0209

An Improved Intraoral Transverse Loop Coil Design for High Resolution Dental MRI1Division of Medical Physics, Department of Radiology, University Medical Center Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: Non-Array RF Coils, Antennas & Waveguides, New Devices, dental MRI

MRI can simultaneously image soft and hard tissues such as glands, teeth, gum, nerves and bone, thus could be valuable for diagnosis of dental pathologies and implant planning. Intraoral coils have been proved essential to dental MRI due to superior sensitivity compared to external coils. In this study, we introduce a modified transverse loop coil design, which provides improved sensitivity, homogeneity, comfort and safety. We also introduce a bio-compatible, artefact-free and MR-silent coating for intraoral coils. Phantom and in vivo dental MR images demonstrate the advantages of the new intraoral coil design.

Introduction

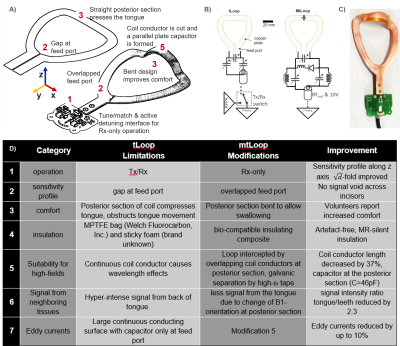

The value of the dental MRI (dMRI) is evident in diagnosis of various pathologies in endodontics [1]–[3], orthodontics [4], craniomaxillofacial surgery [5], and implantology [6]. In dMRI, submillimeter structures must be imaged such as the root canals. To achieve this high resolution in clinically acceptable measurement times, the imaging FOV must be restricted to the target volume. This can be realized by local RF excitation, B1+, or limited receive sensitivity B1- which is tailored to the anatomy, or a combination of both. So far mainly extraoral surface coils and coil arrays have been used [7]–[9]. For an average-sized patient, the distance between an extraoral coil element and a molar tooth is about 30–50 mm, which reduces the sensitivity significantly. Therefore, intraoral coils are preferred [10]–[13].A transmit/receive (Tx/Rx) intraoral loop coil with the coil plane orthogonal to 𝐵0 was proposed [10], where the transverse 𝐵1 fields are sensitive to MR signal. The transverse loop coil (tLoop) can image the whole dental arch including both the upper and the lower teeth. It’s sensitive volume in the occlusal position includes the teeth and supporting structures, and excludes a large portion of the cheeks and the tongue. However, there are several limitations of the tLoop design which we aim to overcome in a modified coil setup (mtLoop) (Fig.1D).

In this work, tLoop and mtLoop designs are compared in terms of sensitivity distributions, image SNR, and eddy currents using electromagnetic (EM) simulations and MRI measurements. Insulation thickness is optimized using EM simulations. Finally, an artefact-free, MR-silent coating was introduced. In vivo dMRI with 250-µm-isotropic resolution was demonstrated for T2-SPACE and UTE sequences.

Methods

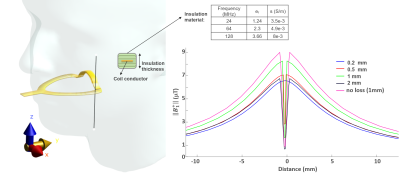

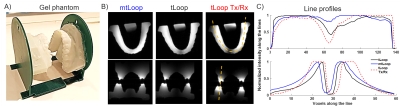

The design of a tLoop and a mtLoop coil are shown in Fig.1. Compared to the tLoop, the mtLoop uses a longer bent coil conductor with a higher inductance (L=50nH and 63nH). Capacitive tuning and matching was applied, and coil conductors were laser-cut from 100µm-thick copper plates. At the mtLoop, a 100µm-thick dielectric tape was used to form a parallel-plate-capacitor at the posterior section.FDTD simulations were performed (Sim4Life v7.0, ZMT, Zurich, Switzerland) to compare the sensitivity along the coil conductor, and the results were compared to measurements. Different thicknesses of the insulating layer (d = 0.2, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0mm) were evaluated. Eddy currents were computed to compare tLoop and mtLoop using a FEM solver (Comsol, The COMSOL AB, Stockholm). MRI measurements were performed at 3T (Prisma-Fit, Siemens). To study the different sensitivity profiles, both tLoop and mtLoop were tested in Rx-only mode. The tLoop was also assessed in Tx/Rx mode [10]. A phantom was 3D-printed from an optical intraoral scan using the insulation material of the intraoral coils; thus, the coils could be tested without additional insulation.

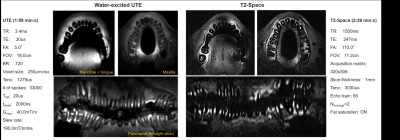

As ultrashort-TE sequences are used in dMRI due to the ultra-short T2* of dentin [12]–[16], the MR-silence as well as image artefacts were tested of the potential insulation materials such as dental resin, bonding fluids, gutta-percha, 3D-printing materials, impression putties and dental cement using a modified ZTE/PETRA sequence [17], [18] (TE=20ms). After coating, coil safety was evaluated [19], and in vivo images were acquired of the whole dental arch at 0.25-mm-isotropic resolution.

Results

In Fig. 2 simulation results show the mtLoop improvement for overlapped feed-port and forming a parallel-plate capacitor at the posterior section. A 3.7-fold sensitivity increase along the incisors, and a 76% signal reduction at the back of the tongue is seen. An insulation-thickness of 1mm was optimal for the given coating material properties at 128MHz (Fig.3).A UV-cured 3D-printing resin mixed with resin powder was MR-silent and did not show image artefacts, and was therefore used to coat the intraoral coils (Fig. 1C). Dental cement was also usable, but had a high conductivity of 0.014S/m (measured with DAKS12, ZMT).

Transverse and coronal phantom images showed a higher SNR in at the incisors (SNR=6721) for the Rx-mtLoop compared to the Rx-tLoop (602) and Tx/Rx-tLoop (72) (Fig. 4), and the SNR ratio of the incisors over the 3rd molars are 1.04, 0.48, and 1.04, respectively. On the contrary, SNR ratio between the tongue and 3rd molars are 0.56, 0.60, 0.84 for mtLoop and Rx-only and Tx/Rx tLoops, respectively.

Maximum temperature rise of 0.4°C at the hot spots was measured with a high-SAR protocol. In Fig. 5, in vivo panoramic images were reconstructed from T2-SPACE (300µm–in-plane-resolution, 1mm-slice thickness), and UTE (250µm-isotropic) sequences. In the transverse slices of mandible, a missing tooth and a metallic filling is observed. The artefact around the metallic filling is larger for T2-SPACE than UTE. In T2-space images, root canals are better visualized than UTE.

Discussion

With mtLoop, we introduced an intraoral transverse loop coil design which has an improved performance over the previously proposed tLoop. As intraoral coils are indispensable components of dMRI, the modifications might help to overcome sensitivity problems, anatomical constraints, patient comfort limitations and loading factor issues.Acknowledgements

The first author gratefully acknowledges the fruitful discussions on the mechanical and material properties of intraoral coils with Djaudat Idiyatullin and Michael Garwood of Center for Magnetic Resonance Research and Beth Groenke, Laurence Gaalaas and Donald Nixdorf of School of Dentistry at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN. We also thank Frank Pfefferkorn of Dentsply DeTrey GmbH, Konstanz, Germany for sending dental material samples.References

[1] Y. Ariji, E. Ariji, M. Nakashima, and K. Iohara, “Magnetic resonance imaging in endodontics: a literature review,” Oral Radiol., vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 10–16, Jan. 2018, doi: 10.1007/s11282-017-0301-0.

[2] W. Leontiev et al., “Suitability of Magnetic Resonance Imaging for Guided Endodontics: Proof of Principle,” J. Endod., vol. 47, no. 6, pp. 954–960, Jun. 2021, doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2021.03.011.

[3] A. Juerchott et al., “Differentiation of periapical granulomas and cysts by using dental MRI: a pilot study,” Int. J. Oral Sci., vol. 10, no. 2, p. 17, Jun. 2018, doi: 10.1038/s41368-018-0017-y.

[4] A. Juerchott et al., “In vivo comparison of MRI- and CBCT-based 3D cephalometric analysis: beginning of a non-ionizing diagnostic era in craniomaxillofacial imaging?,” Eur. Radiol., vol. 30, no. 3, pp. 1488–1497, Mar. 2020, doi: 10.1007/s00330-019-06540-x.

[5] A. Juerchott et al., “In vivo reliability of 3D cephalometric landmark determination on magnetic resonance imaging: a feasibility study,” Clin. Oral Investig., vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 1339–1349, Mar. 2020, doi: 10.1007/s00784-019-03015-7.

[6] T. Hilgenfeld et al., “Use of dental MRI for radiation-free guided dental implant planning: a prospective, in vivo study of accuracy and reliability,” Eur. Radiol., vol. 30, no. 12, pp. 6392–6401, Dec. 2020, doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-07262-1.

[7] J. Sedlacik et al., “Optimized 14 + 1 receive coil array and position system for 3D high-resolution MRI of dental and maxillomandibular structures,” Dentomaxillofacial Radiol., vol. 45, no. 1, p. 20150177, Jan. 2016, doi: 10.1259/dmfr.20150177.

[8] M. Prager, S. Heiland, D. Gareis, T. Hilgenfeld, M. Bendszus, and C. Gaudino, “Dental MRI using a dedicated RF-coil at 3 Tesla,” J. Cranio-Maxillofacial Surg., vol. 43, no. 10, pp. 2175–2182, Dec. 2015, doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2015.10.011.

[9] A.-K. Bracher et al., “Ultrashort echo time (UTE) MRI for the assessment of caries lesions,” Dentomaxillofacial Radiol., vol. 42, no. 6, p. 20120321, Jun. 2013, doi: 10.1259/dmfr.20120321.

[10] D. Idiyatullin, C. a Corum, D. R. Nixdorf, and M. Garwood, “Intraoral approach for imaging teeth using the transverse B 1 field components of an occlusally oriented loop coil,” Magn. Reson. Med., vol. 72, no. 1, pp. 160–165, Jul. 2014, doi: 10.1002/mrm.24893.

[11] U. Ludwig et al., “Dental MRI using wireless intraoral coils.,” Sci. Rep., vol. 6, no. 1, p. 23301, Mar. 2016, doi: 10.1038/srep23301.

[12] A. C. Ozen et al., “Design of an Intraoral Dipole Antenna for Dental Applications,” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng., vol. 68, no. 8, pp. 2563–2573, Aug. 2021, doi: 10.1109/TBME.2021.3055777.

[13] A. S. Tesfai et al., “Inductively Coupled Intraoral Flexible Coil for Increased Visibility of Dental Root Canals in Magnetic Resonance Imaging,” Invest. Radiol., vol. 57, no. 3, pp. 163–170, Mar. 2022, doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000826.

[14] D. Idiyatullin, C. Corum, S. Moeller, H. S. Prasad, M. Garwood, and D. R. Nixdorf, “Dental Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Making the Invisible Visible,” J. Endod., vol. 37, no. 6, pp. 745–752, Jun. 2011, doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2011.02.022.

[15] M. Weiger et al., “High-resolution ZTE imaging of human teeth,” NMR Biomed., vol. 25, no. 10, pp. 1144–1151, 2012, doi: 10.1002/nbm.2783.

[16] D. Idiyatullin, M. Garwood, L. Gaalaas, and D. R. Nixdorf, “Role of MRI for detecting micro cracks in teeth,” Dentomaxillofacial Radiol., vol. 45, no. 7, 2016, doi: 10.1259/dmfr.20160150.

[17] S. Ilbey, P. M. Jungmann, J. Fischer, M. Jung, M. Bock, and A. C. Özen, “Single point imaging with radial acquisition and compressed sensing,” Magn. Reson. Med., vol. 87, no. 6, pp. 2685–2696, Jun. 2022, doi: 10.1002/mrm.29156.

[18] S. Ilbey, M. Jung, U. Emir, M. Bock, and A. C. Özen, “Characterizing Off-center MRI with ZTE,” Z. Med. Phys., vol. 0, pp. 1–8, 2022, doi: ZMEDPHYS-D-22-00099R2.

[19] A. S. Tesfai, S. Reiss, T. Lottner, A. Vollmer, M. Bock, and A. C. Özen, “MR Safety of Inductively-coupled and Conventional Intra-oral Coils,” in Proc. Intl. Soc. Mag. Reson. Med. 30, 2022, p. 5234.

Figures