0220

Excitation and inhibition in the human M1 during motor memory consolidation and the relation to neural plasticity: a multimodal 7T study1Department of Chemical and Biological Physics, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel, 2Life Sciences Core Facilities, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel

Synopsis

Keywords: Brain Connectivity, Spectroscopy, learning and plasticity

Here, we show, using ultra-high field MRS and functional and structural MRI, how changes in glutamate and GABA in the human motor cortex following motor skill learning may play key roles in promoting motor memory consolidation and neuroplasticity. Increased glutamate after learning was associated with overnight skill performance improvements, and increased functional connectivity of M1 with the striatum, suggesting for functional plasticity. Greater reduction in GABA following learning was associated with increased grey matter volume in M1 overnight, suggesting for structural plasticity. We therefore highlight the importance of these neurochemical modifications in promoting learning and plasticity in the human brain.Background

The learning of new motor skills constitutes an inseparable part of our lives. Following encoding/acquisition, motor memories are continued being processed offline in the brain in a process termed consolidation. During consolidation, motor memories are thought to be strengthened, stabilized, and re-organized in the brain1,2. However, we still lack significant understanding regarding this phase of motor memory processing, and its underlying neural mechanisms. The animal literature has demonstrated that the primary motor cortex (M1) plays a key role in motor memory consolidation, and that learning-induced structural and functional plasticity of M1 support adaptive behaviour3. However, the mechanisms supporting motor memory consolidation and plasticity in the human M1 are not well understood. Neural excitation and inhibition have been proposed to play an important role in the physiological regulation of cognition and behaviour4 and are mediated by glutamate (Glu) and g‑aminobutyric acid (GABA), the main excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters in the brain, respectively. While studies in animals have provided evidence that Glu and GABA may also underpin vital cellular processes mediating M1 plasticity following motor learning5–7, how these neurochemicals may support motor memory consolidation and plasticity in the human M1 remains to be elucidated.Methods

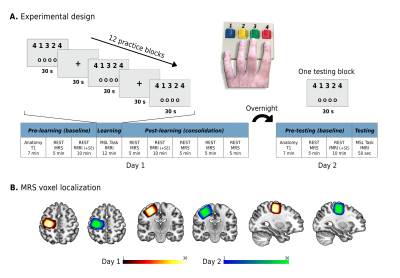

36 young adults (age 27.2±3.8 years, 15 females) participated in the current within-subject repeated measures experiment and were scanned on two consecutive days (Figure 1A). By taking advantage of the increased spatial, temporal, and spectral resolution of ultra-high field 7T (Terra, Siemens) we used 1H-Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (MRS) to non-invasively investigate the dynamics of Glu and GABA in the human M1 prior and during the first 30 minutes after participants learned to perform and practiced a five-digit pressing sequence in the scanner8. We used a single‑voxel SemiLASER sequence (TE = 80ms, TR=7s), previously demonstrated to detect Glu and GABA with good precision9. The MRS voxel was placed in the right M1 (20x20x20 mm3; Figure 1B), as participants learned to perform the sequence with their non-dominant left hand10. Metabolites’ absolute concentrations were calculated using LCModel and were corrected for the voxel’s tissue fractions and relaxation times. Next, we examined how changes in Glu and GABA following learning were associated with overnight changes in skill performance. Furthermore, by implementing a multimodal MR approach combining MRS with functional (a multiband gradient-echo EPI sequence with TR=1s and 1.6mm isotropic voxels) and structural imaging, we also aimed to examine how changes in Glu and GABA following learning were related to: 1) changes in the inter-regional communication (i.e., functional connectivity) of M1 with the putamen, a key region in motor learning11, both following learning and overnight as an expression of learning-induced functional plasticity; and 2) changes in M1 grey matter (GM) volume overnight as an expression of learning-induced structural plasticity. For these analyses an M1 region-of-interest (ROI) was defined as the voxels at the caudal part of the precentral gyrus (which directly controls finger movements)12–14 which demonstrated increased activation on each of the two days. This definition was based on the general definition of memory engram cells15, i.e., cells that are activated by a learning experience, and later reactivated by subsequent memory retrieval. Therefore, this ROI definition enabled us to focus the analysis on voxels containing cell populations that presumably participated in the learning process. The same concept also guided the definition of the putamen ROI.Results

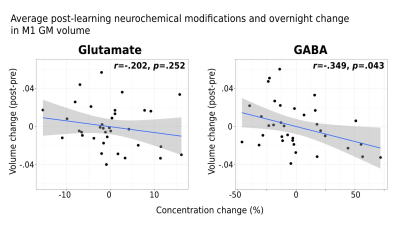

Interestingly, while a linear mixed-effects analysis did not reveal statistically significant changes in either Glu or GABA levels in M1 following learning at the group-level (Figure 2A), significant relationships were observed between the extent of changes in Glu or GABA following learning and changes in the examined neural and behavioural metrics on a subject-by-subject basis. First, we found increased Glu immediately following learning (r=.347, p=.048; Figure 2B) and averaged across the 30 minutes (r=.345, p=.046; Figure 2C) to associate with greater behavioural improvements in motor skill performance overnight. Furthermore, we found increased Glu after learning to correlate with overnight increases in functional connectivity between M1 and the right putamen (r=.368, p=.032) (Figure 3A), and this increased M1-putamen functional connectivity to correlate with the overnight behavioural improvements (r=.291, p=.048) (Figure 3B). Lastly, we found greater reduction in GABA levels following learning to correlate with increased M1 GM volume overnight (r=-.349, p=.043) (Figure 4).Conclusions

Our results provide intriguing microscale mechanistic evidence to the potential distinctive roles Glu and GABA may subserve in supporting motor memory consolidation and the promotion of functional and structural plasticity in the human M1. They also highlight the importance of early neurochemical modifications to memory consolidation and the facilitation of learning and plasticity in the human brain. Furthermore, in addition to the important insights to our basic understanding of the multidimensional mechanisms of learning and plasticity in humans, the current findings may have important clinical implications for rehabilitative settings such as in stroke and brain injury, given the current advances in brain stimulation methods with the potential to manipulate excitation and inhibition in the human brain.Acknowledgements

Assaf Tal acknowledges the support of the Monroy-Marks Career Development Fund the Israeli Science Foundation (personal grant 416/20). Dr. Edna Furman-Haran holds the Calin and Elaine Rovinescu Research Fellow Chair for Brain Research. We would like to acknowledge the receipt of the pulse sequences from the Center for Magnetic Resonance Research (CMRR), University of Minnesota, USA, and to acknowledge Edward J. Auerbach, Ph.D. and Małgorzata Marjańska, Ph.D. (CMRR) for the development of the spectroscopy pulse sequence.References

1. Dudai Y, Karni A, Born J. The Consolidation and Transformation of Memory. Neuron. 2015;88(1):20-32. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.004

2. Dayan E, Cohen LG. Neuroplasticity subserving motor skill learning. Neuron. 2011;72(3):443-454. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2011.10.008

3. Hwang F-J, Roth RH, Wu Y-W, et al. Motor learning selectively strengthens cortical and striatal synapses of motor engram neurons. Neuron. 2022;110(17):2790-2801.e5. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2022.06.006

4. Sohal VS, Rubenstein JLR. Excitation-inhibition balance as a framework for investigating mechanisms in neuropsychiatric disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24(9):1248-1257. doi:10.1038/s41380-019-0426-0

5. Kida H, Mitsushima D. Mechanisms of motor learning mediated by synaptic plasticity in rat primary motor cortex. Neurosci Res. 2018;128:14-18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neures.2017.09.008

6. Trepel C, Racine RJ. GABAergic modulation of neocortical long-term potentiation in the freely moving rat. Synapse. 2000;35(2):120-128. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(200002)35:2<120::AID-SYN4>3.0.CO;2-6

7. Ziemann U, Ilić T V, Pauli C, Meintzschel F, Ruge D. Learning modifies subsequent induction of long-term potentiation-like and long-term depression-like plasticity in human motor cortex. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci. 2004;24(7):1666-1672. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5016-03.2004

8. Herszage J, Sharon H, Censor N. Reactivation-induced motor skill learning. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2021;118(23):e2102242118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2102242118

9. Finkelman T, Furman-Haran E, Paz R, Tal A. Quantifying the excitatory-inhibitory balance: A comparison of SemiLASER and MEGA-SemiLASER for simultaneously measuring GABA and glutamate at 7T. Neuroimage. 2022;247:118810. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2021.118810

10. Yousry TA, Schmid UD, Alkadhi H, et al. Localization of the motor hand area to a knob on the precentral gyrus. A new landmark. Brain. 1997;120 ( Pt 1:141-157. doi:10.1093/brain/120.1.141

11. Doyon J, Benali H. Reorganization and plasticity in the adult brain during learning of motor skills. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2005;15(2):161-167. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2005.03.004

12. Dubbioso R, Madsen KH, Thielscher A, Siebner HR. The Myelin Content of the Human Precentral Hand Knob Reflects Interindividual Differences in Manual Motor Control at the Physiological and Behavioral Level. J Neurosci. 2021;41(14):3163 LP - 3179. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0390-20.2021

13. Witham CL, Fisher KM, Edgley SA, Baker SN. Corticospinal Inputs to Primate Motoneurons Innervating the Forelimb from Two Divisions of Primary Motor Cortex and Area 3a. J Neurosci. 2016;36(9):2605 LP - 2616. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4055-15.2016

14. Rathelot J-A, Strick PL. Subdivisions of primary motor cortex based on cortico-motoneuronal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2009;106(3):918-923. doi:10.1073/pnas.0808362106

15. Josselyn SA, Tonegawa S. Memory engrams: Recalling the past and imagining the future. Science. 2020;367(6473). doi:10.1126/science.aaw4325

Figures