0366

3D MR Fingerprinting with Fat-navigator-based Motion Correction for Pediatric Imaging1Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Motion Correction, MR Fingerprinting

MR Fingerprinting (MRF) simultaneously measures multiple tissue properties within a single scan. Although 2D MRF has been shown to be less sensitivie to motion than conventional imaging, bulk motion is still problematic for longer 3D MR Fingerprinting scans. We propose to integrate 3D fat navigators with 3D MRF acquisitions for motion correction in neuroimaging, especially for non-sedated pediatric imaging. The proposed method was validated in in vivo scans of healthy subjects with various types of motions and in non-sedated infants. We showed that the fat-navigated 3D MRF framework could resolve and correct bulk motions of both healthy volunteers and infants.Introduction

MR Fingerprinting (MRF) simultaneously measures multiple tissue properties within a single scan1. MRF scans are known to yield better robustness against subject motion as compared to conventional MRI, since the inherently motion-insensitive spiral trajectories are often utilized, and the dictionary matching process could further reduce motion artifacts1,2. However, 3D MRF scans are susceptible to bulk motions due to the long scan time. 3D fat-navigator-based motion correction has been developed in previous studies for structural brain imaging3,4. Here, we propose to implement a 3D fat-navigator-based motion correction algorithm with high-image-resolution 3D MRF scans to improve motion robustness. We show that the proposed approach could monitor and correct the motions of healthy volunteers and non-sedated infants with neonatal opioid withdrawal symptoms.Methods

AcquisitionTo improve the motion robustness of 3D MRF scans, a 3D fat navigator module was inserted during the wait time at the end of each partition acquisition as described in (5). The FLASH-based fat navigators were acquired with spiral GRAPPA along both in-plane and through-plane directions with acceleration factors of R6x25. The imaging parameters for the 3D fat navigator: FOV, 250x250x144mm3; image resolution 2x2x3mm3; flip angle, 6 degrees; scan time, ~0.5 sec.

3D MRF data were acquired using FISP-MRF sequences adapted from (6). All scans were acquired on a 3T Siemens Vida scanner. The acquisition parameters for 3D MRF: 1mm3 isotropic resolution, scan time ~5.6 min for whole-brain coverage.

Reconstruction

Each fat navigator image volume was reconstructed with a 3x2 GRAPPA kernel in both in-plane and through-plane directions. Motion waveforms were then extracted from the reconstructed fat image series using the SPM12 toolbox. Motions were corrected in k-space of the 3D MRF data, which was subsequently processed by iterative reconstruction with SVD-based dictionary compression7,8.

Validation

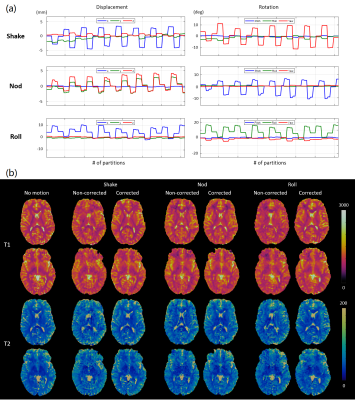

We first performed simulations to evaluate the effect of various motions on the MRF maps before and after motion correction. Sinusoidal motion waveforms of in-plane/through-plane rotation and translation were simulated respectively (Figure 1a). The simulated rotational motions were within ±10 degrees, and the translation motions were within ±5mm to match the extent of motions observed in in vivo scans (Figure 2a). The motions were applied to a 3D digital brain phantom in the image domain; the data was undersampled according to the actual 3D MRF scheme and the motion was corrected in k-space.

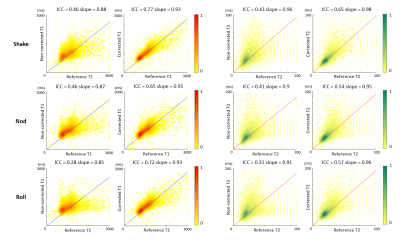

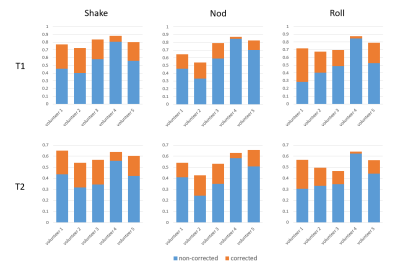

The proposed fat-navigated 3D MRF scan was tested on 5 healthy subjects. All subjects were scanned with a reference MRF scan with no motion and 3 MRF scans with 3 types of motions. The subjects were instructed to continuously perform shaking, nodding, and rolling throughout the acquisitions in 3 separate scans. The motion-corrected and non-corrected MRF maps were compared against the reference MRF dataset. Specifically, the MRF maps from the motion scans and the reference scan were co-registered after skull stripping, followed by pixel-wise comparisons of T1 and T2 values of the center slice. The Intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) was calculated to evaluate the similarity between each pair.

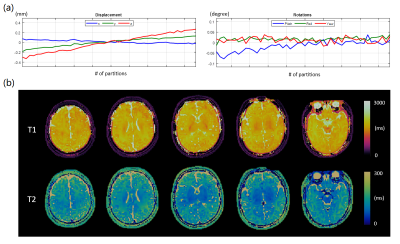

The proposed approach was also implemented for the OBOE (Outcomes of Babies with Opioid Exposure) study. A non-sedated 1-month-old infant exhibiting neonatal opioid withdrawal symptoms was scanned with the fat-navigated 3D MRF protocol.

Results

Figure 1 shows the simulated T1 and T2 maps before and after motion correction using the four types of simulated motions. Rotations mainly cause blurring of sharp edges, and translations lead to blurring and ghosting artifacts without motion corrections, resulting in root-mean-square errors of up to 35.5% for T1 and 42.8% for T2. These errors are significantly reduced to 5.9%, 7.7%, 5.8%, and 5.6% for T1; 9.4%, 11.8%, 9.2%, and 8.7% for T2 after correction.Figure 2 shows in vivo MRF maps acquired on a representative volunteer. The motions caused severe blurring and ghosting artifacts similar to those observed in simulations before motion correction. Motion-corrected MRF maps were robust against such artifacts.

Figure 3 shows the results of pixel-wise quantitative comparisons between the MRF maps from the motion scans and the reference scans. The ICC of non-corrected MRF maps versus the reference were all below 0.5 for both T1 and T2, indicating poor reliability. Motion corrections significantly raised ICC to 0.77, 0.65, and 0.72 for T1, showing excellent correlations with the reference; the ICC of T2 of 0.65, 0.54, and 0.57 were slightly lower, yet yield good correlations. Results of the pixel-wise analysis for all five volunteers (Figure 4) demonstrate consistent improvements in ICC for both T1 and T2 after motion correction in all cases.

Figure 5 shows the motion-corrected results of an infant with opioid exposure. While the subject was scanned during natural sleep, bulk shifting motion was detected during the acquisition. The corrected MRF scans could reveal brain structures with unique contrast between white matter and grey matter.

Conclusions

We propose a motion-corrected MRF framework using fat navigators to effectively reduce motion-related artifacts for neuroimaging. The proposed approach could be combined with an accelerated high-resolution 3D MRF framework, and significantly improves its robustness against various types of head motions. We also demonstrate a promising application of the method for a non-sedated baby with neonatal opioid withdrawal symptoms from our OBOE study. Future studies will be continued for extensive pediatric populations.Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge funding from Siemens Healthineers and NIH grants EB026764-01 and NS109439-01.References

1. Ma D, Gulani V, Seiberlich N, et al. Magnetic Resonance Fingerprinting. Nature. 2013;495(7440):187-192.

2. Gao Y, Chen Y, Ma D, et al. Preclinical MR fingerprinting (MRF) at 7 T: effective quantitative imaging for rodent disease models. NMR Biomed. 2015;28(3):384-394. doi:10.1002/nbm.3262

3. Gallichan D, Marques JP, Gruetter R. Retrospective correction of involuntary microscopic head movement using highly accelerated fat image navigators (3D FatNavs) at 7T. Magn Reson Med. 2016;75(3):1030-1039. doi:10.1002/mrm.25670

4. Gallichan D, Marques JP. Optimizing the acceleration and resolution of three-dimensional fat image navigators for high-resolution motion correction at 7T. Magn Reson Med. 2017;77(2):547-558. doi:10.1002/mrm.26127

5. Chen Y, Zong X, Ma D, Lin W, Griswold M. Improving motion robustness of 3D MR Fingerprinting using fat navigator. 29th Proc Intl Soc Mag Reson Med. Published online 2020.

6. Jordan SP, Hu S, Rozada I, et al. Automated design of pulse sequences for magnetic resonance fingerprinting using physics-inspired optimization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(40). doi:10.1073/PNAS.2020516118/-/DCSUPPLEMENTAL

7. McGivney DF, Pierre E, Ma D, et al. SVD compression for magnetic resonance fingerprinting in the time domain. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2014;33(12):2311-2322. doi:10.1109/TMI.2014.2337321

8. Hamilton JI, Jiang Y, Ma D, et al. Simultaneous multislice cardiac magnetic resonance fingerprinting using low rank reconstruction. NMR Biomed. 2019;32(2):e4041. doi:10.1002/NBM.4041

Figures