0182

Quantitative Perfusion with Rate-Pressure Product Corrections in Heart Transplant Patients with Cardiac Allograft Vasculopathy

Jay Bharatsingh Bisen1, Sandra Quinn1, Ozden Kilinc1, Havisha Pedamallu1, Kelvin Chow2,3, Rachel Davids2,3, Daniel C Lee4, Daniel Kim1, Richard L Weinberg4, James Carr1, Michael Markl1, Bradley D Allen1, and Ryan Avery1

1Radiology, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL, United States, 2Radiology, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, United States, 3Siemens Healthcare, Chicago, IL, United States, 4Cardiology, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL, United States

1Radiology, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL, United States, 2Radiology, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, United States, 3Siemens Healthcare, Chicago, IL, United States, 4Cardiology, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Vessels, Quantitative Imaging, Quantitative Perfusion, Heart Transplant, Coronary Allograph Vasculopathy

Cardiac Allograft Vasculopathy (CAV) is a form of accelerated intimal hyperplasia in heart transplant patients that limits long-term survival. Quantitative perfusion is a novel MR imaging technique that is useful in determining myocardial blood flow (MBF) and myocardial perfusion reserve (MPR) in CAV patients. After Rate-Pressure Product MBF corrections, Quantitative perfusion has shown that vessels with severe CAV (>70% stenosis) have significantly decreased MPR driven primarily by increased resting MBF. Quantitative perfusion may improve non-invasive monitoring of CAV status in heart transplant patients.Introduction

Cardiac Allograft Vasculopathy (CAV) is a form of accelerated intimal hyperplasia that limits long-term survival in heart transplant patients1. Improved noninvasive techniques are needed for early-stage CAV surveillance to guide treatment. Quantitative perfusion is an emerging CMR technique to characterize obstructive coronary disease and microvascular dysfunction2. Quantitative perfusion acquires a low-resolution arterial input function and higher-resolution tissue function images to quantify voxel-wise myocardial blood flow (MBF) at stress and rest, which can be used to calculate myocardial perfusion reserve (MPR)3-5. We hypothesize that differences in stress and rest MBF and MPR will predict CAV severity in heart transplant patients6.Methods

Ten patients who underwent the same Quantitative perfusion CMR with the same pulse sequence were retrospectively analyzed (46 ± 17 years; 60% male) to assess differences between CAV-positive (CAV+) and CAV-negative (CAV-) patients. For comparison of global values with CAV status, CAV+ was defined as moderate or severe CAV, whereas CAV- was defined as no or mild CAV. Grading of CAV was according to ISHLT criteria using corresponding invasive coronary angiography, right heart catheterization, echocardiographic and clinical data7. For individual epicardial artery and associated myocardial territory analysis, vessels were grouped into those with angiographic evidence of flow-limiting disease (>70% stenosis) in major vessels or associated branches, and without (<50% stenosis). No major vessels or associated branches included in this study had stenosis that was between 50% stenosis and 70% stenosis.Five CAV+ subjects were matched to CAV- subjects based on age, gender, time between transplant and scan, and age at transplant. Quantitative perfusion imaging was performed using a prototype dual-sequence acquisition with inline quantification3 on a 1.5T system (MAGNETOM Avanto, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) at rest and during 140 μg/kg/min of adenosine stress.

The data obtained from the inline Quantitative perfusion software3 was re-contoured and analyzed by the same observer (cvi42, Calgary) to attain global, LAD, LCx, and RCA MBF at rest and stress as well as MPR values. Comparisons were made 1) between CAV+/- patients and 2) between regions corresponding to vascular territories with stenosis >70% (n=8) and <50% stenosis vessels (n=22). Statistical comparisons were performed using independent t-tests.

After initial analysis, the derived MBF data was corrected using the Rate Pressure Product (RPP) calculated using the Systolic Blood Pressure (SBP) and Heart Rate (HR) during rest and stress of each imaging sequence. The following corrections8 were performed:

$$RPP=SBP*HR$$

$$MBFcorrected=(MBForiginal*10,000)/(RPP)$$

The corrected MBF values were used in subsequent analyses where independent t-tests were performed to compare CAV+/- patients and regions corresponding to vessels with stenosis >70% and <50% stenosis vessels, as before.

Results

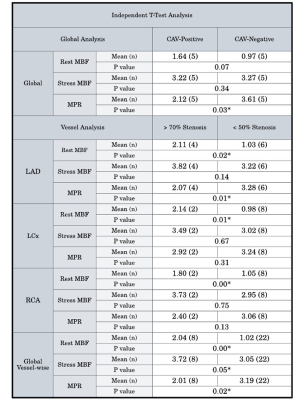

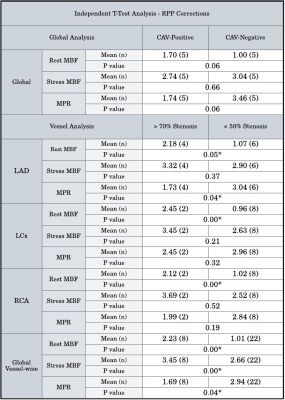

CAV+ patients presented with lower global MPR values than CAV- patients (2.12 vs 3.61 mL/g/min respectively, p=0.03) (Figure 1). This finding was consistent with lower MPR values in >70% stenosis vessels in comparison to <50% stenosis vessels (2.01 vs 3.19 mL/g/min, p=0.02). Territories with epicardial artery stenosis >70% also had both higher rest MBF (2.04 vs 1.02 mL/g/min, p=0.00) and stress MBF (3.72 vs 3.05 mL/g/min, p=0.05) compared with those without significant stenosis.After RPP corrections were performed, CAV+ patients did not show significantly higher resting MBF and decreased MPR in comparison to the analysis prior to correction. However, there were lower MPR values (1.69 vs 2.94 mL/g/min, p=0.04), higher rest MBF (2.23 vs 1.01 mL/g/min, p=0.00), and higher stress MBF (3.45 vs 2.66 mL/g/min, p=0.00) in territories with epicardial artery stenosis >70% compared with those without significant stenosis (Figure 2).

Conclusions

Quantitative perfusion is a promising approach for myocardial characterization in heart transplant patients at risk of CAV. Significant reductions in myocardial flow related to CAV were observed, with reductions in global and regional MPR that seem to be driven primarily by an increase in resting MBF. Further study with a larger cohort is needed to assess the clinical role of Quantitative perfusion for cardiac transplant patients, to explore correlations between abnormal MPR and CAV severity, and to correlate with other imaging modalities.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

- Finegold, JA., Asaria, P., & Francis, DP. Mortality from ischaemic heart disease by country, region, and age: statistics from World Health Organisation and United Nations. International journal of cardiology, 2013; 168(2), 934-945. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.10.0462.

- Knott, KD., Seraphim, A., Augusto, JB., Xue, H., Chacko, L., Aung, N., et al. The Prognostic Significance of Quantitative Myocardial Perfusion: An Artificial Intelligence-Based Approach Using Perfusion Mapping. Circulation, 2020; 141(16), 1282-1291. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.0446663.

- Kellman, P., Hansen, MS., Nielles-Vallespin, S., Nickander, J., Themudo, R., Ugander, M. et al. Myocardial perfusion cardiovascular magnetic resonance: optimized dual sequence and reconstruction for quantification. Journal of cardiovascular magnetic resonance : Official journal of the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, 2017; 19(1), 43. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12968-017-0355-54.

- Dandekar, VK., Bauml, MA., Ertel, AW., Dickens, C., Gonzalez, RC., & Farzaneh-Far, A. Assessment of global myocardial perfusion reserve using cardiovascular magnetic resonance of coronary sinus flow at 3 Tesla. Journal of cardiovascular magnetic resonance : official journal of the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, 2014; 16(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.1186/1532-429X-16-245.

- Dewey, M., Siebes, M., Kachelrieß, M., Kofoed, KF., Maurovich-Horvat, P., Nikolaou, K. et al. Quantitative Cardiac Imaging Study Group. Clinical quantitative cardiac imaging for the assessment of myocardial ischemia. Nature reviews. Cardiology, 2020; 17(7), 427-450. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-020-0341-86.

- Greenwood, JP., Maredia, N., Younger, JF., Brown, JM., Nixon, J., Everett, C. C. et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance and single-photon emission computed tomography for diagnosis of coronary heart disease (CE-MARC): a prospective trial. Lancet (London, England), 2012; 379(9814), 453-460. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61335-47.

- Mehra, Mandeep R., et al. “International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation Working Formulation of a Standardized Nomenclature for Cardiac Allograft Vasculopathy—2010.” The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation, vol. 29, no. 7, 2010, pp. 717–727., https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healun.2010.05.017.

- Shrestha, Uttam M., et al. “Assessment of Late-Term Progression of Cardiac Allograft Vasculopathy in Patients with Orthotopic Heart Transplantation Using Quantitative Cardiac 82rb Pet.” The International Journal of Cardiovascular Imaging, vol. 37, no. 4, 2020, pp. 1461–1472., https://doi.org/10.1007/s10554-020-02086-y.

Figures

Figure 1: Analysis of global resting MBF, stress MBF, and MPR between CAV+, CAV- patients, with sub-analysis of epicardial arteries and associated myocardial territories.

Figure 2: Analysis of global resting MBF, stress MBF, and MPR between CAV+, CAV- patients, with sub-analysis of epicardial arteries and associated myocardial territories after RPP MBF corrections.

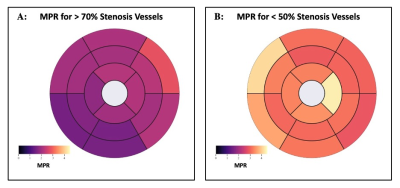

Figure 3: Bullseye plot comparing vessel-wise MPR averages in AHA segments for >70% stenosis patients (A) and <50% stenosis patients (B).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/0182