0364

Detecting bladder and pelvic floor motion during MRI using a small ultrasound-based sensor1Center for Advanced Imaging Innovation and Research, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY, United States, 2Siemens Medical Solutions USA, New York, NY, United States, 3NYU Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY, United States, 4Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Motion Correction, Hybrid & Novel Systems Technology

Deep-seated motion due to digestion and bladder filling can be difficult to monitor during MR acquisition. In this study, we use a small ultrasound-based sensor to detect bladder and pelvic floor motion, with a real-time MRI acquisition and a pilot-tone motion-sensitive signal as a reference. A neural network is used to predict the bladder area at various times during the MRI scan by using the US signal features. Our results indicate that the correlations between the ultrasound sensor and the MRI are beneficial for detecting bladder motion over time.Introduction

Motion detection/correction remains a challenge in abdominal imaging, where organs move due to breathing, digestion or bladder filling1. To monitor breathing or bulk motion, devices/methods such as navigator echoes, the pilot-tone or optical trackers have proved effective 2,3, however, subtler/deeper-seated motion such as bladder filling is harder to detect. While many motion-monitoring devices are only sensitive to body contours, here we use an ultrasound (US)-based sensor that can detect changes deep inside the body. This type of sensor was previously used for respiration monitoring4, but it is used here for organ monitoring. Specifically, its ability to detect changes in bladder shape/size and pelvic floor contraction was tested here, against a real-time MRI reference and pilot tone signals.Methods

Data Acquisition4 female volunteers were recruited following an informed consent with an IRB-approved protocol. Free-breathing lower abdomen images were acquired at a rate of ~18 frames/s (Aera 1.5T system modified to operate at 0.55T, 2D radial bSSFP, single slice, 2.3mm thick, TR=2.26ms, TE = 1.13m). Concurrent pilot tone (23.81 MHz) and A-mode ultrasound data (221 firings/s) was acquired by placing a single-element, US transducer ~3 inches directly below the navel on each subject. The sensor was coated with US gel and adhered to the subject using adhesive bandage, and fired in synchrony with the MR RF pulses. The volunteer was instructed to occasionally tighten their pelvic floor muscles to test the ability of the sensor to detect such motion.

MRI Processing

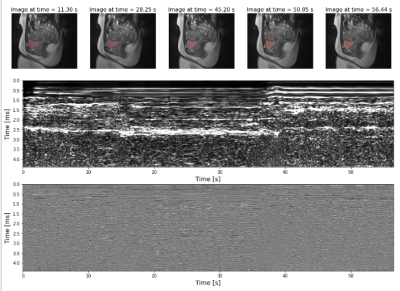

The dynamic bSSFP data was reconstructed using a sliding window algorithm to generate the time point images with a 17.69sec temporal resolution. Otsu’s method and 3D connected component analysis was used to threshold the reconstructed image to segment the bladder and calculate its area throughout the acquisition.

US Processing

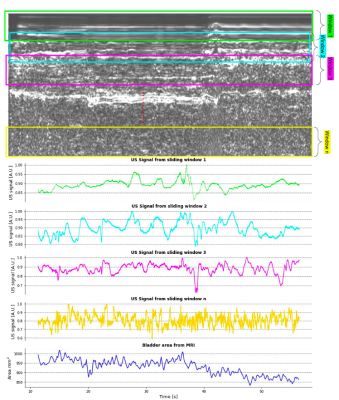

The US signal was reconstructed as a complex 2D signal, where the vertical axis is a surrogate for depth through the body and the horizontal axis is time through the scan. A sliding window approach was used through the depth dimension in order to extract a spatially weighted mean signal which would serve as a ‘feature map’ for each depth (Figure 1).

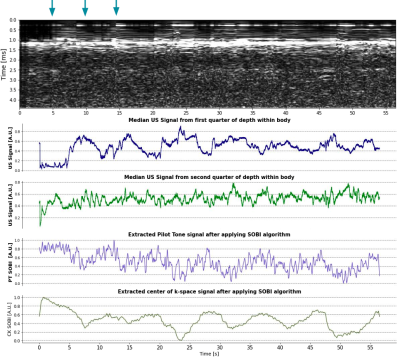

Pilot Tone and Center of K-Space Signal Extraction

The PilotTone (PT) signal was detected and separated from the raw MRI data using a peak detection algorithm in the frequency domain. The center-of-k-space (CK) signal was extracted by averaging the center 3 points in k-space along each radial readout. For consistency among all experiments, the Second Order Blind Identification (SOBI) algorithm was applied to the PT and CK signals encoded by a selected receive coil to isolate respiratory motion6.

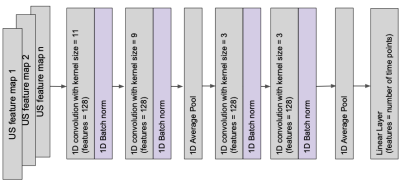

Neural Network to Predict Bladder Area

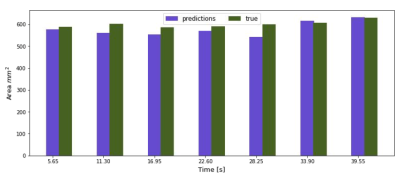

A 1-D convolutional neural network (Figure 5) was trained on 3 subjects to see if the extracted US ‘feature maps’ can predict the bladder area during acquisition on the unseen test subject ~every 5 s. The network was trained with an AdamW optimizer (LR = 0.0001, WD = 0.0005) and a L1 loss function. The feature maps were fed into the channel dimension of the network. Early stopping and dropout was used to combat overfitting.

Results

Figure 2 shows an example of the fast in-house bSSFP sequence along with the simultaneously acquired US data. Changes in bladder shape can be appreciated between times 28.25 s and 45.20 s on the automatic bladder segmentation. Figure 3 shows the comparison of the US sensor signal with other surrogate signals. While the PT and CK curve show modulations due to movement and breathing, it is not possible to appreciate the differences caused due to the squeezing as seen in the US ~every 5 s.Figure 5 shows the bladder areas predicted by the network and those in the ground truth mask.The mean absolute error of the prediction is 25.45 mm2 and the Pearson correlation coefficient between the predicted and the growth truth values is 0.78 (p = 0.03).

Discussion

Our results show that the ultrasound sensor has rich spatial information as compared to the pilot tone that could be used for applications beyond motion correction. Preiswerk et al train models on each patient to predict on the same patient, showing that there are correlations between the US and MR signals that can allow the US to act as surrogate for the MR6. In our preliminary study, we used that correlation to train sensors to predict a specific anatomical marker on a different patient than the model was trained on. With more generalizable models adapted to multiple organs, this study suggests that sensor signals could help in the live monitoring of organs even while outside of the MRI scanner, a functionality that would prove impossible with other devices such as the pilot tone that function only in the MRI environment.The main limitation of our study is the small cohort size which is insufficient to train a more generalizable model, which we will address by acquiring a larger sample size with longer acquisitions.

Conclusion

Correlations between ultrasound and MRI signals can be exploited to predict anatomical changes over time.Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Radiology Department at NYU Grossman School of Medicine (Center for Advanced Imaging Innovation and Research)References

1. Bertholet, Jenny, et al. "Real-time intrafraction motion monitoring in external beam radiotherapy." Physics in Medicine & Biology 64.15 (2019): 15TR01.

2. Vahle, Thomas, et al. "Respiratory motion detection and correction for MR using the pilot tone: applications for MR and simultaneous PET/MR exams." Investigative radiology 55.3 (2020): 153.

3. Madore, Bruno, et al. "Ultrasound-based sensors for respiratory motion assessment in multimodality PET imaging." Physics in Medicine & Biology 67.2 (2022): 02NT01.

4. Madore, Bruno, et al. "Ultrasound‐based sensors to monitor physiological motion." Medical Physics 48.7 (2021): 3614-3622.

5. Solomon, Eddy, et al. "Free‐breathing radial imaging using a pilot‐tone radiofrequency transmitter for detection of respiratory motion." Magnetic resonance in medicine 85.5 (2021): 2672-2685.

6. Preiswerk, Frank, et al. "Hybrid MRI‐Ultrasound acquisitions, and scannerless real‐time imaging." Magnetic resonance in medicine 78.3 (2017): 897-908.

Figures