0344

Time-dependent Diffusion in the Human Heart In Vivo1Leeds Institute of Cardiovascular and Metabolic Medicine, University of Leeds, Leeds, United Kingdom, 2Medical Radiation Physics, Clinical Sciences Lund, Lund University, Lund, Sweden, 3Danish Research Centre for Magnetic Resonance, Centre for Functional and Diagnostic Imaging and Research, Copenhagen University Hospital Amager and Hvidovre, Copenhagen, Denmark, 4Random Walk Imaging, Lund, Sweden, 5Leeds Teaching Hospitals Trust, Leeds, United Kingdom, 6Cardiff University Brain Research Imaging Centre (CUBRIC), School of Psychology, Cardiff University, Cardiff, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: Myocardium, Diffusion Tensor Imaging, Time dependence, microstructure, motion compensation

Conventional spin-echo based cardiac diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) has a relatively limited range of encoding frequencies, and hence limited sensitivity to diffusion at different length scales. Here, we explored the feasibility of applying a broader range of frequencies to evaluate the effects of time-dependent diffusion. We employed diffusion encoding waveforms with up to 4th order motion-compensation in a cohort of healthy volunteers, and report trends of decreasing MD and FA with increasing encoding frequencies. The availability of higher frequencies enhances the sensitivity of DTI to shorter length scales, and may be more greatly weighted towards diffusion properties of sub-cellular structures.Introduction

Cardiac diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) is fast gaining traction as a unique means for myocardial tissue characterisation, without use of contrast agents. It has been used to characterise microstructural changes in health and disease, e.g. hypertrophic1-3 and dilated cardiomyopathy4, infarction5 and amyloidosis6. Mean diffusivity (MD) and fractional anisotropy (FA) are sensitive to a range of biophysical properties. However, they are also known to be sensitive to imaging parameters, including diffusion time (td)7.Early work in ex vivo hearts used a long diffusion time stimulated echo approach. In calf heart, the 2nd and 3rd diffusion eigenvalues were seen to decrease as td increased, reflecting the known anisotropic cardiomyocyte geometry8. In pig heart, mean displacement increased as a function of td9. In other work based on oscillating gradient spin echo (OGSE), time-dependent diffusion (TDD) was evaluated in mouse heart at much higher frequencies up to 250 Hz10. The results suggested that there was anisotropy at much shorter length scales, that may be associated with intracellular organelles. In mouse and pig heart, TDD in MD was observed using tensor-valued encoding11. Examining TDD in vivo is more challenging due to cardiac and respiratory motion. In initial work, we employed tensor-valued encoding with 2nd order motion compensation, and observed that MD was higher in spherical tensor encoding compared to linear tensor encoding, consistent with the greater encoding power at lower frequencies in the latter7.

In this work, we evaluate TDD in the human heart in vivo and extend the range of encoding frequencies. In doing so, we report novel application of diffusion encoding waveforms with up to 4th-order motion-compensation.

Methods

Data were acquired in healthy volunteers (N = 6) on a Prisma 3T MRI scanner (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany). Volunteers provided written consent, and the study was performed under approved ethics. DTI data were acquired with a prototype single-shot spin-echo sequence with EPI-readout and Zoom-IT for reduced FOV imaging12. Subjects were scanned free-breathing and with cardiac-triggering. Parameters were TR = 3 RR-intervals, TE = 128 ms, resolution = 3×3×8 mm3, 3 slices, field-of-view = 320×111 mm2, blow = 50 s/mm2 with 3 orthogonal directions, bhigh = 300 s/mm2 with 30 orthogonal directions13, diffusion encoding directions were mirrored for full-sphere coverage, acquisition time per waveform ~4.2 min based on 60 beats per minute. Four diffusion encoding waveforms were employed: M2 2-lobes (bipolar), M2 3-lobes, M3 4-lobes and M4 5-lobes, where Mn describes motion-compensation up to nth order, and lobes refers to the number of lobes within each pre- and post-180 waveform. The waveforms were characterised by the mean frequency14 (in Hz) of the power spectrum of the dephasing vector q(t). The first waveform was adapted from Welsh et al15, and the latter three were derived from Lasič et al11, 16. All images were rigidly registered to a common reference image, and outliers were rejected. Images were manually segmented and sub-divided into 16 AHA segments. Parameter maps are reported in the septal wall of a mid-myocardial short-axis slice in the left ventricle, corresponding to AHA segments 8 & 9.Results

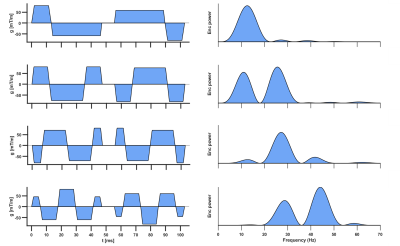

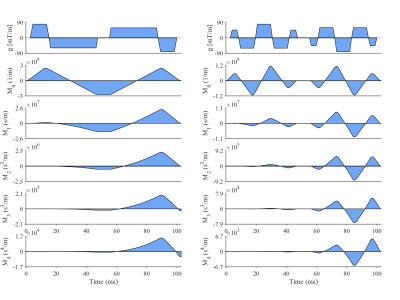

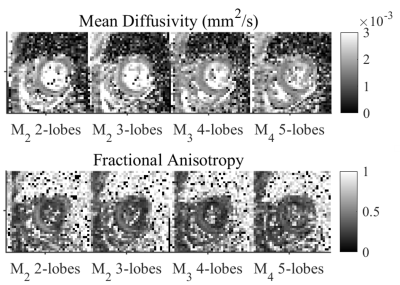

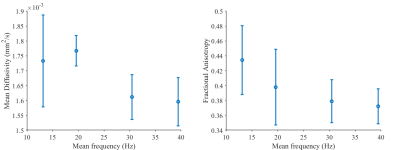

Figure 1 shows the diffusion encoding waveforms and corresponding encoding power spectra. The power spectra were either predominantly unimodal or bimodal. Figure 2 illustrates motion-compensation (also gradient moment nulling) from 0th up to 4th order. Representative maps of MD and FA in one healthy volunteer are shown (Figure 3). The MD and FA were plotted as a function of mean frequency (Figure 4; mean ± SD across subjects). MD and FA decreased by 8% and 14% respectively as mean frequency increased from 13 to 39 Hz.Discussion

Our findings recapitulate ex vivo findings, insofar as a higher encoding frequency leads to lower FA. However, a counterintuitive trend towards lower MD was observed at higher frequencies. One consideration is that the MD using the conventional M2 bipolar waveform was 10-20% higher than in other studies3, 17, which may be indicative of the poorer motion compensation over the longer diffusion encoding waveforms used here. The lower MD at higher frequencies may then be partially attributed to the improved 3rd and/or 4th order motion-compensation relative to the M2 bipolar waveform.Limitations include the use of variable degrees of motion compensation which may confound contributions from TDD. A longer minimum TE leads to lower SNR, resolution and b-value compared to conventional cardiac DTI. As encoding frequencies increase, b-value efficiency decreases, and this work would benefit from higher performance gradients. Finally, we considered the nominal diffusion encoding gradients, and background and imaging gradients were ignored.

Conclusion

We have demonstrated TDD in the human heart in vivo over a wider range of frequencies than before, and demonstrated proof-of-concept application of 4th order motion-compensated DTI. Better understanding of the sensitivity of DTI to TDD will contribute to improved waveform design, help disentangle TDD from microanisotropy11, provide additional sensitivity to shorter length scales of diffusion, and may enhance the prospect of obtaining biophysical measurements of the myocardium in vivo based on compartmental modelling18.Acknowledgements

We thank Siemens Healthcare for the pulse sequence development environment. This work was supported by the British Heart Foundation, UK (PG/19/1/34076, CH/16/2/32089). JES acknowledges funding from the Wellcome Trust 219536/Z/19/Z. SL and HL have received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No 804746).References

1. Das A, Chowdhary A, Kelly C, Teh I, Stoeck CT, Kozerke S, Maxwell N, Craven TP, Jex NJ, Saunderson CED, Brown LAE, Ben-Arzi H, Sengupta A, Page SP, Swoboda PP, Greenwood JP, Schneider JE, Plein S and Dall'Armellina E. Insight Into Myocardial Microstructure of Athletes and Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Patients Using Diffusion Tensor Imaging. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging : JMRI. 2020.

2. Ariga R, Tunnicliffe EM, Manohar SG, Mahmod M, Raman B, Piechnik SK, Francis JM, Robson MD, Neubauer S and Watkins H. Identification of Myocardial Disarray in Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy and Ventricular Arrhythmias. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:2493-2502.

3. Das A, Kelly C, Teh I, Nguyen C, Brown LAE, Chowdhary A, Jex N, Thirunavukarasu S, Sharrack N, Gorecka M, Swoboda PP, Greenwood JP, Kellman P, Moon JC, Davies RH, Lopes LR, Joy G, Plein S, Schneider JE and Dall'Armellina E. Phenotyping hypertrophic cardiomyopathy using cardiac diffusion magnetic resonance imaging: the relationship between microvascular dysfunction and microstructural changes. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022;23:352-362.

4. Nielles-Vallespin S, Khalique Z, Ferreira PF, de Silva R, Scott AD, Kilner P, McGill LA, Giannakidis A, Gatehouse PD, Ennis D, Aliotta E, Al-Khalil M, Kellman P, Mazilu D, Balaban RS, Firmin DN, Arai AE and Pennell DJ. Assessment of Myocardial Microstructural Dynamics by In Vivo Diffusion Tensor Cardiac Magnetic Resonance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:661-676.

5. Das A, Kelly C, Teh I, Stoeck CT, Kozerke S, Chowdhary A, Brown LAE, Saunderson CED, Craven TP, Chew PG, Jex N, Swoboda PP, Levelt E, Greenwood JP, Schneider JE, Plein S and Dall'Armellina E. Acute Microstructural Changes after ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction Assessed with Diffusion Tensor Imaging. Radiology. 2021;299:86-96.

6. Gotschy A, von Deuster C, van Gorkum RJH, Gastl M, Vintschger E, Schwotzer R, Flammer AJ, Manka R, Stoeck CT and Kozerke S. Characterizing cardiac involvement in amyloidosis using cardiovascular magnetic resonance diffusion tensor imaging. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2019;21:56.

7. Lasic S, Szczepankiewicz F, Dall'Armellina E, Das A, Kelly C, Plein S, Schneider JE, Nilsson M and Teh I. Motion-compensated b-tensor encoding for in vivo cardiac diffusion-weighted imaging. NMR in biomedicine. 2020;33:e4213.

8. Kim S, Chi-Fishman G, Barnett AS and Pierpaoli C. Dependence on diffusion time of apparent diffusion tensor of ex vivo calf tongue and heart. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2005;54:1387-96.

9. Froeling M, Mazzoli V, Nederveen AJ, Luijten PR and Strijkers GJ. Ex vivo cardiac DTI: on the effects of diffusion time and b-value. Journal of cardiovascular magnetic resonance : official journal of the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. 2014;16 (Suppl 1):P77.

10. Teh I, Schneider JE, Whittington HJ, Dyrby TB and Lundell H. Temporal Diffusion Spectroscopy in the Heart with Oscillatiing Gradients. Proc Int Soc Magn Reson Med. 2017:3114.

11. Lasič S, Yuldasheva N, Szczepankiewicz F, Nilsson M, Budde M, Dall’Armellina E, Schneider JE, Teh I and Lundell H. Stay on the Beat With Tensor-Valued Encoding: Time-Dependent Diffusion and Cell Size Estimation in ex vivo Heart. Frontiers in Physics. 2022;10.

12. Szczepankiewicz F, Sjolund J, Stahlberg F, Latt J and Nilsson M. Tensor-valued diffusion encoding for diffusional variance decomposition (DIVIDE): Technical feasibility in clinical MRI systems. PloS one. 2019;14:e0214238.

13. Jones DK, Horsfield MA and Simmons A. Optimal strategies for measuring diffusion in anisotropic systems by magnetic resonance imaging. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1999;42:515-25.

14. Arbabi A, Kai J, Khan AR and Baron CA. Diffusion dispersion imaging: Mapping oscillating gradient spin-echo frequency dependence in the human brain. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2020;83:2197-2208.

15. Welsh CL, DiBella EV and Hsu EW. Higher-Order Motion-Compensation for In Vivo Cardiac Diffusion Tensor Imaging in Rats. IEEE transactions on medical imaging. 2015;34:1843-53.

16. Lasič S, Yuldasheva N, Szczepankiewicz F, Nilsson M, Budde M, Dall’Armellina E, Schneider JE, Teh I and Lundell H. Stay on the Beat With Tensor-Valued Encoding [Dataset and Code]; https://archive.researchdata.leeds.ac.uk/950/. 2022.

17. Das A, Chowdhary A, Kelly C, Teh I, Stoeck CT, Kozerke S, Maxwell N, Craven TP, Jex NJ, Saunderson CED, Brown LAE, Ben-Arzi H, Sengupta A, Page SP, Swoboda PP, Greenwood JP, Schneider JE, Plein S and Dall'Armellina E. Insight Into Myocardial Microstructure of Athletes and Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Patients Using Diffusion Tensor Imaging. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging : JMRI. 2021;53:73-82.

18. Farzi M, McClymont D, Whittington H, Zdora MC, Khazin L, Lygate CA, Rau C, Dall'Armellina E, Teh I and Schneider JE. Assessing Myocardial Microstructure with Biophysical Models of Diffusion MRI. IEEE transactions on medical imaging. 2021;PP.

Figures