0181

Respiratory navigated free-breathing myocardial arterial spin labeling (ASL) with phase sensitive reconstruction1Heidelberg University, Mannheim, Germany, 2Delft University of Technology, Delft, Netherlands, 3University Aix-Marseille, Marseille, France

Synopsis

Keywords: Myocardium, Arterial spin labelling

Myocardial arterial spin labeling (myoASL) holds promise for needle-free myocardial blood flow (MBF) quantification but requires tedious averaging over multiple breath-holds. Here, free-breathing myoASL was implemented with dual-navigator gating, both with bSSFP and spoiled GRE readout. Images were processed using individual blood T1 and inversion time correction as well as a phase-sensitive (PS) image reconstruction. Phantom results showed PS reconstruction to reduce MBF variations for short RR and T1 values. Perfusion values were comparable with breath-held myoASL and on par with the literature. Ultimately, this can enable faster myoASL acquisitions with improved patient comfort.Introduction

First-pass perfusion imaging is the clinical gold standard for detecting myocardial ischemia and quantifying myocardial perfusion1. However, it requires the use of exogenous contrast agents limiting its repeated use. Arterial spin labelling (ASL) can provide a promising alternative based on magnetically labeled blood as endogenous tracer. Due to low signal-to-noise ratios and high physiological noise levels2, however, multiple averages are needed to ensure sufficient accuracy. While myocardial ASL (myoASL) has mostly been performed during breath-holds2,3, free-breathing, retrospectively gated myoASL has recently been demonstrated4. However, retrospective image selection may lead to excessive scan times. In this work, we propose a respiratory navigated free-breathing myoASL sequence with increased scan time efficiency and noise performance, using phase-sensitive myoASL image reconstruction.FAIR-myoASL sequence

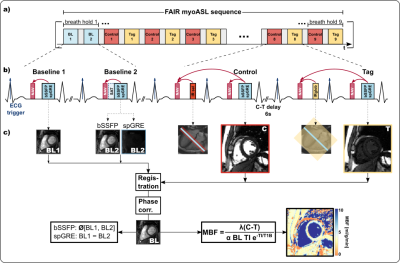

Imaging was performed on a 3T scanner (Vida, Siemens). For all measurements, a double ECG-gated Flow Alternating Inversion Recovery (FAIR) ASL sequence3 was implemented (Fig.1). For the free-breathing sequence, as shown in Fig. 1, a pencil-beam navigator placed at the liver dome was played prior to both inversion and image acquisitions. To ensure that images are acquired only upon successful inversion, FAIR images were accepted only when both consecutive navigators were valid. This dual-heartbeat navigation also led to matching slice-selective inversion and excitation in control images. Baseline images were conventionally navigated within a single heartbeat.Phantom and In vivo Measurements

Data was acquired both with bSSFP and spoiled GRE (spGRE) readout. In phantom, two control-tag image pairs were acquired with a 6s delay between the two images. Phantom experiments were performed with varying simulated RR intervals in a NiCl2-doped agarose phantom. In vivo images of 4 healthy subjects (1 female, 3 male, 35±4.8 years) were obtained in 12-15s long breath-holds per image pair depending on the heart rate (scan duration ~3min) as well as in free-breathing (scan duration ~2-3 min). For each of the four combinations of readout and breathing strategy, eight control-tag pairs were acquired with a 6s delay. In phantom and in vivo, two baseline images (no inversion) were acquired with bSSFP, while with spGRE one of the two was directly preceded by a WET saturation pulse (“saturated baseline”, Sat-BL) to compensate for the effect of the imaging readout5,6. All images were acquired with 1.6x1.6x8mm3 voxel size, TE 1.36/1.97ms, TR 3.6/4.3ms, and FA 60°/17° (bSSFP/spGRE), GRAPPA 2 and Partial Fourier (6/8). MOLLI7 was used for T1 mapping in phantom and in vivo.Data analysis

In vivo image pairs with inconsistent inversion times (TI) were excluded, before registering the images groupwise8. Phase-sensitive (PS) reconstruction was performed to restore the signal polarity and image contrast. To this end, the phase difference was unwrapped and rounded to 0 or π to extract the signal polarity9. Pixel- and segment-wise myocardial blood flow (MBF) were reconstructed using individual blood T1 and a Sat-BL correction as previously described5,6,10.Results

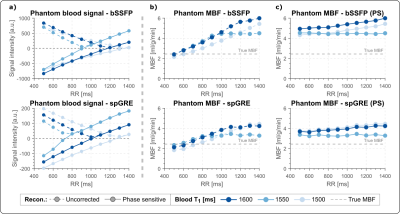

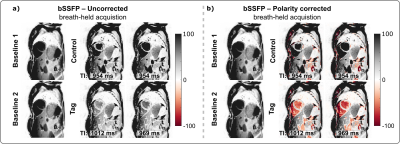

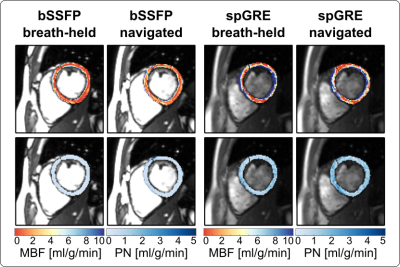

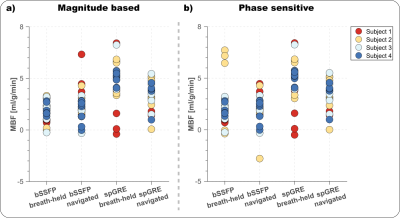

Phantom MBF values are underestimated and vary with the RR duration, when no signal polarity correction is used (Fig. 2b). The inflection point occurs at longer RR intervals/TIs for longer T1 values and, also for spGRE compared to bSSFP. With PS reconstruction the phantom MBF is largely constant over the range of simulated heart rates. The effect of the polarity correction on in vivo data is shown in Fig. 3. for one representative subject with bSSFP readout. The bright blood pool signal in the uncorrected images (Fig. 3a) indicates that the readout occurred before the inflection point of the blood signal due to a high heart rate (short RR duration and TI). The polarity corrected (Fig. 3b) images show a dark blood pool and restored image contrast. In vivo MBF maps show visually homogeneous values throughout the myocardium, with comparable physiological noise between bSSFP and spGRE (Fig. 4). Mean septal MBF per subject ranged between 1.25/2.53 and 3.48/5.70 ml/g/min (bSSFP/spGRE, Fig. 5), with a reduced number of outliers using phase-sensitive reconstruction in some subjects.Discussion

In this work we evaluate a free-breathing myocardial ASL sequence, using navigator gating and phase-sensitive reconstruction. Homogeneous MBF map quality is achieved during free-breathing. Phase-sensitive reconstruction is shown to reduce the number of outliers in some subjects. As a result of short RR intervals, i.e. short TIs, the magnetization can be negative at the time of the image readout depending on the tissue T1. The distorted image contrast can then lead to inaccurate MBF quantification. Phase-sensitive reconstructions were shown to mitigate this effect in phantom. A residual phantom MBF deviation was observed due to the impact of the image readout. Phantom as well as in vivo MBF matched previously reported perfusion values2,3,4. Respiratory navigation generally yielded shorter scan times than breath-held acquisitions, while MBF maps were comparable for the two breathing strategies. Our in vivo data further suggest that the use of phase-sensitive reconstruction may reduce the number of outliers obtained during the MBF measurement.Conclusions

Phase-sensitive perfusion reconstruction restores image contrast and may result in more precise MBF values. Free-breathing myoASL was demonstrated with dual-respiratory navigation and double ECG-gating and yields perfusion values comparable to breath-held myoASL. This approach can enable faster contrast-agent free perfusion mapping with improved patient comfort.Acknowledgements

M.B.I. acknowledges is funded by a PhD scholarship from the Landesgraduiertenförderung Baden-Württemberg, and a Procope Mobility stipend. S.W. acknowledges funding from the 4TU Precision Medicine program, an NWO Start-up STU.019.024, and ZonMW OffRoad 04510011910073.References

1. Gerber, B. L., Raman, S. V., Nayak, K., Epstein, F. H., Ferreira, P., Axel, L., & Kraitchman, D. L. (2008). Myocardial first-pass perfusion cardiovascular magnetic resonance: history, theory, and current state of the art. Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, 10(1), 1-18.

2. Zun, Z., Wong, E. C., & Nayak, K. S. (2009). Assessment of myocardial blood flow (MBF) in humans using arterial spin labeling (ASL): feasibility and noise analysis. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine: An Official Journal of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 62(4), 975-983.

3. Do, H. P., Jao, T. R., & Nayak, K. S. (2014). Myocardial arterial spin labeling perfusion imaging with improved sensitivity. Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, 16(1), 1-6.

4. Aramendía‐Vidaurreta, V., Gordaliza, P. M., Vidorreta, M., Echeverría‐Chasco, R., Bastarrika, G., Muñoz‐Barrutia, A., & Fernández‐Seara, M. A. (2022). Reduction of motion effects in myocardial arterial spin labeling. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 87(3), 1261-1275.

5. Božić-Iven, M., Rapacchi, S., Pierce, I., Thornton, G., Tao, Q., Schad, L. R., Treibel, T., & Weingärtner, S. (2022). Towards reproducible Arterial Spin Labelling in the myocardium: Impact of blood T1 time and imaging readout parameters. Proceedings of the Joint Annual Meeting ISMRM-ESMRMB.

6. Božić-Iven, M., Rapacchi, S., Pierce, I., Thornton, G., Tao, Q., Schad, L. R., Treibel, T., & Weingärtner, S. (2022). Improving reproducibility of cardiac ASL using T1 and flip angle corrected reconstruction. Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the SMRA.

7. Messroghli, D. R., Radjenovic, A., Kozerke, S., Higgins, D. M., Sivananthan, M. U., & Ridgway, J. P. (2004). Modified Look‐Locker inversion recovery (MOLLI) for high‐resolution T1 mapping of the heart. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine: An Official Journal of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 52(1), 141-146.

8. Tao, Q., van der Tol, P., Berendsen, F. F., Paiman, E. H., Lamb, H. J., & Van Der Geest, R. J. (2018). Robust motion correction for myocardial T1 and extracellular volume mapping by principle component analysis‐based groupwise image registration. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 47(5), 1397-1405.

9. Gowland, P. A., & Leach, M. O. (1991). A simple method for the restoration of signal polarity in multi‐image inversion recovery sequences for measuring T1. Magnetic resonance in medicine, 18(1), 224-231.

10. Buxton, R. B., Frank, L. R., Wong, E. C., Siewert, B., Warach, S.,

& Edelman, R. R. (1998). A general kinetic model for quantitative perfusion

imaging with arterial spin labeling. Magnetic resonance in medicine, 40(3), 383-396.

Figures