0251

Association between Post-traumatic Osteoarthritis 10+ Years after ACLR and Quantitative MRI of Knee Cartilage, Menisci, and Thigh Muscles1Biomedical Engineering, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH, United States, 2Program of Advanced Musculoskeletal Imaging (PAMI), Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH, United States, 3Department of Diagnostic Radiology, Cleveland Clinic Imaging Institute, Cleveland, OH, United States, 4Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA, United States, 5Department of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, United States, 6Radiology and Radiological Sciences, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, United States, 7Department of Radiology, The Ohio State University Wright Center of Innovation in Biomedical Imaging, Columbus, OH, United States, 8Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, United States, 9Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Radiomics, Relaxometry

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the associations between radiomic features in knee and thigh quantitative MRI with symptomatic and radiographic post-traumatic osteoarthritis (PTOA) after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR). Radiomic features of knee cartilage, menisci (extracted from T1ρ maps), and thigh muscles (extracted from anatomic images and fat fraction maps) were extracted from patient MRI 10+ years after ACLR, and features were selected for symptomatic or radiographic PTOA associations. Symptomatic and radiographic PTOA were associated with features from the medial cartilage compartments, and menisci; features from the thigh muscles were associated with symptomatic PTOA only.

Introduction

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears are a common occurrence among young athletes, and patients with ACL tears have an elevated risk of developing post-traumatic osteoarthritis (PTOA), with or without ACL reconstruction.1 It is important to identify biomarkers related to the onset of PTOA because disease progression is not readily reversed once patients present symptoms.2 Quantitative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) measures, such as T1ρ relaxation time of cartilage and meniscus and intramuscular fat in the thigh, have been related to PTOA,3,4 and could be biomarkers that indicate disease presence. Recent work has used radiomic analysis to discriminate between ACLR patients two years after surgery and healthy controls.5 However, no previous work has applied radiomic analysis, a powerful tool that can identify imaging features from multiple tissues affected by the disease, to identify imaging features associated with symptomatic and radiographic PTOA development after ACLR. The purpose of this study was to evaluate associations between radiomic features from the articular knee cartilage, menisci and thigh muscles and symptomatic and radiograph PTOA at 10+ years after ACLR.Methods

Patient data from an ongoing prospective multisite study adding quantitative MRI to the Onsite nested cohort within the Multicenter Orthopedic Outcomes Network (MOON) cohort were used for this study. Patients underwent ACLR and Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome (KOOS) scores were collected at baseline (post injury and before ACLR) and at 10 years after surgery. At 10 years after ACLR, radiographs and MRI of the knee and mid-thigh were also collected. The radiographs were used to perform Kellgren-Lawrence (KL) grading, and radiographic OA was defined as having a KL grade of two or greater in either knee. Symptomatic OA was defined using 10 year KOOS with the OARSI-OMERACT criteria,6 where KOOS quality-of-life < 87.5 and two or more additional criteria: KOOS-pain < 86.1, KOOS-symptoms < 85.7, KOOS-function in daily-living < 86.8, KOOS-function in sport/recreation < 85.0.Knee MRI included a dual-echo steady state (DESS) sequence (0.36x0.36x0.70 mm3), and a magnetization-prepared angle-modulated partitioned k-space spoiled gradient echo snapshots (MAPSS) T1ρ imaging sequence7 (0.44x0.44x4.00 mm3). Mid-thigh MRI included a T1-weighted turbo spin-echo (TSE) sequence (0.78x0.78x5.00 mm3) and an axial 6-point Dixon scan (1.56x1.56x5.00 mm3). DESS images were registered to MAPSS images, which were used to generate T1ρ maps across the knee. Cartilage and menisci were automatically segmented in registered DESS images into medial/lateral femoral, medial/lateral tibial, trochlear and patellar cartilage, and the medial/lateral menisci using an in-house deep learning model.8 Dixon images were used to generate fat-fraction maps across the mid-thigh, and TSE images were registered to the Dixon images. Thigh muscles, quadriceps, hamstrings and adductor groups,4 were segmented automatically in the registered TSE images using an in-house deep learning model. The T1ρ maps and cartilage and meniscus segmentation (eight ROIs) were used to extract 3D radiomic features including first order intensity, texture, and shape. One axial slice of the muscle segmentations (three ROIs) were used to extract similar 2D radiomic features from thigh fat-fraction maps and TSE images. A total of 10658 radiomic features were extracted per patient. Clinical features including graft-type, age, sex, BMI, Marx activity scores and KOOS at baseline were evaluated alongside radiomic features during feature selection. Initial features were selected using the Boruta method, where the models predicted either symptomatic or radiographic OA, and a maximum-relevance minimum-redundancy algorithm generated a reduced set of 11 features. Five-fold cross-validation was used where training and test data were divided 80:20. Class imbalances were addressed by oversampling the minority to achieve a 50-50 split between positive and negative cases. The cross-validation scheme was repeated 500 times for a total of 2500 permutations. Performance was quantified using the mean and standard deviation of the area under the receiver-operating curves (AUROC), sensitivity, and specificity across the 2500 permutations.

Results

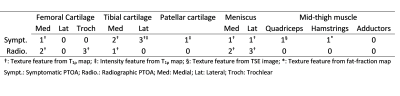

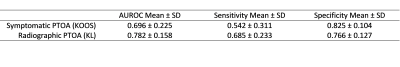

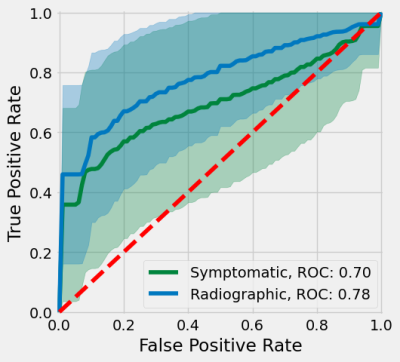

Patient demographics are shown in Table 1. All selected radiomic features for radiographic PTOA were related to texture, and nine selected features for symptomatic PTOA were related to texture and two related to intensity (Table 2). Both symptomatic and radiographic PTOA were associated with features selected from the medial cartilage compartments and menisci (Table 2). Features for quadriceps and hamstring muscles and lateral tibial and patellar cartilage were only associated with symptomatic PTOA. Conversely, features for the trochlear groove were only associated with radiographic PTOA (Table 2). Selected features yielded higher AUROC of radiographic (0.782) compared to symptomatic (0.696) PTOA predictions (Table 3, Figure 1).Discussion

This work demonstrates that radiomic features from knee cartilage, menisci, and mid-thigh muscles can be associated with symptomatic and radiographic PTOA after ACLR. Results indicate that both symptomatic and radiographic PTOA are associated with radiomic features from the medial cartilage compartments, and menisci, while only symptomatic PTOA is associated thigh muscle features. It is notable that none of the evaluated clinical features were selected during the feature selection process. We will include radiomic features from other tissues and joint lesions in the future, such as fat pad, bone marrow edema-like lesion and effusion.Conclusion

The results indicate that symptomatic and radiographic PTOA may be influenced by medial cartilage compartments and menisci, where thigh muscles may be more associated with symptomatic PTOA.Acknowledgements

The work was supported by NIH/NIAMS R01AR075422 and by the Arthritis Foundation.References

1. Lohmander, L. S., Englund, P. M., Dahl, L. L. & Roos, E. M. The Long-term Consequence of Anterior Cruciate Ligament and Meniscus Injuries: Osteoarthritis. Am. J. Sports Med. 35, 1756–1769 (2007).

2. Chu, C. R. et al. Visualizing pre-osteoarthritis: Integrating MRI UTE-T2* with mechanics and biology to combat osteoarthritis—The 2019 Elizabeth Winston Lanier Kappa Delta Award. J. Orthop. Res. 39, 1585–1595 (2021).

3. Li, X. et al. In vivo T1rho and T2 mapping of articular cartilage in osteoarthritis of the knee using 3T MRI. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 15, 789–797 (2007).

4. Kumar, D. et al. Quadriceps intramuscular fat fraction rather than muscle size is associated with knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 22, 226–234 (2014).

5. Xie, Y. et al. Radiomics Feature Analysis of Cartilage and Subchondral Bone in Differentiating Knees Predisposed to Posttraumatic Osteoarthritis after Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction from Healthy Knees. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, e4351499 (2021).

6. Wasserstein, D. et al. KOOS pain as a marker for significant knee pain two and six years after primary ACL reconstruction: a Multicenter Orthopaedic Outcomes Network (MOON) prospective longitudinal cohort study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 23, 1674–1684 (2015).

7. Li, X., Han, E. T., Busse, R. F. & Majumdar, S. In vivo T1ρ mapping in cartilage using 3D magnetization-prepared angle-modulated partitioned k-space spoiled gradient echo snapshots (3D MAPSS). Magn. Reson. Med. 59, 298–307 (2008).

8. Gaj, S., Yang, M., Nakamura, K. & Li, X. Automated cartilage and meniscus segmentation of knee MRI with conditional generative adversarial networks. Magn. Reson. Med. 84, 437–449 (2020).

Figures

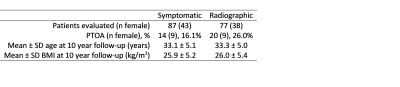

Table 1: The number of patients evaluated for symptomatic and radiographic PTOA and the corresponding demographics.