0221

Dynamic ASL and Multi-echo BOLD in Hippocampus Functional Connectivity of Aging1State University of New York at Binghamton, Binghamton, NY, United States, 2Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Brain Connectivity, Aging

The effect sizes of aging in hippocampus (HPC) resting-state functional connectivity (rsFC) using dASL and multi-echo BOLD (ME-BOLD) imaging were evaluated in 20 subjects (10 young adults, 10 older adults). Both dASL and ME-BOLD showed reduced HPC rsFC in older adults but with larger extended region in dASL results. dASL demonstrated significantly higher effect sizes of aging in HPC rsFC compared to ME-BOLD, supporting more sensitivity of dASL in detecting the aging effect in HPC rsFC.Introduction

Human brain undergoes structural and functional changes during aging, even in the absence of disease [1]. Disruptions of communication between different functional units are thought to account for the cognitive decline [2]. The hippocampus (HPC) is thought to be one of the key memory regions in the brain [3] and therefore sensitive techniques to measure HPC connectivity with the rest of brain is crucial to our understanding of aging and related cognitive decline. Blood-oxygenation-level dependent (BOLD) imaging has been a popular method to study resting-state functional connectivity (rsFC) [4] of brain and found to provide valuable information in neurological and psychiatric studies [5]. Dynamic arterial spin labeling (dASL) combined with background suppression has recently demonstrated its capability in studying rsFC [6]. dASL [7] and multi-echo BOLD (ME-BOLD) [8, 9] were shown less susceptible to physiological noises, such as cardiac pulsations and respiratory motions. However, HPC rsFC has not been compared between the two techniques directly. Here, we directly compared sensitivity of ME-BOLD based HPC rsFC and dASL based HPC rsFC on detecting the aging effect.Methods

Twenty subjects 10 young adults (age: 28.80 ± 8.69 years) and 10 older adults (age: 69.10 ± 4.89 years), underwent simultaneous resting-state EEG and fMRI (either dASL or ME-BOLD fMRI) acquisitions, but only fMRI data were analyzed in this study. The fMRI imaging data were acquired using a 32-channel receive-only phased-array head coil on a General Electric (GE) 3 Tesla scanner at Cornell University MRI Facility. dASL images were acquired with 3D stack of spirals RARE sequence [6]. Pseudo-continuous arterial spin labeling (PCASL) was used for ASL labeling with 2s labeling duration, 1.8s post-labeling delay, and less than 0.3% of background signals [10]. One hundred and one 3D ASL whole-brain volumes and a reference volume were collected in 9 minutes.ME-BOLD images (3 echos) were acquired with 2D gradient-echo echo planar imaging (EPI). One hundred and eighty TRs (540 BOLD image volumes) were collected in 9 minutes.ME-BOLD volumes were preprocessed following the ME-ICA pipelines to denoise [7] by classifying the ICA components into BOLD components and non-BOLD artifacts and finally combining the BOLD components. The first 4 TRs were removed for stable equilibrium. No preprocessing steps were performed for dASL volumes. The first 5 TRs were removed. Both ME-BOLD and dASL volumes were registered to the standard MNI space using T1-weighted MPRAGE images as intermediate images.

rsFC maps were calculated from the BOLD and dASL image time series with the left HPC and right HPC as seeds. The time series from each seed region was calculated as the mean time series across all the voxels within the seed region (defined by the AAL atlas). The rsFC map for each volunteer and each seed ROI were calculated using Pearson correlation coefficients between time series from the seed ROI and those from the voxels throughout the entire brain and then transformed into z-score maps. For ME-BOLD and dASL separately, rsFC maps were compared between young and old subjects using two-sampled t tests with gender as a covariate on a voxel-by-voxel basis using SPM12. A voxel-level p-value threshold of 0.005 was used. The clusters with cluster-level p value of 0.05 were reported significant. When no significance was observed, we increased the voxel-level p-value threshold in steps of 0.005 to visualize the trend of the aging effect.

The effect size of each method was evaluated on the significant clusters observed from that method. To understand how reliable the effect sizes using dASL and BOLD are, one thousand random permutations were performed on the regional rsFC values by keeping the same number of young and old subjects. The effect size for each method was calculated as the mean of these permutations.

Results & Discussion

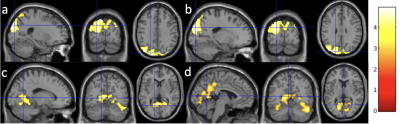

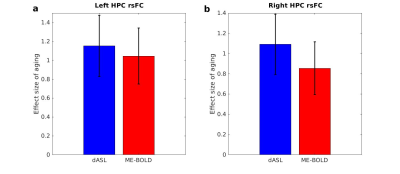

Using the voxel-level p value of 0.005, Older adults exhibited decreased left HPC rsFC with the occipital region (Fig. 1a, cluster size = 5197) and reduced right HPC rsFC with the occipital region (Fig. 1b, cluster size = 4236) using dASL, and reduced left HPC rsFC with the fusiform and lingual region (Fig. 1c, cluster size = 798) using ME-BOLD. Using a more liberal voxel-level p value of 0.01, we observed reduced right HPC rsFC with the fusiform and lingual and precuneus region (Fig. 1d, cluster size = 2007) using BOLD. The age-related changes in HPC rsFC with occipital, fusiform, lingual, and precuneus regions are consistent with literature [11, 12] and memory encoding pathway [13].The effect sizes of aging in left HPC rsFC using dASL and ME-BOLD were 0.9396 and 0.9784, respectively. The effect sizes of aging in right HPC rsFC using dASL and ME-BOLD were 0.8856 and 0.8421, respectively. With random permutations, the effect sizes of aging were significantly higher (p < 0.0001) using dASL (1.15±0.32) than using ME-BOLD (1.04±0.29) in left HPC rsFC (Fig. 2a), and significantly higher (p < 0.0001) using dASL (1.09±0.29) than using ME-BOLD (0.85±0.26) in right HPC rsFC (Fig. 2b).

Conclusion

The study demonstrates dASL is more sensitive to the aging effects in HPC rsFC compared to ME-BOLD. dASL may offer great advantages in reducing the sample size required for future aging and neurodegenerative studies.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Damoiseaux, J.S., Effects of aging on functional and structural brain connectivity. Neuroimage, 2017. 160: p. 32-40.

2. Madden, D.J., et al., Sources of disconnection in neurocognitive aging: cerebral white-matter integrity, resting-state functional connectivity, and white-matter hyperintensity volume. Neurobiol Aging, 2017. 54: p. 199-213.

3. P, A., et al., Historical persepctive: proposed functions, biological characteristics, and neurobiological models of the hippocampus. The hippocampus book. New York: Oxford University Press., 2007.

4. Biswal, B., et al., Functional connectivity in the motor cortex of resting human brain using echo-planar MRI. Magn Reson Med, 1995. 34(4): p. 537-41.

5. Lv, H., et al., Resting-State Functional MRI: Everything That Nonexperts Have Always Wanted to Know. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol, 2018. 39(8): p. 1390-1399.

6. Dai, W., et al., Quantifying fluctuations of resting state networks using arterial spin labeling perfusion MRI. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 2016. 36(3): p. 463-73.

7. Zhao, L., et al., Global Fluctuations of Cerebral Blood Flow Indicate a Global Brain Network Independent of Systemic Factors. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab (In Press), 2017.

8. Kundu, P., et al., Integrated strategy for improving functional connectivity mapping using multiecho fMRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2013. 110(40): p. 16187-92.

9. Poser, B.A., et al., BOLD contrast sensitivity enhancement and artifact reduction with multiecho EPI: parallel-acquired inhomogeneity-desensitized fMRI. Magn Reson Med, 2006. 55(6): p. 1227-35.

10. Maleki, N., W. Dai, and D.C. Alsop, Optimization of background suppression for arterial spin labeling perfusion imaging. Magma, 2012. 25(2): p. 127-33.

11. Tang, L., et al., Differential Functional Connectivity in Anterior and Posterior Hippocampus Supporting the Development of Memory Formation. Front Hum Neurosci, 2020. 14: p. 204.

12. Snytte, J., et al., Volume of the posterior hippocampus mediates age-related differences in spatial context memory and is correlated with increased activity in lateral frontal, parietal and occipital regions in healthy aging. Neuroimage, 2022. 254: p. 119164.

13. Beason-Held, L.L., et al., Hippocampal activation and connectivity in the aging brain. Brain Imaging Behav, 2021. 15(2): p. 711-726.

Figures