0314

Fast and High-resolution Luminal Water Imaging in the Prostate Based on Echo Merging and k-t Undersampling with Reduced Refocusing Flip Angles1The Institute of Science and Technology for Brain-inspired Intelligence, Fudan University, Shanghai, China, 2Department of Radiology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom, 3Shanghai Jiao Tong University University, Shanghai, China, 4Department of Radiology, CUH NHS Foundation Trust, Cambridge, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: Prostate, Cancer

The clinical application of luminal water imaging (LWI) has been restricted by its long acquisition time. We present a high acceleration method based on T2 mapping using echo merging plus k-t undersampling with reduced flip angles (TEMPURA), which enables a fast acquisition in 2.8 min as well as a high-resolution acquisition in 5.4 min. Their performance was evaluated on 13 patients with biopsy-proven prostate cancer. Compared with the standard acquisition in 8.3 min, both the fast and high-resolution methods showed a high correlation in LWI measurements and consistent diagnostic performance in detecting malignant lesions.

Introduction

Luminal water imaging (LWI) is an MR technique that has been recently developed for non‐invasive detection and grading of prostate carcinoma, which obtains multiple parameters from a series of consecutive T2 weighted (T2W) images (1). However, LWI is very time-consuming, requiring a large number of echoes and long echo times, which limits its clinical application. Here, we proposed a highly accelerated multi-echo spin-echo sequence based on T2 mapping using Echo Merging Plus k-t Undersampling with Reduced flip Angles (TEMPURA). A fast LWI method (Fast) and a high-resolution LWI method (HR) were developed and evaluated on patients with biopsy-proven prostate cancer. Their performance was compared with a standard LWI acquisition (Std) (2).Methods

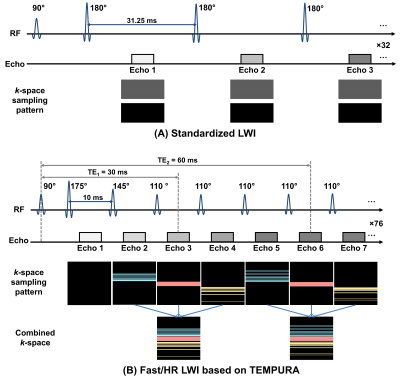

The acquisition schemes of the standard LWI and Fast/HR LWI based on TEMPURA are shown in Figure 1. Every three adjacent echoes are combined into one k-space, which is randomly undersampled (×2.5) and can be reconstructed based on compressed sensing (CS) theory. The total acceleration factor is 7.5. Reduced flip angles (175°-145°-110°…-110°) are used for the refocusing pulses to reduce the specific absorption rate, so that echo spacings can be reduced to a minimum of 10 ms, and thus more echoes can be acquired to benefit CS reconstruction. The first echo is discarded to reduce the effect of stimulated echoes. k-t FOCUSS (3) was used for CS reconstruction. The DECAES algorithm (4) was used as a multi-compartment fitting model with stimulated echo compensation.A standard LWI using constant 180° flip angles, accelerated by SENSE (×2) and half-Fourier sampling, was used as a reference method. The key parameters for LWI sequences are echo spacing(ms)/ΔTE(ms)/number of echoes: 31.25/31.25/32 (Std), 10/30/76 (Fast), 10/30/76 (HR); repetition time (ms): 6091 (Std), 4638 (Fast), 4638 (HR); acquired matrix size: 128×128 (Std), 128×128 (Fast), 256×256 (HR); slice number 12; FOV 240×240 mm2, acquisition time (seconds): 500 (Std), 325 (HR), 168 (Fast). Other sequences in a routine protocol include axial fast spin-echo (FSE) T1WI, axial FSE T2WI and axial DWI (b-values: 100, 750, 1400 s/mm2).

Thirteen patients with biopsy-proven prostate cancer were imaged using a 3 T system (Discovery MR750; GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) and a 32-channel cardiac array coil. The median patient age was 67 years (range, 61-74 years), and the median prostate-specific Thirteen patients with biopsy-proven prostate cancer (median age: 67 years, age range: 61-74 years; median prostate-specific antigen (PSA): 4.8 ng/mL, range: 2.9-7.3 ng/mL) were imaged using a 3 T system (Discovery MR750; GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) and a 32-channel cardiac array coil. Studies were approved by the local research ethics committee, and all participants gave informed consent.

ROIs were drawn manually by two experienced urogenital radiologists, in consensus using open-source segmentation software ITK-SNAP. Tumour ROIs included PI-RADS ≥3 lesions that harboured biopsy-proven PCa, while nontumoural ROIs included regions of normal-appearing prostate that were proven to be benign on biopsy. ROIs were placed on in transition zone (TZ) and peripheral zone (PZ) separately on T2W images and then converted to registered LWI maps.

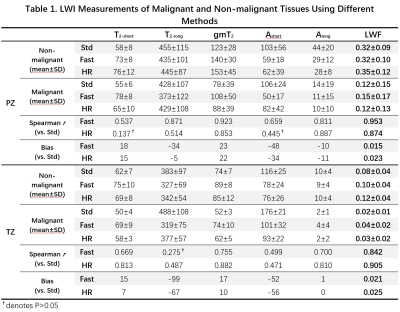

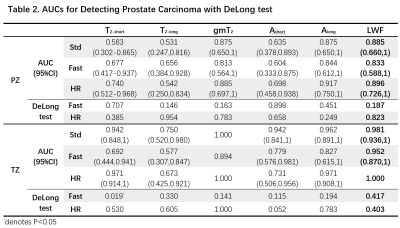

Spearman rank correlation coefficients were calculated to assess the correlation of Fast/HR with Std in LWI measurements, including luminal water fraction (LWF), geometric mean T2 (gmT2), geometric mean of the short (T2-short) and long (T2-long) components, and areas under the short (Ashort) and long (Along) components. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis based on a logistic generalized linear model was performed to assess the diagnostic performance of LWI parameters obtained by different methods for differentiation between benign tissues and malignant lesions. Area under the curve (AUC) was calculated and compared between Fast/HR and Std using a Delong test.

Results

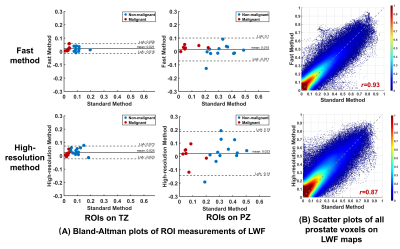

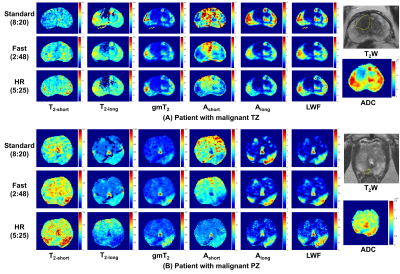

Figure 2 shows representative maps of LWI parameters from two patients with histologically confirmed malignant lesions in TZ and PZ respectively. LWI measurements of malignant and nonmalignant tissues using different methods are summarized in Table 1. Both Fast and HR show significant correlation with Std on most parameters except T2-long in TZ for Fast and T2-short and Ashort in PZ for HR. Fast and HR both show high correlation coefficient (0.953/0.842 and 0.874/0.905) and low bias (0.015/0.021 and 0.023/0.025) in LWF measurements. The consistency in LWF can also be observed in Figure 3 showing Bland-Altman plots of ROI measurements from all patients and scatter plots of all prostate voxels in 5 randomly-selected patients.Table 2 shows ROC analysis with a Delong test. No significant difference exists in diagnostic performance between Fast/HR and Std among all parameters except T2-short measured by Fast in TZ region (P < 0.05).

Discussion and Conclusion

Conventional LWI with 30 or 32 echoes used in most previous literature (2,5–7) requires more than 8 min for the acquisition of 12 slices. We have presented a highly accelerated prostate LWI method based on TEMPURA, which combines echo merging with k-t undersampling and uses reduced refocusing flip angles to acquire more echoes. A fast and a high-resolution LWI sequence were both presented. The results show that the fast method reduced the acquisition time by a factor of 3 (from 500 to 168 s), and the high-resolution method reduced the acquisition time by a factor of 1.5 while increasing the resolution by a factor of 2 in both in-plane directions (from 1.88×1.88 to 0.94×0.94 mm2). Compared with the standard method, both the fast and high-resolution method showed high correlation in all LWI measurements and no significant difference in the diagnostic performance, except for some less important intermediate parameters.Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge support from National Institute of Health Research Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre, Cancer Research UK (Cambridge Imaging Centre grant number C197/A16465), the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council Imaging Centre in Cambridge and Manchester, and the Cambridge Experimental Cancer Medicine Centre.

References

1. Sabouri S, Chang SD, Savdie R, et al. Luminal water imaging: A new MR imaging T2 mapping technique for prostate cancer diagnosis. Radiology 2017;284:451–459 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2017161687.

2. Devine W, Giganti F, Johnston EW, et al. Simplified Luminal Water Imaging for the Detection of Prostate Cancer From Multiecho T2 MR Images. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2019;50:910–917 doi: 10.1002/jmri.26608.

3. Jung H, Sung K, Nayak KS, Kim EY, Ye JC. K-t FOCUSS: A general compressed sensing framework for high resolution dynamic MRI. Magn. Reson. Med. 2009;61:103–116 doi: 10.1002/mrm.21757.

4. Doucette J, Kames C, Rauscher A. DECAES – DEcomposition and Component Analysis of Exponential Signals. Z. Med. Phys. 2020;30:271–278 doi: 10.1016/j.zemedi.2020.04.001.

5. Storås TH, Gjesdal KI, Gadmar ØB, Geitung JT, Kløw NE. Prostate magnetic resonance imaging: Multiexponential T2 decay in prostate tissue. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2008;28:1166–1172 doi: 10.1002/jmri.21534.

6. Carlin D, Orton MR, Collins D, deSouza NM. Probing structure of normal and malignant prostate tissue before and after radiation therapy with luminal water fraction and diffusion-weighted MRI. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2019;50:619–627 doi: 10.1002/jmri.26597.

7. Hectors SJ, Said D, Gnerre J, Tewari A, Taouli B. Luminal Water Imaging: Comparison With Diffusion-Weighted Imaging (DWI) and PI-RADS for Characterization of Prostate Cancer Aggressiveness. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2020;52:271–279 doi: 10.1002/jmri.27050.

Figures

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of the multi-echo spin-echo sequences for LWI. (A) Standard LWI using constant flip angles with SENSE (×2) and half-Fourier sampling. (B) Fast and HR LWI based on TEMPURA.

Figure 2. Representative maps of LWI parameters from two patients with histologically confirmed malignant lesions in TZ (A) and PZ (B). The yellow boundaries in T2W indicate the lesions.