0235

Dynamic co-fluctuation patterns of fMRI brain activity in temporal lobe epilepsy1Biomedical Engineering, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, United States, 2Radiology and Radiological Sciences, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, United States, 3Electrical and Computer Engineering, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, United States, 4Neurological Surgery, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Brain Connectivity, Epilepsy

Temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) presents with transient epileptic activity at rest, typically originating from the hippocampus. Here we measure dynamic functional connectivity (FC) at single functional MRI timepoints with edge timeseries to detect recurring hippocampal co-fluctuation patterns and their alterations in TLE. Three anterior hippocampus co-fluctuation patterns were detected in healthy controls. One pattern was altered in TLE, while another pattern was more frequent in TLE than controls. These changes reflect alterations in dynamic spatial patterns of FC from the epileptic focus in TLE.

Introduction

Temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) is characterized by seizures originating from the temporal lobe, typically from within the hippocampus. Previous resting-state functional MRI (fMRI) studies have found static functional connectivity (FC) alterations in TLE largely involving the hippocampus1–4. However, TLE patients present with transient interictal epileptic activity at rest5, which has led to studies of FC dynamics in TLE using sliding windows6,7. Esfahlani et al. recently proposed a novel method to obtain dynamic FC from fMRI at single timepoints and found that “co-fluctuation events” at single timepoints largely contribute to static FC8. This single-timepoint dynamic FC, known as “edge timeseries”, presents an opportunity to study alterations in brief patterns of FC in TLE that may be linked to transient epileptic activity. Here we use edge timeseries to detect healthy, recurring hippocampal co-fluctuation patterns and determine whether these patterns are altered in TLE.Methods

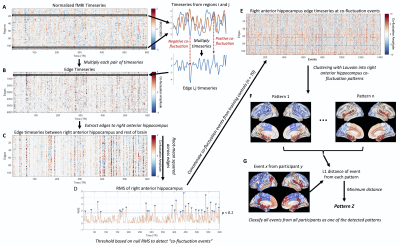

This study included 96 healthy controls (37.9 ± 13.4 yrs, 46 female), randomly split into training (n = 70) and testing (n = 26) groups, along with 23 right TLE (RTLE) patients (42.5 ± 12.6 yrs, 14 female). All participants underwent 3T MRI scanning including a T1-weighted scan (1x1x1 mm3) and two consecutive 10 min resting-state fMRI scans (TR = 2 s, 3x3x4 mm3). The T1-weighted scan was used to segment 107 brain regions with a multi-atlas method9 as well as anterior and posterior hippocampi with Freesurfer 610,11, resulting in 111 regions total.fMRI data underwent standard preprocessing including correction for physiological noise with RETROICOR12 and the two scans were concatenated in time. Normalized timeseries from each pair of regions were multiplied to obtain the edge timeseries8 (Fig 1A-B). The 110 edges to the right anterior hippocampus were extracted (Fig 1C) and the root-mean squared (RMS) amplitude at each timepoint was taken across these edge timeseries to obtain the right anterior hippocampus RMS signal8 (Fig 1D). A null distribution of right anterior hippocampus RMS signals were obtained for each subject by shuffling regional timeseries. Co-fluctuation events were detected as peaks in the RMS signal that exceeded the null distribution at p < 0.113 (Fig 1D). The edge timeseries to the anterior hippocampus at detected co-fluctuation events from the training controls were clustered into patterns using consensus clustering with the Louvain algorithm13,14 (Fig 1F). The centroids of these clusters reflect patterns of co-fluctuation between the right anterior hippocampus and the rest of the brain at each event, with positive and negative values depicting whether regions are in or out of phase with the right anterior hippocampus. Co-fluctuation events from all participants were then classified as the pattern with the minimum L1 distance to the event (Fig 1G).

Individual patterns were computed for each participant as the average of events corresponding to each of the patterns for that participant. The L1 distance from individuals’ patterns to the pattern centroids were then calculated. The occurrence rate of each pattern was calculated as the fraction of events labeled as each pattern for each participant. Distances and occurrence rates of each pattern were compared between groups with Wilcoxon rank-sum tests.

Results

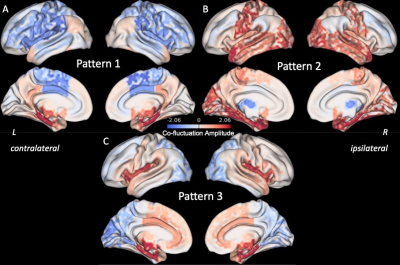

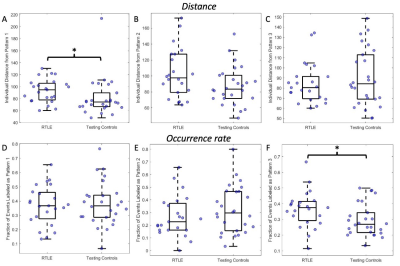

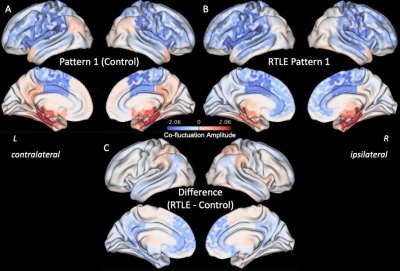

Three right anterior hippocampus co-fluctuation patterns were detected (Fig 2). Pattern 1 includes positive co-fluctuations with medial temporal, subcortical, and default mode network (DMN) regions along with negative co-fluctuations with sensorimotor and lateral frontal regions (Fig 2A). Pattern 2 includes positive co-fluctuations with temporal, occipital, and sensorimotor regions along with negative co-fluctuations with the thalami (Fig 2B). Pattern 3 includes positive co-fluctuations with medial temporal and insular regions along with negative co-fluctuations with occipital regions (Fig 2C).Training and testing controls had no differences in the distances or occurrence rates of any of the three patterns (punc > 0.05). RTLE patients had a higher distance from Pattern 1 than testing controls (punc < 0.05, Fig 3A). This increased distance in Pattern 1 was due to decreased co-fluctuations with the DMN and left/contralateral medial temporal regions along with increased co-fluctuations with the thalami and lateral parietal regions compared to controls (Fig 4). RTLE also had a higher occurrence rate of Pattern 3 compared to testing controls (punc < 0.05, Fig 3F).

Discussion & Conclusion

In this study we detected three recurring co-fluctuation patterns of the right anterior hippocampus. We found that the pattern with positive co-fluctuations to medial temporal and DMN regions was altered in RTLE patients. Additionally, we found that the pattern with positive co-fluctuations to medial temporal and insular regions and negative co-fluctuations to the occipital lobe occurred at a higher rate in RTLE than in controls. Further studies can investigate whether these alterations in dynamic patterns of brain activity in TLE are linked to transient interictal epileptic activity using simultaneous electrophysiology and fMRI.Acknowledgements

This study was supported by NIH T32 EB021937, NIH R01 NS075270, NIH R01 NS108445, NIH R01 NS110130, and NIH R00 NS097618.References

1. Bettus G, Guedj E, Joyeux F, et al. Decreased basal fMRI functional connectivity in epileptogenic networks and contralateral compensatory mechanisms. Hum Brain Mapp. 2009;30(5):1580-1591. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.20625

2. Englot DJ, Konrad PE, Morgan VL. Regional and global connectivity disturbances in focal epilepsy, related neurocognitive sequelae, and potential mechanistic underpinnings. Epilepsia. 2016;57(10):1546-1557. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.13510

3. Pereira FR, Alessio A, Sercheli MS, et al. Asymmetrical hippocampal connectivity in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy: evidence from resting state fMRI. BMC Neurosci. 2010;11(1):66. doi:10.1186/1471-2202-11-66

4. Haneef Z, Lenartowicz A, Yeh HJ, Levin HS, Engel Jr J, Stern JM. Functional connectivity of hippocampal networks in temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2014;55(1):137-145. doi:10.1111/epi.12476

5. Engel J. Mesial Temporal Lobe Epilepsy: What Have We Learned? The Neuroscientist. 2001;7(4):340-352. doi:10.1177/107385840100700410

6. Morgan VL, Chang C, Englot DJ, Rogers BP. Temporal lobe epilepsy alters spatio-temporal dynamics of the hippocampal functional network. NeuroImage Clin. 2020;26:102254. doi:10.1016/j.nicl.2020.102254

7. Li R, Deng C, Wang X, et al. Interictal dynamic network transitions in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2022;63(9):2242-2255. doi:10.1111/epi.17325

8. Esfahlani FZ, Jo Y, Faskowitz J, et al. High-amplitude cofluctuations in cortical activity drive functional connectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2020;117(45):28393-28401. doi:10.1073/pnas.2005531117

9. Huo Y, Plassard AJ, Carass A, et al. Consistent cortical reconstruction and multi-atlas brain segmentation. NeuroImage. 2016;138:197-210. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.05.030

10. Fischl B. FreeSurfer. NeuroImage. 2012;62(2):774-781. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.01.021

11. McHugo M, Talati P, Woodward ND, Armstrong K, Blackford JU, Heckers S. Regionally specific volume deficits along the hippocampal long axis in early and chronic psychosis. NeuroImage Clin. 2018;20:1106-1114. doi:10.1016/j.nicl.2018.10.021

12. Glover GH, Li TQ, Ress D. Image-based method for retrospective correction of physiological motion effects in fMRI: RETROICOR. Magn Reson Med. 2000;44(1):162-167. doi:10.1002/1522-2594(200007)44:1<162::AID-MRM23>3.0.CO;2-E

13. Betzel RF, Cutts SA, Greenwell S, Faskowitz J, Sporns O. Individualized event structure drives individual differences in whole-brain functional connectivity. NeuroImage. 2022;252:118993. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2022.118993

14. Lancichinetti A, Fortunato S. Consensus clustering in complex networks. Sci Rep. 2012;2(1):336. doi:10.1038/srep00336

Figures