0188

In vivo CEST-Dixon MRI in axillary lymph nodes with and without carcinoma: potential for noninvasive determination of lymph node metastasis

Rachelle Crescenzi1,2, Paula M.C. Donahue3,4, R. Sky Jones5, Chelsea Lee6, Maria Garza1,5, Niral J Patel6, Ingrid Meszoely7, and Manus J Donahue5,8

1Radiology and Radiological Sciences, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, United States, 2Biomedical Engineering, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, United States, 3Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, United States, 4Dayani Center for Health and Wellness, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, United States, 5Department of Neurology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, United States, 6Division of Pediatric Neurology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, United States, 7Department of Surgical Oncology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, United States, 8Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, United States

1Radiology and Radiological Sciences, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, United States, 2Biomedical Engineering, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, United States, 3Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, United States, 4Dayani Center for Health and Wellness, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, United States, 5Department of Neurology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, United States, 6Division of Pediatric Neurology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, United States, 7Department of Surgical Oncology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, United States, 8Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Breast, CEST & MT, cancer, lymph node, metastasis, breast cancer

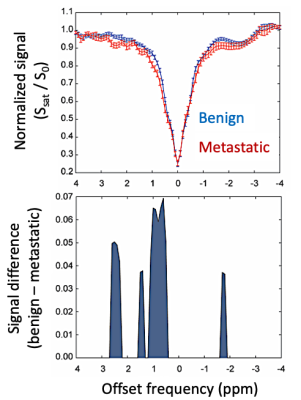

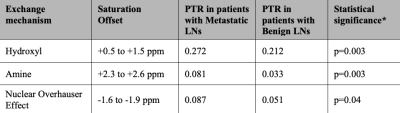

The overall goal of this work is to apply a CEST-Dixon MRI approach in the axillary lymph nodes (LNs) of women with breast cancer to test fundamental hypotheses about biochemical LN profiles with carcinoma. Mean z-spectra and corresponding significant differences in cohorts with metastatic vs. benign LNs were observed in regions of known chemical exchange for the nuclear Overhauser effect (PTR=0.087 vs. 0.051, p=0.04), hydroxyl (PTR=0.272 vs. 0.212, p=0.003), and amine (PTR=0.081 vs. 0.033, p=0.003) protons. CEST-Dixon MRI of LNs may have relevance for pre-surgical breast cancer staging and for guiding LN sparing resections to reduce risk for lymphedema.Introduction

Axillary lymph nodes (LNs) are central to lymphatic immune function and represent the primary reservoir and route for metastatic breast cancer. LN carcinoma cannot be discerned definitively from current diagnostic imaging strategies, and as such, LN removal during lumpectomy or mastectomy can be speculative, require added procedural time for accurate histological staging, and resections are often exaggerated thereby predisposing patients to immune complications and secondary lymphedema (1). Endogenous CEST MRI provides enhanced proton signal contrast through exchange of protons between bulk water and metabolites, and has sensitivity for cancer physiology at the tissue level (2-6). Specific applications to breast cancer and the comorbidity lymphedema, CEST MRI reveals distinct z-spectra in breast tumors, and is also sensitive to protein-rich lymph accumulation in upper-extremities with breast cancer treatment-related lymphedema (7-9); however, application of CEST to LN carcinoma is largely unexplored. Axillary nodal status is a critical element in predicting breast cancer survivorship, as well as identifying extra-axillary and intermammary LN metastasis, and imaging biomarkers would be highlight clinically significant (10, 11). In this study, we evaluated whether pre-operative 3T CEST MRI profiles in axillary LNs are distinct among patients with biopsy-confirmed benign versus metastatic LNs.Methods

Female participants with breast cancer scheduled for clinically-indicated mastectomy or lumpectomy with axillary LN biopsy or dissection were prospectively enrolled from the surgical oncology services and provided written, informed consent.Imaging exam

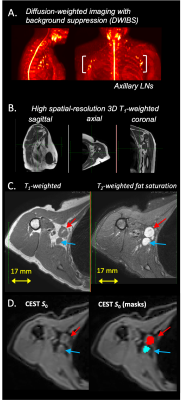

MRI at 3T was performed before LN removal, and the presence of LN carcinoma was determined by the clinical pathology services. Axillary LNs were localized on diffusion-weighted-imaging-with-background-suppression (DWIBS) and 3D T1-weighted MRI (Figure 1A-B). CEST-Dixon MRI was performed using parameters similar to those optimized in musculoskeletal tissue (4). Briefly, a 3D turbo-gradient-echo readout (factor=25; TE1=1.32 ms; DTE=1.1 ms; duration=6min30s) was performed using a train of sinc-gauss pulses (each pulse duration=100 ms; pulses/TR=4; B1=1.5 uT) at a spatial resolution of 2.5x2.5x6 mm (slices=10), with a saturation frequency offset range of -5.5 to +5.5 ppm (stepsize=0.2 ppm) with six equilibrium (S0) acquisitions. A B1 map was separately obtained to ensure >85% of the prescribed B1 over the axillary region (2). Voxel-wise CEST z-spectra were corrected for B0 inhomogeneity of the water resonance, normalized by S0, and the z-spectra from the fat-suppressed Dixon reconstructions preserved.

Image and statistical analyses

LNs were identified and manually segmented on CEST S0 images while referencing T1-weighted and T2-weighted image contrasts to differentiate lymphoid from vascular and other axillary tissues (Figure 1C-D). LNs masks were applied to CEST-weighted images to determine the mean z-spectrum in each LN, and the proton transfer ratio (PTR) was calculated for each saturation frequency offset. LNs were stratified from participants with or without biopsy-confirmed LN carcinoma, and differences in axillary LN CEST PTR between participant groups were evaluated using a Student’s t-test (significance criteria: two-sided p<0.05).

Results

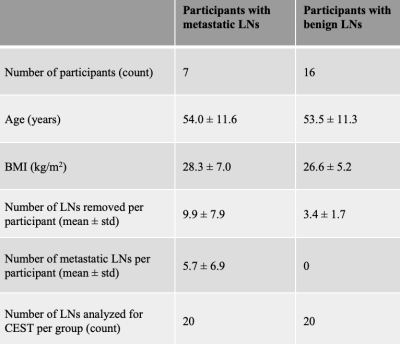

A total of 40 axillary LNs were identified from 16 participants with benign and 7 participants with metastatic LNs (20 LNs from each cohort were used for hypothesis testing to maintain identical comparator sample sizes) (Table 1). Participant groups were matched for age (metastatic: 54.0±11.6 years; benign: 53.5±11.3 years), body-mass-index (metastatic: 28.3±7.0; benign: 26.6±5.2 kg/m2), and race/ethnicity (white/non-Hispanic: all). More LNs were removed during surgery in the metastatic (9.9±7.9) vs. benign (3.4±1.7) cohort (p<0.01), as expected.Mean z-spectra and corresponding significant differences in cohorts with metastatic vs. benign LNs were observed in regions of known chemical exchange for the nuclear Overhauser effect (NOE) (-1.6 to -1.9 ppm PTR=0.087 vs. 0.051, p=0.04), hydroxyl (+0.5 to +1.5 ppm PTR=0.272 vs. 0.212, p=0.003), and amine (+2.3 to +2.6 ppm PTR=0.081 vs. 0.033, p=0.003) protons (Figure 2, Table 2).

Discussion

The quantified mean CEST z-spectra in axillary LNs of participants with biopsy-confirmed LN carcinoma indicate a unique LN tissue microenvironment detectable by CEST-Dixon MRI. Enhanced hydroxyl exchange is consistent with tumor-associated acidification of interstitial fluid, especially for aggressive breast cancer tumors (9, 12). In the rNOE range, enhanced and broadened CEST z-spectra in LN tissue composition in patients with metastasis were observed, indicating changes in molecular structures and possibly cellular membrane composition within the LN microenvironment (13). Noninvasive CEST MRI of metastatic and benign axillary LNs was demonstrated in this proof-of-principle study that could lead to further clinical trials evaluating imaging strategies for breast cancer metastasis that not only enhance sensitivity for prognosis based on axillary LN profiles, but also reduce the risk for secondary lymphedema if imaging can alleviate invasive biopsy procedures.Conclusions

Metastatic vs. benign LNs may exhibit unique CEST MRI contrast relevant to multiple labile proton regimes; as such, CEST MRI may have relevance for pre-surgical LN breast cancer staging and for guiding LN sparing resections to reduce risk for lymphedema.Acknowledgements

This research was funded by NIH/NINR 1R01NR015079, and NIH/NHLBI 1R01HL155523. Imaging experiments were performed in the Vanderbilt Human Imaging Core using research resources supported by the NIH grant 1S10OD021771-01. Recruitment through www.ResearchMatch.org and services at the Clinical Research Center are supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) Clinical Translational Science Award (CTSA) Program, award number 5UL1TR002243-03. REDCap resources were provided by NCATS/NIH UL1 TR000445. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.References

- DiSipio T, et al. Incidence of unilateral arm lymphoedema after breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Oncology 2013;14(6):500-515.

- Jiang S, et al. Applications of chemical exchange saturation transfer magnetic resonance imaging in identifying genetic markers in gliomas. NMR Biomed. 2022; Mar 16:e4731. doi: 10.1002/nbm.4731. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35297117.

- Cai K, et al. CEST signal at 2ppm (CEST@2ppm) from Z-spectral fitting correlates with creatine distribution in brain tumor. NMR Biomed. 2015 Jan;28(1):1-8. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3216. Epub 2014 Oct 8. PMID: 25295758; PMCID: PMC4257884.

- Chan KW, et al. CEST-MRI detects metabolite levels altered by breast cancer cell aggressiveness and chemotherapy response. NMR Biomed. 2016 Jun;29(6):806-16. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3526. Epub 2016 Apr 21. PMID: 27100284; PMCID: PMC4873340.

- Yin Wu, et al. Fast and equilibrium CEST imaging of brain tumor patients at 3T. NeuroImage: Clinical 2022; Vol. 33, 102890; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2021.102890

- Chen LQ, Pagel MD. Evaluating pH in the Extracellular Tumor Microenvironment Using CEST MRI and Other Imaging Methods. Advances in radiology 2015;2015:1-25.

- Crescenzi R, et al. CEST MRI quantification procedures for breast cancer treatment-related lymphedema therapy evaluation. Magn Reson Med 2020;83(5):1760-1773.

- Donahue MJ, et al. Assessment of lymphatic impairment and interstitial protein accumulation in patients with breast cancer treatment-related lymphedema using CEST MRI. Magn Reson Med 2016;75(1):345-355.

- Zhang S, et al. CEST-Dixon for human breast lesion characterization at 3 T: A preliminary study. Magn Reson Med 2018;80(3):895-903.

- Veronesi U, et al. Sentinel-lymph-node biopsy as a staging procedure in breast cancer: update of a randomised controlled study. Lancet Oncol 2006;7(12):983-990.

- Farrus B, et al. Incidence of internal mammary node metastases after a sentinel lymph node technique in breast cancer and its implication in the radiotherapy plan. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2004;60(3):715-721.

- Anemone A, Consolino L, Conti L, et al. Tumour acidosis evaluated in vivo by MRI-CEST pH imaging reveals breast cancer metastatic potential. British journal of cancer 2021;124(1):207-216.

- Zhou Y, Bie C, van Zijl PCM, Yadav NN. The relayed nuclear Overhauser effect in magnetization transfer and chemical exchange saturation transfer MRI. NMR Biomed. 2022 May 31:e4778. doi: 10.1002/nbm.4778. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35642102.

Figures

Figure 1. Participants undergoing axillary lymph node (LN) biopsy or dissection as part of breast cancer therapy were imaged before LN removal. The noninvasive MRI exam consisted of (A) diffusion-weighted imaging with background suppression (DWIBS) for axillary LN localization, (B) high spatial-resolution 3D T1-weighted imaging of (C) axillary LN anatomy, and (D) CEST imaging. LNs were identified and segmented on the non-saturated CEST equilibrium images (arrows and segmentation masks displayed for individual axillary lymph nodes).

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of participants identified to have metastatic or benign axillary lymph nodes confirmed by standard-of-care pathology reporting during breast cancer therapy.

Figure 2. The mean CEST MRI z-spectrum in LNs from patients with benign vs. metastatic LNs. The z-spectrum signal difference is plotted at saturation frequency offsets where a significant effect was measured. Enhanced hydroxyl, amine, and NOE CEST effects were observed in lymph nodes from patients with biopsy-confirmed metastatic breast cancer.

Table 2. Mean z-spectra and corresponding significant differences in cohorts with metastatic vs. benign lymph nodes (LNs). PTR=proton transfer ratio. *Student’s t-test significance criteria, two-sided p<0.05.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/0188