0365

Evaluation of Scout Accelerated Motion Estimation and Reduction (SAMER) MPRAGE for Visual Grading and Volumetric Measurement of Brain Tissue1Radiology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, United States, 2Siemens Medical Solutions USA, Boston, MA, United States, 3Siemens Healthcare GmbH, Erlangen, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: Motion Correction, Neurodegeneration

Volumetric brain MRI using the T1-weighted-MPRAGE sequence is an important component of the clinical evaluation of dementia. However, MPRAGE has a long acquisition time and is especially prone to patient motion artifact. A recent development to address this issue is a technique called Scout Accelerated Motion Estimation and Reduction (SAMER). In this work, we used a set of 90 MPRAGE scans derived from 10 healthy volunteers to demonstrate that SAMER is effective at correcting various degrees of motion, including severe motion with non-diagnostic image quality, and greatly increases the accuracy of volumetric brain measurements.Introduction

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is limited in practice by patient motion artifacts, which can result in costly non-diagnostic scans [1-4]. One of the most motion-prone exams is volumetric brain MRI, which quantifies characteristics such as cortical volume and thickness and can help diagnose neurodegenerative diseases [5]. Specifically, the 3D-T1-weighted-MPRAGE sequence is a standard part of MRI protocols to evaluate memory loss and serves as the basis for volumetric measurements; nevertheless, it is especially prone to long acquisition times and motion artifact [6].One approach to shorten acquisition time of the MPRAGE sequence uses a novel technique called Wave Controlled Aliasing in Parallel Imaging (Wave-CAIPI) [7]. Wave-CAIPI-accelerated MPRAGE has been validated clinically against standard MPRAGE and shown to equivalently assess cortical volume and thickness [8]. Subsequently, a complementary approach, Scout-Accelerated Motion Estimation and Correction (SAMER) was developed to reduce motion artifact [9, 10], and is currently undergoing clinical evaluation.

Preliminary work on one volunteer suggested that SAMER-MPRAGE successfully corrected mild motion artifact and resulted in cortical volume and thickness estimates comparable to those obtained with standard MPRAGE [11]. In this study, we used 90 MRI scans derived from ten volunteers to show that SAMER can correct motion-induced errors even in the most motion-prone regions of the brain and facilitate accurate volumetric analysis.

Methods

Ten volunteers underwent five different in vivo MPRAGE scans at R=4-fold acceleration. The first was a Wave-CAIPI-MPRAGE sequence which was considered the reference standard, while the remaining four corresponded to acquisitions performed with SAMER-MPRAGE with varying degrees of motion corruption: “no”, “mild”, “moderate”, and “severe” motion [1]. Motion-corrupted scans underwent motion correction with SAMER. In total, each volunteer generated nine scans: Wave-CAIPI-MPRAGE and SAMER-MPRAGE, pre- and post-motion correction for each motion state, resulting in 90 effective total number of MRI scans analyzed.All scans were acquired on a 3T system (MAGNETOM Skyra, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) using a 20-channel head coil. The sequence parameters used were: FOV 256x256x192mm; matrix 256x256x192; TR/TE/TI 2300/3.2 (3.3 for SAMER)/1000ms; flip angles 8°; bandwidth 200 Hz/Px; acquisition times 2:39 min. Each volunteer was instructed to perform varying degrees of deep breathing during the motion scans, something known to introduce motion artifact. Motion estimation and image reconstruction were performed with an online reconstruction directly on the scanner and generated additional motion-corrected images.

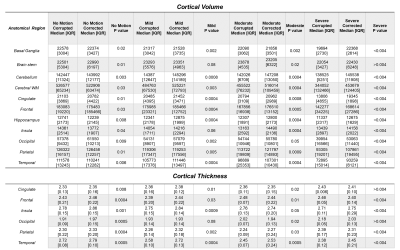

For the nine sets of images from each volunteer, Freesurfer [12] calculated cortical volume for 11 brain regions (frontal, parietal, temporal, occipital lobes, cingulate gyrus, insula, hippocampus, basal ganglia, brain stem, cerebellum, cerebral white matter (WM)) and thickness for 6 brain regions (frontal, parietal, temporal, occipital lobes, cingulate gyrus, insula). Cortical volumes and thicknesses for each region were averaged across all volunteers. Percent-error for the averaged cortical volume and thickness was calculated, treating Wave-CAIPI-MPRAGE results as the reference standard:

$$100*\frac{\left|AveragedVolumeOrThickness - Reference\right|}{Reference}$$

The statistical significance of each SAMER motion correction was assessed using paired Wilcoxon rank sum tests comparing the cortical thickness and volume across each anatomical region for uncorrected versus corrected scans.

Results and Discussion

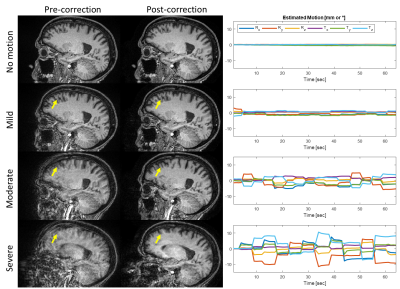

Freesurfer completed cortical volume and thickness calculations on 84/90 (~93%) scans; the 6 calculations that failed were mostly due to severe motion artifact before motion correction, and 5/6 of these were successfully completed in the corresponding SAMER-corrected scans. Representative cases illustrate the effect of various degrees of motion and subsequent correction with SAMER (Figure 1), as well as the corresponding Freesurfer segmentation (Figure 2).Errors introduced by motion artifact resulted in Freesurfer generally underestimating the reference volume (Figures 2/3A) in a manner directly proportional with the degree of motion, consistent with prior reported associations [13]. The most affected anatomical areas appear to be the temporal lobe (Figure 2) and the cerebral white matter, with percent error values on severe motion scans reaching 38% and 32%, respectively (Figure 3B). At the same time, SAMER considerably reduced the volume calculation error across all anatomical areas; for example, the percent error values corresponding to the temporal lobe and cerebral white matter were 19% and 10%, respectively.

Estimates of the cortical thickness behaved similarly to the ones for volume in that the temporal lobe is the most affected (Figure 4A). However, the magnitude of the percent error is generally less across the examined anatomical areas (Figure 4B), with the highest value for the severe motion scans being 15% for the temporal lobe. SAMER’s contributions to the accuracy of thickness estimates are more modest. For example, the temporal lobe percent error was reduced to 11%. There were also areas that showed no significant correction, such as the insula. Interestingly, the largest relative reduction in error with SAMER occurred in the occipital lobe (11% to 4%), where severe motion resulted in overestimation of the cortical thickness, in contrast to the remainder of the anatomical areas. Overall, SAMER results in statistically significant improvements in calculated cortical volume and thickness between uncorrected and corrected scans across most anatomical regions (Figure 5).

Conclusion

SAMER corrects for severe motion artifact and can turn non-diagnostic-quality scans into ones that allow for accurate computation of cortical volume and thickness. Our results suggest that SAMER has strong potential for evaluation in practical clinical settings and can contribute to diagnosing dementia and neurodegenerative disease.Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by NIH research grants P41EB030006-01, 5U01EB025121-03 and a research grant from Siemens Healthineers.

References

[1] Andre JB, Bresnahan BW, Mossa-Basha M, Hoff MN, Smith CP, Anzai Y, et al. Toward Quantifying the Prevalence, Severity, and Cost Associated With Patient Motion During Clinical MR Examinations. J Am Coll Radiol. 2015;12:689-95.

[2] Munn Z, Pearson A, Jordan Z, Murphy F, Pilkington D, Anderson A. Patient Anxiety and Satisfaction in a Magnetic Resonance Imaging Department: Initial Results from an Action Research Study. J Med Imaging Radiat Sci. 2015;46:23-9.

[3] Havsteen I, Ohlhues A, Madsen KH, Nybing JD, Christensen H, Christensen A. Are Movement Artifacts in Magnetic Resonance Imaging a Real Problem?-A Narrative Review. Front Neurol. 2017;8:232.

[4] Slipsager JM, Glimberg SL, Sogaard J, Paulsen RR, Johannesen HH, Martens PC, et al. Quantifying the Financial Savings of Motion Correction in Brain MRI: A Model-Based Estimate of the Costs Arising From Patient Head Motion and Potential Savings From Implementation of Motion Correction. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2020;52:731-8.

[5] Lehmann M, Douiri A, Kim LG, Modat M, Chan D, Ourselin S, et al. Atrophy patterns in Alzheimer's disease and semantic dementia: a comparison of FreeSurfer and manual volumetric measurements. Neuroimage. 2010;49:2264-74.

[6] Mugler JP, 3rd, Brookeman JR. Rapid three-dimensional T1-weighted MR imaging with the MP-RAGE sequence. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1991;1:561-7.

[7] Polak D, Setsompop K, Cauley SF, Gagoski BA, Bhat H, Maier F, et al. Wave-CAIPI for highly accelerated MP-RAGE imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2018;79:401-6.

[8] Longo MGF, Conklin J, Cauley SF, Setsompop K, Tian Q, Polak D, et al. Evaluation of Ultrafast Wave-CAIPI MPRAGE for Visual Grading and Automated Measurement of Brain Tissue Volume. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2020;41:1388-96.

[9] Polak D, Splitthoff DN, Clifford B, Lo WC, Huang SY, Conklin J, et al. Scout accelerated motion estimation and reduction (SAMER). Magn Reson Med. 2022;87:163-78.

[10] Polak D, Hossbach J, Splitthoff DN, Clifford B, Lo WC, Tabari A, et al. Motion guidance lines for robust data-consistency based retrospective motion correction in 2D and 3D MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2023. doi:10.1002/mrm.29534

[11] Lo WC, Conklin J, Clifford B, Tian Q, Polak D, Splitthoff D, et al. Evaluation of Scout Accelerated Motion Estimation and Reduction (SAMER) for measuring brain volume and cortical thickness. International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. London, England, United Kingdom 2022.

[12] Fischl B. FreeSurfer. Neuroimage. 2012;62:774-81.

[13] Reuter M, Tisdall MD, Qureshi A, Buckner RL, van der Kouwe AJW, Fischl B. Head motion during MRI acquisition reduces gray matter volume and thickness estimates. Neuroimage. 2015;107:107-15.

Figures