensitive to distribution shifts. Moreover, k-band performs comparably to SSDU and MoDL, with an advantage of reducing the need for full-resolution training data.An additional advantage of our strategy is that it enables the acquisition of data in bands, which are localized in k-space. This is easier to collect than variable-density acquisitions, e.g., in EPI acquisitions, and bands are less prone to acquisition artifacts. Moreover, band acquisition can be accelerated using equispaced undersampling and Parallel Imaging6,7. This approach is less practical when the entire k-space should be covered, because PI methods perform poorly when equispaced lines are highly separated.

In summary, our strategy offers a practical solution for training networks using only limited-resolution data, which can be acquired efficiently. This can pave the way towards easier acquisition of training datasets in dynamic MRI and other challenging regimes, and development of new DL techniques.

Acknowledgements

H.Q. and F.W. contributed equally to this work.

The authors would like to acknowledge funding from grants U24EB029240, U01EB029427, R01EB009690, GE Healthcare, and the Weizmann Institute Women’s Postdoctoral Career Development Award in Science.References

[1] Lustig, Michael, et al. "Compressed sensing MRI." IEEE signal processing magazine, 25.2 (2008): 72-82.

[2] Yaman, Burhaneddin, et al. "Self-supervised learning of physics-guided reconstruction neural networks without fully sampled reference data." Magnetic resonance in medicine, 84.6 (2020): 3172-3191.

[3] Aggarwal, Hemant K., Merry P. Mani, and Mathews Jacob. "MoDL: Model-based deep learning architecture for inverse problems." IEEE transactions on medical imaging, 38.2 (2018): 394-405.

[4] Tamir, Jonathan I., et al. "DeepInPy: Deep Inverse Problems in Python." ISMRM Workshop on Data Sampling and Image Reconstruction, 2020.

[5] Zbontar, Jure, et al. "fastMRI: An open dataset and benchmarks for accelerated MRI." arXiv preprint, arXiv:1811.08839 (2018).

[6] Griswold, Mark A., et al. "Generalized autocalibrating partially parallel acquisitions (GRAPPA)." Magnetic Resonance in Medicine: An Official Journal of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 47.6 (2002): 1202-1210.

[7] Pruessmann, Klaas P., et al. "SENSE: sensitivity encoding for fast MRI." Magnetic Resonance in Medicine: An Official Journal of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 42.5 (1999): 952-962.

[8] He, Kaiming, et al. "Deep residual learning for image recognition." Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016.

[9] Knoll, Florian, et al. "Deep-learning methods for parallel magnetic resonance imaging reconstruction: A survey of the current approaches, trends, and issues." IEEE signal processing magazine, 37.1 (2020): 128-140.

[10] Shimron, Efrat, et al. "Implicit data crimes: Machine learning bias arising from misuse of public data." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119.13 (2022): e2117203119.

[11] Wang, Shanshan, et al. "Accelerating magnetic resonance imaging via deep learning." 2016 IEEE 13th international symposium on biomedical imaging (ISBI), IEEE, 2016.

[12] Hammernik, Kerstin, et al. "Learning a variational network for reconstruction of accelerated MRI data." Magnetic resonance in medicine, 79.6 (2018): 3055-3071.

[13] Paszke, Adam, et al. "Pytorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library." Advances in neural information processing systems, 32 (2019).

[14] Ong, Frank, and Michael Lustig. "SigPy: a python package for high performance iterative reconstruction." Proceedings of the ISMRM 27th Annual Meeting, Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Vol. 4819. 2019.

[15] Wang, Zhou, et al. "Image quality assessment: from error visibility to structural similarity." IEEE transactions on image processing, 13.4 (2004): 600-612.

Figures

Figure 2: Comparison of k-band with two reference methods. The band area is the fraction of k-space data used for supervision (per image). To demonstrate the distribution shift between training and test data, inference was done twice, using low-resolution (LR) and high-resolution (HR) data. Note that while all three methods show reduced performance for HR data, k-band does substantially better than the other methods and shows the smallest sensitivity to the distribution shift.