0367

DEveloping Blood-Brain barrier arterial spin labeling as a non-Invasive Early biomarker (DEBBIE)1Department of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, Amsterdam UMC, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2National University of Singapore and National University Health System, Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, Singapore, Singapore, 3Department of Psychology, University of Oslo, Center for Lifespan Changes in Brain and Cognition, Oslo, Norway, 4Fraunhofer-Insitute for Digital Medicine MEVIS,, Bremen, Germany, 5Clinics of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, University of Oslo, Department of Physics and Computational Radiology, Oslo, Norway, 6University College London, Dementia Research Center, London, United Kingdom, 7University of Auckland, School of Psychology and Centre for Brain Research, Auckland, New Zealand, 8Lawson Health Research Institute, London, ON, Canada, 9Department of Medical Imaging, Ghent University Hospital, Gent, Belgium, 10Bogazici University, Institute of Biomedical Engineering, Istanbul, Turkey, 11Clinics of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, Oslo University Hospital, Department of Physics and Computational Radiology, Oslo, Norway, 12Department of Neurology, Akershus University Hospital, Lørenskog, Norway, 13Technische Universität Dresden, Department of Neuroradiology, University Hospital Carl Gustav Carus, Dresden, Germany, 14mediri GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany, 15University College London, Queen Square Institute of Neurology and Centre for Medical Image Computing (CMIC), London, United Kingdom, 16University of Oslo, Institute of Clinical Medicine, Campus Ahus, Lørenskog, Norway, 17Institute of Radiopharmaceutical Cancer Research, Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf, Dresden, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: Alzheimer's Disease, Aging

One of the earliest signs of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the loss of blood-brain barrier (BBB) integrity. Arterial spin labeling (ASL) MRI is a non-invasive way to measure perfusion and several other hemodynamic and physiological parameters, including vascular permeability. The DEveloping BBB-ASL as non-Invasive Early biomarker (DEBBIE) consortium aims to develop and integrate innovative techniques to allow robust BBB permeability assessments by ASL to develop a sensitive, non-invasive, and early biomarker for AD and related dementias. This work summarizes our planned efforts to develop and establish an MRI-based BBB permeability biomarker.1. Introduction

Cognitive impairment associated with aging is a major public health challenge, with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) being one of the primary causes. One of the earliest microvascular observations in the pathogenesis of AD and related dementias is the loss of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) integrity(1,2). The BBB is a cellular structure that protects the brain by regulating the transport of molecules from the blood to the brain(3). In AD, BBB disruption is associated with AD’s inflammatory pathway, making BBB integrity a potential early biomarker for AD(4–9).Recently developed non-invasive MRI techniques to probe the BBB integrity, such as multi-echo arterial spin labeling (BBB-ASL)(10), use magnetically labeled blood water as an endogenous tracer. BBB-ASL quantifies BBB water exchange by separating the ASL signal fractions in the intra- and extravascular compartments based on their differences in transversal relaxation time (T2). BBB-ASL’s non-invasiveness facilitates widespread use, and with a lower molecular weight than a typical MR contrast agent, it has the potential to detect earlier, subtle stages of BBB breakdown in AD.

We formed a consortium for DEveloping BBB-ASL as a non-Invasive Early biomarker (DEBBIE), in which we will test the following hypotheses:

Methodological hypotheses:

- BBB-ASL can measure BBB permeability with high accuracy (as compared with PET)

- BBB-ASL permeability has high reproducibility for both healthy controls and patients

- Potential confounding physiological factors such as cerebral blood flow (CBF), arterial transit time (ATT), and atrophy, can be accounted for when quantifying BBB permeability

- BBB permeability has a specific range for each age category during healthy aging

- BBB-ASL permeability differs between healthy controls and AD patients

- BBB-ASL is associated with other (non-)imaging biomarkers of neurodegeneration and BBB

2. Methods

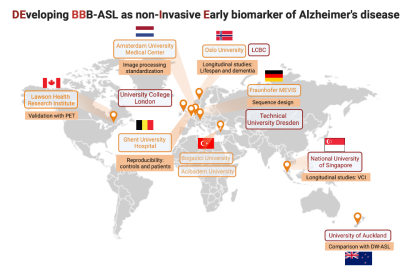

2.1. The DEBBIE consortiumThe collaborators of the DEBBIE consortium are shown in Figure 1. The individual partners will acquire BBB-ASL data using the protocol described below to contribute to the methodological and clinical goals.

2.2. MRI

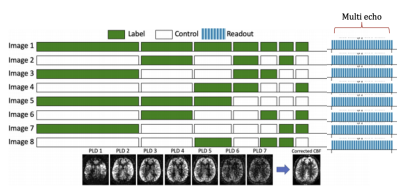

Our newly developed BBB-ASL sequence will be added to standard 3T clinical dementia MRI protocols, implemented with the vendor-independent MRI framework gammaSTAR(11). The BBB-ASL sequence combines time-encoded pseudo-continuous ASL with a multi-echo 2.5x2.5x5mm3 3D GRASE readout (Figure 2), allowing to estimate both CBF, ATT, and the BBB time of exchange (Tex)(12). For robust CBF, ATT, and Tex estimations, two ASL sequences will be acquired: one with 7 post-labeling delays (PLD) times (600:400:3400 ms, Hadamard 8 matrix) and a second with 3 PLD times (1500, 2500, 3500 ms; Hadamard 4 matrix) and 8 TEs (14.4:28.9:217.2 ms). M0 images will be acquired twice with reversed phase encoding for geometric distortion correction. Data from the two sequences will be analyzed in our ExploreASL pipeline(13,14), using a modified version of FSL FABBER(15) to quantify CBF, ATT, and Tex.

2.3. Participants

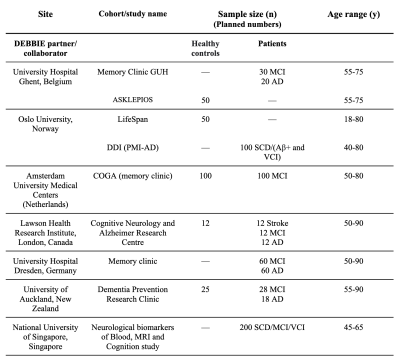

Participants 18 to 90 years of age will be recruited from the DEBBIE-associated cohorts (Table 1) including both cognitively normal subjects, defined as Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) score of 0 and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) ≥ 26) and participants with mild cognitive impairment (MCI; CDR = 0.5 and MMSE 23–26), or AD (MMSE < 23). Exclusion criteria include brain tumors, brain trauma, major psychiatric disorders, and neuropsychological testing exclusion criteria.

2.4. Biomarkers

In addition to MRI – which includes standard sequences such as T1w, T2w, FLAIR, DWI, and DTI – the DEBBIE clinical outcomes include amyloid-PET as well as blood and CSF fluid biomarkers (Table 1). The selection process for outcomes was based on evidence from available studies with an emphasis on the secondary prevention of AD.

2.5. Study design

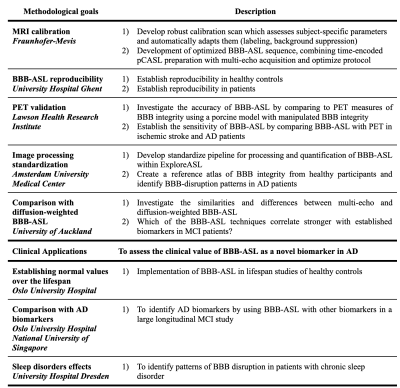

Individual sites will use the BBB-ASL protocol to test the hypotheses as described in Table 2. All data will be locally analysed with ExploreASL, and aggregated results will be used to develop BBB-ASL as an early AD biomarker.

3. Results

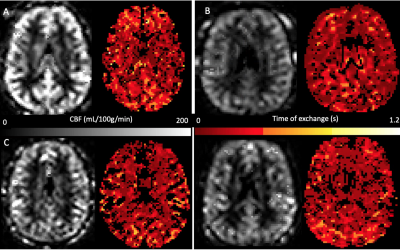

The study design process is currently being finalized before submitting applications to ethics committees in all institutes. The BBB-ASL sequence has been tested on 3T systems (different models by Siemens Heathineers, Erlangen, Germany) at multiple sites. Data processing was prepared in ExploreASL, including FSL-FABBER(15) for quantification. This allows standardized and consistent data processing at each site while respecting strict data protection regulations. Initial results have been collected from healthy volunteers at several sites, to show the feasibility of the multi-site BBB-ASL acquisition and data processing (Figure 3).4. Discussion

The major impacts of DEBBIE include 1) creating a consortium with both technical and clinical expertise, 2) providing empirical evidence on the use of BBB-ASL to measure the BBB permeability, and 3) demonstrating the utility of BBB-ASL in neurodegenerative diseases. The presented sequence may provide novel and unique insight into the staging of BBB disruption and potentially identify and differentiate AD-related pathologies in the early stages of development. In a healthy and intact BBB, water transport across the cell membrane has been shown to be restricted to the Aquaporin-4 channels, limiting the exchange rate (16).Acknowledgements

The DEBBIE project (Developing a non-invasive biomarker for early BBB breakdown in Alzheimer’s disease) is an EU Joint Programme -Neurodegenerative Disease Research (JPND) project. It is supported through the following funding organisations under the aegis of JPND -www.jpnd.eu (FWO in Belgium, Canadian Institutes of Health Research in Canada, BMBF in Germany, NFR in Norway, ZonMw and Alzheimer Nederland in The Netherlands, TÜBITAK in Turkey). The project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 825664.References

1. Montagne A, Nation DA, Sagare AP, et al. APOE4 leads to blood-brain barrier dysfunction predicting cognitive decline. Nature 2020;581:71–76.

2. Nation DA, Sweeney MD, Montagne A, et al. Blood-brain barrier breakdown is an early biomarker of human cognitive dysfunction. Nat. Med. 2019;25:270–276.

3. Serlin Y, Shelef I, Knyazer B, Friedman A. Anatomy and physiology of the blood-brain barrier. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2015;38:2–6.

4. Kalheim LF, Bjørnerud A, Fladby T, Vegge K, Selnes P. White matter hyperintensity microstructure in amyloid dysmetabolism. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2017;37:356–365.

5. Lee S, Viqar F, Zimmerman ME, et al. White matter hyperintensities are a core feature of Alzheimer’s disease: Evidence from the dominantly inherited Alzheimer network. Ann. Neurol. 2016;79:929–939.

6. Farrall AJ, Wardlaw JM. Blood-brain barrier: ageing and microvascular disease--systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurobiol. Aging 2009;30:337–352.

7. Starr JM, Farrall AJ, Armitage P, McGurn B, Wardlaw J. Blood-brain barrier permeability in Alzheimer’s disease: a case-control MRI study. Psychiatry Res. 2009;171:232–241.

8. Keaney J, Campbell M. The dynamic blood-brain barrier. FEBS J. 2015;282:4067–4079.

9. Weller RO, Subash M, Preston SD, Mazanti I, Carare RO. Perivascular Drainage of Amyloid-b Peptides from the Brain and Its Failure in Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy and Alzheimer’s Disease. Brain Pathol. 2008;18:253–266.

10. Gregori J, Schuff N, Kern R, Günther M. T2-based arterial spin labeling measurements of blood to tissue water transfer in human brain. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2013;37:332–342.

11. Cordes C, Konstandin S, Porter D, Günther M. Portable and platform-independent MR pulse sequence programs. Magn. Reson. Med. 2020;83:1277–1290.

12. Mahroo A, Buck MA, Huber J, et al. Robust Multi-TE ASL-Based Blood-Brain Barrier Integrity Measurements. Front. Neurosci. 2021;15:719676.

13. Mutsaerts HJMM, Petr J, Groot P, et al. ExploreASL: An image processing pipeline for multi-center ASL perfusion MRI studies. Neuroimage 2020;219:117031.

14. Clement P, Petr J, Dijsselhof MBJ, et al. A Beginner’s Guide to Arterial Spin Labeling (ASL) Image Processing. Frontiers in Radiology 2022;2 doi: 10.3389/fradi.2022.929533.

15. Chappell MA, Groves AR, Whitcher B, Woolrich MW. Variational Bayesian Inference for a Nonlinear Forward Model. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2009;57:223–236.

16. Bonomini F, Rezzani R. Aquaporin and blood brain barrier. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2010;8:92–96.

Figures