0231

Mapping functional connectivity of insular subdivisions using connectivity-based parcellation in adolescents with major depressive disorder1Huaxi MR Research Center (HMRRC), Functional and Molecular Imaging Key Laboratory of Sichuan Province, Department of Radiology, West China Hospital of Sichuan University, Chengdu, China, Chengdu, China, 2Department of Radiology, the Third Hospital of Mianyang, Sichuan Mental Health Center, Mianyang, China, Mianyang, China, 3Department of Psychiatry, the Third Hospital of Mianyang, Sichuan Mental Health Center, Mianyang, China, Mianyang, China, 4Psychoradiology Research Unit of the Chinese Academy of Medical Science , West China Hospital of Sichuan University, Chengdu, Sichuan, China, Chengdu, China

Synopsis

Keywords: Psychiatric Disorders, Adolescents, major depressive disorder

Using a data-driven connectivity-based parcellation technique, we identified anterior and posterior functional subdivisions of insula per hemisphere in adolescent population based on their similar functional connectivity profiles. Then, we investigated the distinct functional connectivity of each insular subregion between depressive adolescents and typical developmental controls. The significant unbalanced connectivity of insular subregions with left superior frontal gyrus (SFG) between two groups was revealed, which associated with interpersonal relation, emotional expressiveness, and cognition impairments in depressive adolescents. Our findings indicate that abnormalities in functional architectures of insular subdivisions may be the potential neuroimaging mechanism underlie the specific manifestations in adolescent depression.Introduction

The insula, as a core region of paralimbic system, is widely connected to the cortical, limbic and other paralimbic structures1, and the aberrant functional connectivity of insula and its subregions has been revealed to associate with the pathophysiology of major depressive disorder (MDD)2. Since the lack of insular functional subdivisions derived from the adolescents, it was difficult for previous neuroimaging studies to accurately uncover the abnormal functional connectivity of fined-grained insular subregions in adolescents with MDD (aMDD). A recent data-driven approach of connectivity-based parcellation (CBP)3, 4 makes it possible to segment the insular cortex of adolescent brain based on functional connectivity properties to provide a better representation of the insular functional subdivisions in adolescents. Our current study used the insular subdivisions derived from CBP approach to precisely delineate the fine-grained insular subregional functional connectivity alterations in aMDD patients.Materials & Methods

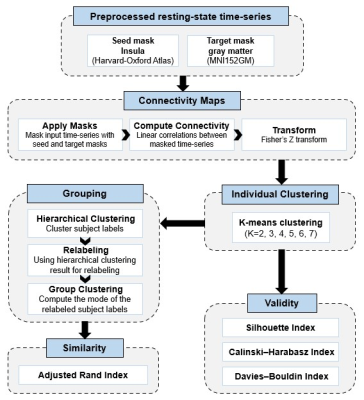

We recruited 65 first-episode drug-naive aMDD patients and 45 age- and gender- matched typically developing controls (TDC) in this study. All participants underwent the 3.0-Telsa Siemens magnetic resonance imaging system equipped with 20-channel phased-array head coil to acquire resting-state functional MRI (rs-fMRI) and high-resolution structural MRI data (T1W image). Neuroimaging data were preprocessed using the fMRIPrep including co-registered rs-fMRI reference to T1W image, slice-timing, motion correction, spatial normalization and smoothing with an isotropic, Gaussian kernel of 6mm full-width half-maximum. The automatic removal of motion artifacts using independent component analysis (ICA-AROMA) was further performed on the preprocessed rs-fMRI data. Finally, the nuisance regression of signals in white matter and cerebrospinal fluid, detrending analysis, and bandpass filtering (0.01–0.08 Hz) was utilized.Connectivity-based parcellation4 was conducted using CBPtools to segment the entire insula per hemisphere into distinct subdivisions based on their resting-state functional connectivity patterns with the rest of whole brain (Figure 1). Briefly, functional connectivity between each insular voxel and every voxel of the rest brain was calculated for each participant. Then, a k-means clustering was applied to the connectivity matrix to assign the insular voxels to a cluster which had the similar connectivity profiles, and obtained the individual insular parcellations. Next, the group-level clustering was calculated, including relabeling the individual clusterings and computing the mode of the relabeled subject-wise clustering. Several cluster quality indicators including the Silhouette Index, the Calinski-Harabasz index, and the Davies-Bouldin index, were obtained to determine the optimal number of clusters. After identifying the insular subregions, the intrinsic functional connectivity maps of each insular subregion were generated for all participants.

The full-factorial analysis of variance was used to test the main effect of diagnosis and the diagnosis-by-subregion interaction, with age, sex and head motion as covariates. The significance threshold was set to Puncorrected < 0.005 at the voxel-level and PFWE-corrected < 0.05 at the cluster-level. Furthermore, we explored the association between clinical variables and rsFC strength from the regions showing significant interaction in aMDD group via Pearson or Spearman correlations according to Kolmogorov-Smirnova normal distribution test.

Results

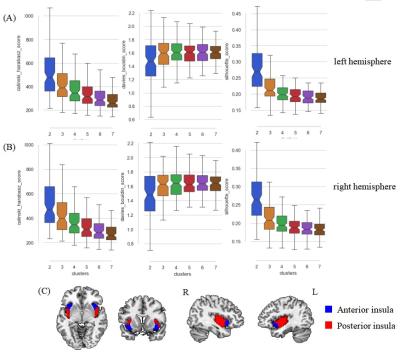

The socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants were provided in Table 1.Two subdivisions of insula (anterior/posterior insula) per hemisphere were identified as the optimal parcellation through the data-driven CBPtool method based on all the cluster quality indicators (Figure 2).

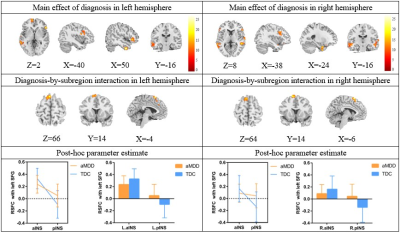

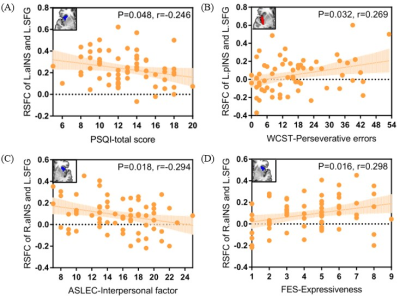

Full-factorial analysis of variance revealed a significant diagnosis-by-subregion interaction in the left superior frontal gyrus (SFG). Specifically, the aMDD patients showed hypoconnectivity of bilateral anterior insula with left SFG and hyperconnectivity of bilateral posterior insula with left SFG (Figure 3), relative to TDC. More interestingly, the connectivity of left anterior insula and left SFG negatively correlated with the total scores of Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), and the connectivity of left posterior insula and left SFG positively correlated with the Perseverative errors of Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST). The lower connectivity of right anterior insula and left SFG correlated with the higher score in Interpersonal factor of Adolescent Self-Rating Life Event Check List (ASLEC) and the lower score in Expressiveness of Family Environment Scale (FES) (Figure 4). In addition, the main effect of diagnosis was also observed, with a general enhancement of connectivity between bilateral insula with orbitofrontal cortex, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, temporal gyrus and hippocampus in aMDD patients compared to TDC.

Discussion & Conclusion

Through the connectivity-based parcellation approach, we found that the two subdivisions of insula are optimal for adolescents. We demonstrated that there were the unbalanced connectivity patterns of insular subdivisions with left SFG in aMDD, which involved in cognitive control and emotion regulation5, 6. Specifically, relative to TDC, the aMDD patients showed the hypoconnectivity of bilateral anterior insula with left SFG (aINS-SFG) and the hyperconnectivity of bilateral posterior insula with left SFG (pINS-SFG). Furthermore, according to our exploratory correlation analysis, the decreased connectivity of aINS-SFG was associate with worse sleep quality, poorer emotional expressiveness and interpersonal relations, while the increased connectivity of pINS-SFG was related to impaired cognition in depressive adolescents. These findings suggest that different alterations in functional architectures of insular subdivisions might underlie the specific cognitive and affective disturbances in adolescent depression.Acknowledgements

This study is supported by grants from the 1.3.5 Project for Disciplines of Excellence, West China Hospital, Sichuan University (Grant No. ZYJC21041), the Clinical and Translational Research Fund of Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (Grant No. 2021-I2M-C&T-B-097), and the Natural Science Foundation of Sichuan Province (Grant No. 2022NSFSC0052).References

1. Ghaziri, J., A. Tucholka, G. Girard, et al., The Corticocortical Structural Connectivity of the Human Insula. Cereb Cortex, 2017. 27(2): p. 1216-1228.

2. Tang, S., L. Lu, L. Zhang, et al., Abnormal amygdala resting-state functional connectivity in adults and adolescents with major depressive disorder: A comparative meta-analysis. EBioMedicine, 2018. 36: p. 436-445.

3. Cao, L., H. Li, J. Liu, et al., Disorganized functional architecture of amygdala subregional networks in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Communications Biology, 2022. 5(1): p. 1184.

4. Reuter, N., S. Genon, S. Kharabian Masouleh, et al., CBPtools: a Python package for regional connectivity-based parcellation. Brain Struct Funct, 2020. 225(4): p. 1261-1275.

5. Frank, D.W., M. Dewitt, M. Hudgens-Haney, et al., Emotion regulation: quantitative meta-analysis of functional activation and deactivation. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 2014. 45: p. 202-11.

6. Niendam, T.A., A.R. Laird, K.L. Ray, et al., Meta-analytic evidence for a superordinate cognitive control network subserving diverse executive functions. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci, 2012. 12(2): p. 241-68.

Figures

Table 1 Demographic

characteristics

* P<

0.05.

aMDD: major

depressive disorder; TDC: typical developing control; SD:

standard deviation; HAMD: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; HAMA:

Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; PSQI: Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index; ASLEC:

Adolescent Self-Rating Life Event Check List; FES: Family Environment Scale; WCST: Wisconsin Card

Sorting Test.

Internal validity scores for all tested solutions (k=2, 3, …, 7) in left (A) and right (B) hemisphere. The higher Silhouette index (left column) and Calinski–Harabasz index (right column) indicate a better fit, whereas a lower Davies–Bouldin index (middle) is better. The two-cluster solution of the insular subdivisions, the anterior and posterior insula of each hemisphere, was identified (C).

Figure

3 The results of the full-factorial analysis of variance per hemisphere

Brain

regions showing significant main effect of diagnosis and significant

diagnosis-by-subregion interaction, as well as the results of post-hoc

parameter estimate for the interaction in left and right hemisphere,

respectively.

aINS: anterior insula; pINS: posterior insula; SFG:

superior frontal gyrus; aMDD: adolescents with major depressive

disorder; TDC: typical developmental controls; L: left; R:

right.

The top left corner of each figure shows the seed region.

RSFC: resting-state functional connectivity; aINS: anterior insula; pINS: posterior insula; SFG: superior frontal gyrus; L: left; R: right; PSQI: Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index; WCST: Wisconsin Card Sorting Test; ASLEC: Adolescent Self-Rating Life Event Check List; FES: Family Environment Scale.