0198

Intravoxel incoherent motion improves diffusion-weighted imaging in the detection of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer1Institute of Medical Sciences, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen, United Kingdom, 2Department of Oncology, Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, Aberdeen, United Kingdom, 3Department of Radiology, Royal Marsden Hospital, London, United Kingdom, 4Department of Pathology, Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, Aberdeen, United Kingdom, 5Breast Unit, Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, Aberdeen, United Kingdom, 6Translational and Clinical Research Institute, Newcastle University, Aberdeen, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: Breast, MR-Guided Interventions

Breast cancer is a major and expanding health challenge, and neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) is increasingly prescribed to facilitate breast surgery. However, response to NACT is highly inconsistent, imposing an ongoing demand for improved imaging methods for early response identification. Tissue perfusion, a sensitive marker of cancer metabolism, can be derived from intravoxel incoherent motion (IVIM) model, and recent Bayesian algorithm yields increased sensitivity and precision in pancreatic cancer. We therefore hypothesise that IVIM model powered by Bayesian algorithm is able to detect early treatment-induced changes in tumour perfusion and diffusion, with the potential to impact patient care pathway.Introduction

Breast cancer, the most common cancer in women, contributes to 25% of female cancer1. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) is established and increasingly prescribed to facilitate breast surgery2 and improve survival3. Patients without a pathologic complete response (pCR) were reported to have a lower disease-free survival than patients with pCR4, and may suffer from unnecessary cytotoxic chemotherapy and delay in surgery5. Non-invasive imaging markers, sensitive to underlying tumour metabolism for the early identification and prediction of patients without pCR, is crucial for response-guided NACT6. Intravoxel incoherent motion (IVIM) model, coupled with Bayesian probability (BP) algorithm, has demonstrated a higher precision and accuracy in the estimation of microcirculation (f), tissue diffusion (D) and pseudodiffusion (D*) in pancreatic cancer7, 8. We therefore hypothesise Bayesian IVIM model has significant prognostic value in breast cancer patients undergoing NACT.Methods

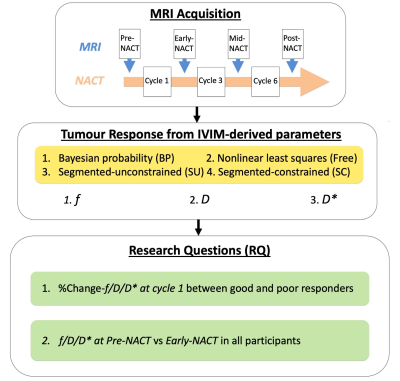

Seventeen patients (age 46 – 58 years) with invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast participated in the clinical trial, with MRI performed at baseline (PRE) and after first cycle (EARLY) (Figure 1). Only patients undergoing NACT, with a tumour size larger than 2 cm on ultrasound were eligible. Women on hormone replacement therapy, having previous breast malignancy and family history of breast cancer were not eligible. Miller-Payne system was used to assess pathologic complete response for good responder9. The study was approved by the London Research Ethics Committee (Identifier: 17/LO/1777), and written informed consent was obtained from all the participants prior to the study.Image Acquisition

All data were acquired on a 3 T whole body clinical MRI scanner (Achieva TX, Philips Healthcare, Best, Netherlands). IVIM images were acquired using pulsed gradient spin echo sequence at 10 b-values (0, 30, 60, 90, 120, 250, 400, 600, 800, 1000 s/mm2)10, with field of view 240 mm × 200 mm × 90 mm, voxel size 2.5 mm × 2.5 mm, slice thickness 5 mm, repetition time 2400 ms and echo time 50 ms.

Image Analysis

The region-of-interests (ROIs) were manually drawn on IVIM image (b = 1000 s/mm2) using ImageJ (v1.58k, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA), inside the tumour edge and avoiding necrotic, haemorrhagic and cystic areas. Data analysis was performed in MATLAB (R2020a, Mathworks, Natrick, MA, USA). Bayesian algorithm estimated the joint posterior distribution, with Monte Carlo simulation to derive a marginalised parameter distribution and input from uniform prior distribution11. Three other analysis approaches, including nonlinear least squares (Free, simultaneous fitting of f, D, and D*), segmented-unconstrained (SU, stepped fitting with D* fitted at second step) and segmented-constrained (SC, stepped fitting with f and D* fitted at second step)12 were also conducted for comparison. Percentage change in IVIM-derived parameters was calculated as: [EARLY – PRE] / PRE × 100(%).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed in the R software (v3.6.3, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The differences in percentage change of f, D, and D* between good and poor responders were compared using Wilcoxon rank sum test. The differences in f, D, and D* between PRE and EARLY were compared using Wilcoxon signed rank paired test.

Results

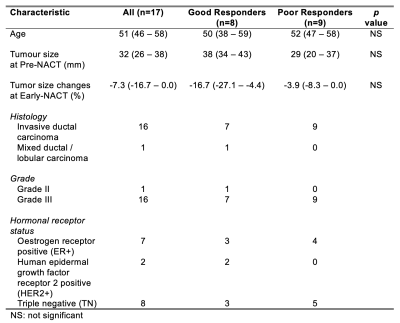

The patient demographic is shown in Table 1.Early Identification (Good Responder vs Poor Responder)

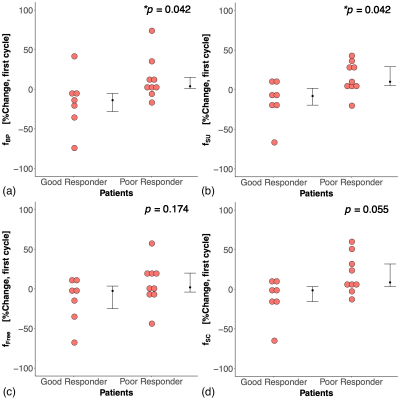

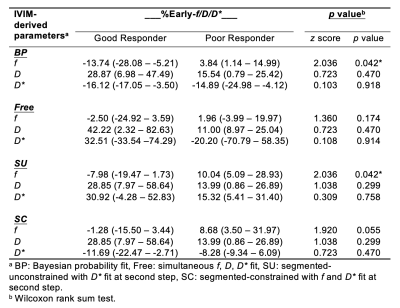

For Bayesian analysis, there was a significant difference (p = 0.042) in percentage change of perfusion fraction between good and poor responders at EARLY, with a decrease in good responders (-13.74 (-28.08 – -5.21)%, n=8) against an increase in poor responders (3.84 (1.14 – 14.99)%, n=9) (Figure 2a, Table 2). For SU analysis, there was also a significant difference (p = 0.042) in percentage change of perfusion fraction between good (-7.98 (-19.47 – 1.73)%) and poor responders (10.04 (5.09 – 28.93)%) (Figure 2b, Table 2). For Free and SC analyses, there were no significant differences between good and poor responders (Figures 2c and 2d, Table 2).

There were no significant differences in percentage change in tissue diffusion and pseudodiffusion between responder groups (Table 2).

Systemic Dynamics (EARLY vs PRE)

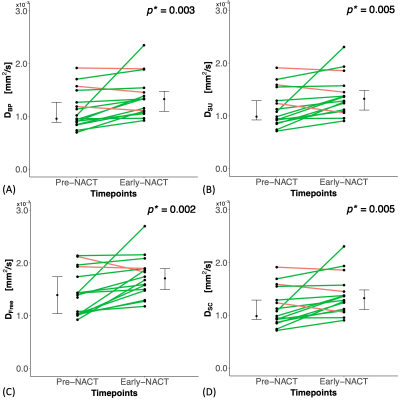

Tissue diffusion was significantly higher (p = 0.003) at EARLY (1.33 (1.10 – 1.48) [×10-3 mm2/s]) against PRE (0.99 (0.89 – 1.32)) for Bayesian analysis, and for SU (p = 0.005, 1.32 (1.11 – 1.48) vs 0.99 (0.92 – 1.29)), Free (p = 0.002, 1.71 (1.49 – 1.89) vs 1.39 (1.04 – 1.74)) and SC (p = 0.005, 1.32 (1.11 – 1.48) vs 0.99 (0.92 – 1.29)) analyses (Figure 3). There were no significant differences in perfusion fraction and pseudodiffusion between EARLY and PRE.

Discussion

An increase in D at EARLY was the most prominent change among the three parameters. The reduction in tissue cellularity leads to an increase in water mobility in the residual tumour and the result suggested the treatment-induced change was systematically dominated by the cellular rather than the vascular component in breast tumours within an individual patient. However, percentage change in f might be useful in differentiation of responder groups at EARLY, and Bayesian IVIM model yielded an effective assessment of f in the evaluation of the magnitude of microcirculation subsequent to the anti-angiogenic effect of NACT.Conclusion

Bayesian perfusion fraction f might be a sensitive biomarker of NACT to improve treatment plan, avoid side effects and expedite alternative treatments in breast cancer.Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Matthew Clemence, Philips Healthcare Clinical Science, UK, for clinical scientist support, Ms Erica Banks and Ms Alison McKay for patient recruitment support, Ms Teresa Morris and Ms Dawn Younie for logistics support, Ms Beverly McLennan, Ms Nichola Crouch, Ms Laura Reid, Mr Mike Hendry for radiographer support, and Dr. Gordon Urquhart for providing access to the patients. This project was jointly funded by Friends of Aberdeen and North Centre for Haematology, Oncology and Radiotherapy (ANCHOR), NHS Grampian Endowment Research Fund and Tenovus Scotland.References

1. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394-424.

2. Santa-Maria CA, Camp M, Cimino-Mathews A, Harvey S, Wright J, Stearns V. Neoadjuvant Therapy for Early-Stage Breast Cancer: Current Practice, Controversies, and Future Directions. Oncology (Williston Park). 2015;29(11):828-38.

3. Kim MM, Allen P, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, et al. Pathologic complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy with trastuzumab predicts for improved survival in women with HER2-overexpressing breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(8):1999-2004.

4. von Minckwitz G, Untch M, Blohmer JU, et al. Definition and impact of pathologic complete response on prognosis after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in various intrinsic breast cancer subtypes. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(15):1796-804.

5. Bagegni NA, Tao Y, Ademuyiwa FO. Clinical outcomes with neoadjuvant versus adjuvant chemotherapy for triple negative breast cancer: A report from the National Cancer Database. PLoS One. 2019;14(9):e0222358.

6. von Minckwitz G, Blohmer JU, Costa SD, et al. Response-Guided Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy for Breast Cancer. JCO. 2013;31(29):3623-30.

7. Barbieri S, Donati OF, Froehlich JM, Thoeny HC. Impact of the calculation algorithm on biexponential fitting of diffusion-weighted MRI in upper abdominal organs. Magn Reson Med. 2016;75(5):2175-84.

8. Gurney-Champion OJ, Klaassen R, Froeling M, et al. Comparison of six fit algorithms for the intra-voxel incoherent motion model of diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging data of pancreatic cancer patients. PLoS One. 2018;13(4):e0194590.

9. Ogston KN, Miller ID, Payne S, et al. A new histological grading system to assess response of breast cancers to primary chemotherapy: prognostic significance and survival. Breast. 2003;12(5):320-7.

10. Bedair R, Priest AN, Patterson AJ, et al. Assessment of early treatment response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer using non-mono-exponential diffusion models: a feasibility study comparing the baseline and mid-treatment MRI examinations. Eur Radiol. 2017;27(7):2726-36.

11. Jalnefjord O, Andersson M, Montelius M, et al. Comparison of methods for estimation of the intravoxel incoherent motion (IVIM) diffusion coefficient (D) and perfusion fraction (f). MAGMA. 2018;31(6):715-23.

12. Kim Y, Kim SH, Lee HW, et al. Intravoxel incoherent motion diffusion-weighted MRI for predicting response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. Magn Reson Imaging. 2018;48(5):27-33.

Figures

Figure 1. Study design

Intravoxel incoherent motion (IVIM) images were acquired at Pre-neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) and Early-NACT. Bayesian probability (BP), Nonlinear least squares (Free), Segmented-unconstrained (SU) and Segmented-constrained (SC) models were used to compute perfusion fraction (f), tissue diffusion (D) and pseudodiffusion (D*) for the assessment of tumour response to NACT. The percentage change in median f, D and D* were compared between good and poor responders (RQ1) with median f, D and D* compared between Pre- and Early-NACT (RQ2).

Figure 2. Percentage changes in perfusion fraction (f) between good and poor responders

The percentage change in f between good and poor responders at Early-NACT from (a) Bayesian probability (BP), (b) Segmented-unconstrained (SU), (c) Nonlinear least squares (Free) and (d) Segmented-constrained (SC) models. There was a significant decrease in f in good responders for BP and SU. Each dot represents the parameter of an individual patient. Error bar represents median (IQR). Statistically significant p values (< 0.05) are marked with an asterisk.

Figure 3. Longitudinal change in tissue diffusion (D) from Pre-NACT to Early-NACT

The change in D at Early-NACT from (a) Bayesian probability (BP), (b) Segmented-unconstrained (SU), (c) Nonlinear least squares (Free) and (d) Segmented-constrained (SC) models. Each dot represents the parameter of an individual patient. Error bar represents median (IQR). Red line shows a net decrease while green line shows a net increase. Statistically significant p values (< 0.05) are marked with an asterisk.

Table 1. Tumour characteristics of patients

Tumour histology and hormonal receptor status grouped by Miller-Payne system (Poor Responders: 1,2,3; Good Responders: 4,5). The median and interquartile range (median (IQR)) of age and tumour size are shown. Statistical significant differences (p < 0.05) are marked with an asterisk.

Table 2. Comparison of IVIM-derived parameters between two responder groups after first cycle of NACT

The percentage change in perfusion fraction (f), tissue diffusion (D) and pseudodiffusion (D*) in good responders (n=8) and poor responders (n=9) from four analysis algorithms. The percentage change at Early-NACT (%Early-f/D/D*) = [Early-f/D/D* – Pre-f/D/D*] / Pre-f/D/D* × 100%. Values are presented as median and interquartile range (median (IQR)). Statistical significant differences (p < 0.05) are marked with an asterisk.