0228

Reorganization of functional networks in squirrel monkey brain after thalamic injury and their relations to task-specific behaviors1Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, United States, 2Vanderbilt University Medical Center, NASHVILLE, TN, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Brain Connectivity, Brain, Thalamus lesion

Resting state fMRI was used to assess whole brain functional networks before and after a targeted, unilateral lesion in the hand and arm representation of the ventroposterior lateral nucleus of the thalamus of squirrel monkeys. Using Independent Component Analysis, the overall whole brain resting state functional connectivity (rsFC) dropped after injury but slowly recovered. The trajectory of network changes corresponded well with quantitative metrics of animal performance on a behavioral task using the affected hand. Some functional networks showed reductions in connectivity post injury followed by recoveries while others reflected compensatory increases that began in the first week after injury.

Introduction

The thalamus is a key relay and integration center for sensory processing in the brain1. An injury to the ventroposterior lateral (VPL) nucleus of the thalamus can result in sensory dysfunction, although plastic changes in subcortical and cortical brain regions are believed to play crucial roles in the functional and behavioral recovery after an injury2,3. Anatomical thalamo-cortical connections have been extensively studied in non-human primates (NHPs)4–8, but not many studies have reported changes in whole brain functional networks after a thalamus injury or how they corresponded with behavioral task performance. In this study, we used Independent Component Analysis (ICA), a data driven method9, to identify the spatial locations of functional hubs within the brain and compute resting state functional connectivity (rsFC) measures between those hubs to quantify the specific effects of a lesion in the thalamic VPL nucleus. We selectively deprived thalamic inputs to cortex by targeted lesions of the hand and arm representation of the VPL and studied their effects on rsFC measures and behavioral recovery in a longitudinal study.Methods

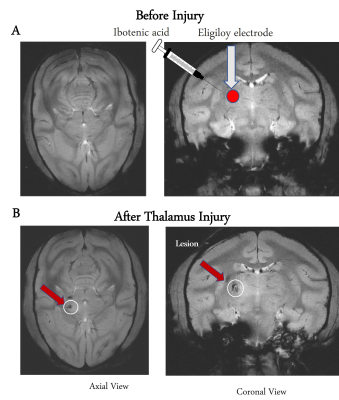

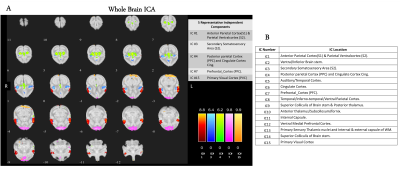

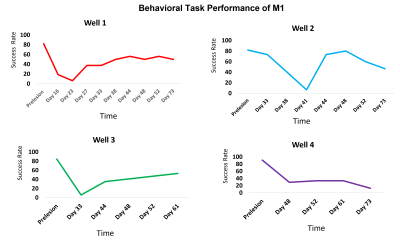

MRI scans were acquired on a Varian/Agilent 9.4T spectrometer covering the whole brain of 19 normal monkeys and 3 thalamus-injured monkeys before and over 8 weeks after injury. High resolution T2*W anatomical images were acquired (24 contiguous slices) along with resting state fMRI echo-planar imaging (EPI) data (TR/TE=1500/16 ms (2 shots), matrix size 64x64, voxel size: 1x1x1 mm3, 300 volumes each run) from the same geometry. Lesions of the hand region representation in VPL were produced in the 3 monkeys by a combination of chemical and electrolytic processes10,11 as shown in the Figure1. The lesion effects are visible by the hypo-intense region on the MRI structural images of post-thalamic lesion monkeys as shown by the arrow in Fig1B. Standard fMRI data preprocessing was performed for whole brain EPI data followed by registration to a squirrel monkey brain atlas (VALiDATe29) using FSL12,13. Next, group spatial ICA was performed on fMRI data from 19 normal monkeys using GIFT software14, and fifteen spatially independent components were extracted from the whole brain. These components were identified to belong to different functional hubs by comparing them with the squirrel monkey brain atlas15. Next, functional connectivities between these hubs were computed from thalamus injured monkeys both before and after injury over multiple weeks, by correlating (Pearson’s correlation) their fMRI time courses, and significant changes were noted.Each thalamus injured monkey was trained before the injury to complete a sugar pellet grasping task and their performances were observed post-injury over 10 weeks. The task involved reaching and retrieving a sugar pellet from four wells in a modified Kluver Board using their dominant hand16. Four wells (numbered Well 1 to Well 4) of different depths and diameters were created to introduce incremental difficulties in the task. Success rates were computed as the ratio between the number of pellets successfully retrieved using the injured dominant hand and the total trials.

Results

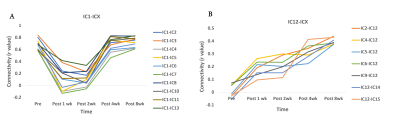

Figure 2A shows five representative functional hubs identified in this study. The locations of all the fifteen hubs are provided in Figure 2B. Figure 3 shows the connectivity changes (combined correlations between all hubs/ROIs), at different stages post-injury. All the monkeys (M1, M2, and M3) underwent a significant dip in connectivity post-injury which recovered with time over 8 to 9-weeks. On a closer look at the individual ICs from a representative monkey M1, we observed that while some correlations follow the overall trend of decrease in connectivity followed by recovery post-injury (Figure 4A), other correlations start to increase monotonically post-injury from Week1 until the last time point (Figure 4B). Figure 5 shows the success rate in the behavioral task from the 4 wells from one representative monkey M1. Decreases in performance occurred for all wells after injury. Success rate at Wells 1, 2, and 3 showed a gradual recovery, which differed based on their difficulty level, while success rate at Well 4 did not show such recovery over the 10-week period observed.Discussion and Conclusion

The location of the majority of the functional hubs obtained using ICA were found to be in regions previously reported in human and macaque brain studies17,18. The overall connectivity changes from the functional hubs showed that connectivity recovers after the initial drop, although the extent of recovery varies across monkeys with some of them recovering back to baseline by the 8th week while others did not. Also, Figure 4 shows connectivity of S1 and S2 region (IC1) with other hubs initially decreased post injury followed by an increase, whereas connectivity of ventral medial pre-frontal cortex (IC12) started to increase from week 1, signifying compensation and neural plasticity post-injury. The behavioral performance of M1 followed the general trend of decreased success after injury followed by recovery, but performance varied across the wells based on their difficulty level. The overall trend corresponded well with the change in functional connectivity measures of M1. Thus, this study demonstrates that functional connectivity changes occur at multiple cortical and sub-cortical regions after a thalamus VPL lesion, and these agree well with specific changes in behavioral performance on a relevant task.Acknowledgements

Funding Source: R01 NS078680.

The authors acknowledge Chaohui Tang for animal preparation and Zou Yue for animal behavioral training.

References

1. Basso MA, Uhlrich D, Bickford ME. Cortical function: A view from the thalamus. Neuron 2005;45:485–8.

2. Tang L, Ge Y, Sodickson DK, et al. Thalamic resting-state functional networks: Disruption in patients with mild traumatic brain injury. Radiology 2011;260:831–40.

3. Pelekanos V, Premereur E, Mitchell DJ, et al. Corticocortical and thalamocortical changes in functional connectivity and white matter structural integrity after reward-guided learning of visuospatial discriminations in Rhesus monkeys. J Neurosci 2020;40:7887–901.

4. K J Huffman LK. Thalamo-cortical connections of areas 3a and M1 in marmoset monkeys. J Comp Neurol 2001:291–310.

5. Baxter MG. Mediodorsal thalamus and cognition in nonhuman primates. Front Syst Neurosci 2013;7:1–5.

6. Goldstone A, Mayhew SD, Hale JR, et al. Thalamic functional connectivity and its association with behavioral performance in older age. Brain Behav 2018;8:1–17.

7. Saalmann YB. Intralaminar and medial thalamic influence on cortical synchrony, information transmission and cognition. Front Syst Neurosci 2014;8:1–8.

8. Davis KD, Kwan CL, Crawley AP, et al. Functional MRI study of thalamic and cortical activations evoked by cutaneous heat, cold, and tactile stimuli. J Neurophysiol 1998;80:1533–46.

9. Independent MRI, Analysis C, Ica S, et al. Resting state fMRI and ICA-Resting state fMRI-Independent Component Analysis (ICA)-Single-subject ICA clean-up-Multi-subject ICA and dual regresson.

10. Koyano KW, Machino A, Takeda M, et al. In vivo visualization of single-unit recording sites using MRI-detectable elgiloy deposit marking. J Neurophysiol 2011;105:1380–92.

11. Murata Y, Higo N, Oishi T, et al. Effects of motor training on the recovery of manual dexterity after primary motor cortex lesion in macaque monkeys. J Neurophysiol 2008;99:773–86.

12. Glover GH, Li TQ, Ress D. Image-based method for retrospective correction of physiological motion effects in fMRI: RETROICOR. Magn Reson Med 2000;44:162–7.

13. Jenkinson M, Smith S. A global optimisation method for robust affine registration of brain images. Med Image Anal 2001;5:143–56.

14. Calhoun VD, Adali T, Pearlson GD, et al. Group ICA of Functional MRI Data: Separability, Stationarity, and Inference. Proc ICA 2001 2001. [Epub ahead of print].

15. Schilling KG, Gao Y, Stepniewska I, et al. The VALiDATe29 MRI Based Multi-Channel Atlas of the Squirrel Monkey Brain. Neuroinformatics 2017;15:321–31.

16. Duque DH, Racca JM, Manzanera Esteve I V, et al. Machine-Learning-Based Video Analysis of Grasping Behavior During Recovery from Cervical Spinal Cord Injury. Behav Brain Res https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2022.114150.

17. Yacoub E, Grier MD, Auerbach EJ, et al. Ultra-high field (10.5 T) resting state fMRI in the macaque. Neuroimage 2020;223.

18. Damoiseaux JS, Rombouts SARB, Barkhof F, et al. Consistent resting-state networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2006;103:13848–53.

Figures

| Figure 5: Behavioral Task performance of monkey M1 over a period of 10 weeks in the 4 wells, measured as success rate/percentage in retrieving sugar pellets from the wells by their injured hand. The wells had increasing levels of difficulty with Well 1 being the least difficult and Well 4 the most difficult. The monkey performed the task on all the days in Well 1. In the more difficult wells it could not perform initially after injury and hence those were excluded from the plot. In all the wells, its performance dropped after injury followed by recovery except Well 4 which was the hardest. . |